Virtue ethics

What makes something right or wrong?

One of the oldest ways of answering this question comes from the Ancient Greeks. They defined good actions as ones that reveal us to be of excellent character.

What matters is whether our choices display virtues like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. Importantly, virtue ethics also holds that our actions shape our character. The more times we choose to be honest, the more likely we are to be honest in future situations – and when the stakes are high.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Deontology

What makes something right or wrong?

One answer comes from the work of German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who is considered the founder of an ethical theory called deontology. Deontology comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. It holds, quite simply, that actions are good or bad based on whether they fulfil universal moral duties.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

WATCH

Relationships

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Consequentialism

For lots of people, what makes a decision right or wrong depends on the outcome of that decision.

Does it increase or decrease the amount of happiness in the world? This kind of thinking is typical of consequentialism: an ethical school of thought that says what makes an action good or bad is, you guessed it, the consequences.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

An ethics framework is a statement of an organisation’s purpose, values and principles.

It makes clear what they believe in and what standards they’ll uphold. It’s a roadmap to good decision making and, if it’s lived throughout the organisation. It’s also a guide to making an organisation the best version of itself.

Trying to make a decision without knowing your purpose, values and principles, is like being at sea without a rudder. They’ll be pushed around by the winds of our desires, mood, unconscious mind, group dynamics and social norms. The choices they make won’t really be their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: Should I tell my student’s parents what they’ve been confiding in me?

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Socrates

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What is ethics?

Ethics asks how we should live, what choices we should make and what makes our lives worth living.

It helps us define the conditions of a good choice and then figure out which of all the options available to us is the best one. Ethics is the process of questioning, discovering and defending our values, principles and purpose. It’s about finding out who we are and staying true to that in the face of temptations, challenges and uncertainty. It’s not always fun and it’s hardly ever easy, but if we commit to it, we set ourselves up to make decisions we can stand by, building a life that’s truly our own and a future we want to be a part of.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: Should I tell my student’s parents what they’ve been confiding in me?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

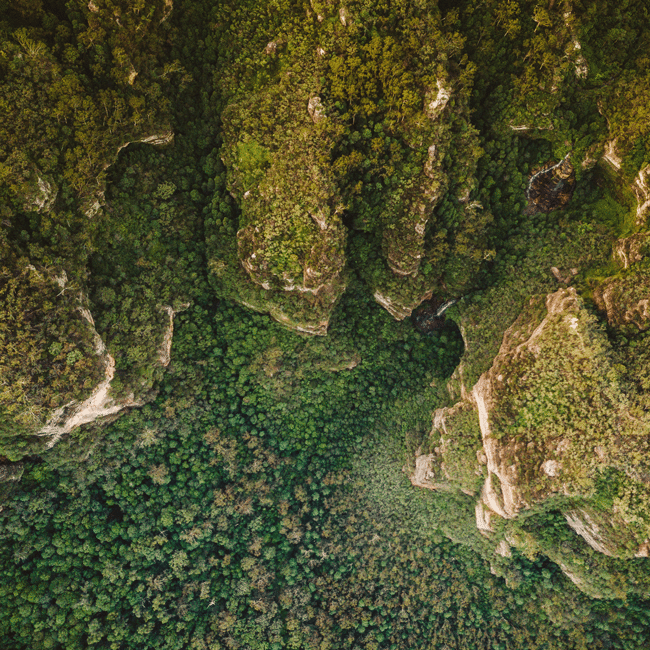

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Dr Chloe Watfern Dr Priya Vaughan 30 OCT 2023

As part of their 2023 Ethics Centre residency, researchers Dr Chloe Watfern and Dr Priya Vaughan collaborated with researchers, artists and service providers to explore creative approaches to climate distress, and the ethics of care for place, self, and community in the context of ecological crisis.

Why is it that we are touched most by the things closest to us? Touched, as in, made to feel something strongly, to care in its meanings as both a verb and a noun – to feel concern for and to want to protect or nurture a child, a parent, a special place, a garden, or the bird out the window. It’s a question with an obvious answer. Because they are close. Because they can be felt, sometimes even touched.

Traditional moral theories require us to be unemotional, rational, and logical. For example, we are thought (or urged) to objectively calculate the extent to which our actions will lead to a good outcome for the greatest number of people. However, in the context of our daily lives, an ethics of care highlights the pull of relationships and feelings, like love and compassion, in our moral decision-making.

Tentacle, n.

Zoology: A slender flexible process in animals, esp. invertebrates, serving as an organ of touch or feeling. (Oxford English Dictionary)

The first recorded use of the word “tentacle” in the English language was in 1764, when A. P. Du Pont wrote that “the fingers, or tentacles, end in a deep blue.”

At about this time, the industrial revolution was just beginning in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States. Humans in these places gradually, and then very rapidly, moved away from producing things by hand. Coal, iron and water were the core elements of this rapid transformation in societies, extraction and exploitation its drivers. Today, we are at the coal face of its legacy.

Where will all this lead? To a deep blue? To a burning world? To unaddressable environmental collapse? To rubble, ash, and mud?

Care in an era of climate distress

Certainly, we know and feel that the living systems of the earth have been deeply compromised by human activities. This knowledge is a source of intense distress for many of us. At the same time, the collapse of systems creates new and ancient forms of distress, as homes and lives are destroyed or radically altered.

More and more of us care as more and more of us are touched by the effects of our collective actions: biodiversity loss, pollution, global boiling. What might we do with our bare hands, our sentient bodies, to make up for all the loss on our horizon? And where is the horizon anyway?

Professor Timothy Morton refers to global warming, like evolution, or relativity, as a “hyperobject”: something that is very difficult to comprehend using the cognitive tools that we humans have evolved to possess. Climate is everywhere and nowhere, in Antarctic ice sheets and cow belches, in bees and babies, in the cloud and the web, in bushfire smoke and too much (or not enough) rain on a tin roof.

Does Earth’s climate care that it is boiling? We don’t know, because we don’t know how to ask. We can only guess.

Stories of care

During our residency at the Ethics Centre in May 2023, we asked humans to share their stories of care. Colleagues, friends, family members, clinicians, artists, researchers, elders, and knowledge keepers each brought an object that connected to community, self, or planetary care in the climate crisis. These objects – a clay pot, a biodegradable bin bag, leaves collected on country, a handful of seeds – held and evoked memories of grief and loss, but above all, connection with humans, more-than-humans, and places. Close encounters filled with care.

Seeking a way to capture and share these memories, we asked these humans to help us create a tentacular creature: part cephalopod, part bird, part plant, part insect, part fungi, part human, part bacteria, part virus, part landscape.

For us, this tentacular creation was the perfect creature to hold stories of care, responsibility, hope, and fear in the context of our precarious and precious world.

Neither and both human and animal, nature and artifice, Tentacular collapses fictious binaries that have, historically, enabled the climate crisis to be seen as a problem with ‘nature’, rather than the total phenomenon it is.

Each tentacle of this collective artwork reaches outwards, seeking connection and offering stories that speak to the ways we might care, in responsible and responsive ways, for ourselves, each other, and the wounded world. Here, we share some evocative snippets from the stories of care that each person offered:

Gadigal, Bidjigal and Yuin elder Aunty Rhonda Dixon–Grovenor grew up being taught to respect and care for country. She tells people “If we are in nature and enjoy it and care for it, then it nourishes us… Care is a relationship, it’s a two-way, it’s not just one person dominating.”

“Care is a relationship, it’s a two-way, it’s not just one person dominating.” – Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor

Academic Dr Barbara Doran reflects on the tuition of a beehive: “The bees connected me to a more nuanced relationship with nature… Now, I’m more aware of rain, of flowering patterns, of birds: the ecosystem is amplified in my eyes. But after the fires, I’ve noticed an echo-effect. They have been splitting more than they usually do. This year is the first season with no honey. I’m noticing these resonant patterns in a climate changed world. The hive is my teacher, healer and sharpener of antennas.”

Psychotherapist and Group Facilitator at We Al-li, Georgie Igoe asks us to consider threshold experiences: “For me, care means sitting with discomfort and uncertainty, opening ourselves up to the unknown – in the muck, in the grief, not sidestepping it but acknowledging its power.”

Installation artist and theatre-maker Brownyn Vaughan shares the wisdom of her favourite writers and of her favourite swimming place: “The Mahon pool brought me up, it’s my go-to-place… Professor Astrida Neimanis tells us we must stop trying to ascend and transform. Instead, we must submerge, become part of the water.”

Artist-survivor, and lived experience advocate, Lea Richards, mourns and advocates for the mountains: “Snow melt is mountain’s blood. I weep for the glaciers, so far from arid Australia, yet not separate. I imagine connections to those vanishing snows– a flow of water between us. If I conserve this precious blood, can I tend those far places, postpone the melting?”

Embedded in many, perhaps all, of these stories is a conviction that we need to, as Bronwyn said, submerge, to acknowledge our place in the meshwork of the world, and in so doing, to learn with and from the environment. This means burying ego, rejecting a hierarchy where humans are at the apex, and attending in quotidian ways to what is happening to us and around us. Let’s become like tentacles, feeling our way into a better relationship with the world we care so much about.

Tentacular, as part of the exhibition: Care is a Relationship is on display at UNSW Library until 17 November, 2023.

Find out more about The Ethics Centre Residency Program.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Stopping domestic violence means rethinking masculinity

BY Dr Chloe Watfern

Dr Chloe Watfern works across the social sciences, humanities, and creative arts to tackle the big and interconnected challenges of our time, from social inclusion and mental health to climate change. She is currently working at Black Dog Institute (UNSW) and Maridulu Budyari Gumal SPHERE (Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise)’s Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform.

BY Dr Priya Vaughan

Dr Priya Vaughan takes an interdisciplinary, and participatory approach to health research, utilising arts-based and socially informed methodologies, knowledge translation (KT) strategies, and interventions to learn about and support mental health and wellbeing. She is currently working at Black Dog Institute (UNSW) and Maridulu Budyari Gumal SPHERE (Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise)’s Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform.

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 18 OCT 2023

Hijack, the new Idris Elba-starring miniseries, opens with every airline passenger’s nightmare – a bullet, found in the bathroom of a plane. Within moments, things go from bad to worse.

The ragtag group of heroes, a collection of passengers led by Sam Nelson (Elba), a corporate business negotiator, find themselves in the middle of a hijacking plot, surrounded by criminals, and unable to get help from those down on the ground who, we quickly learn, are ensnared in the plot themselves.

Such a format is not necessarily new – television and film have been littered with stories of hostile airline takeovers, from the big brash action of Air Force One, to the real-world horror of United 93, a tragic retelling of the 9/11 attacks. But what sets Hijack apart is its rapidly escalating sense of dread. Time and time again, Sam and his fellow passengers are faced with impossible decisions, and time and time again, they are foiled. That opening nightmarish feel only deepens – you know those dreams where everything goes wrong; where you are powerless; where the adversaries keep mounting? That’s key to Hijack’s tone, a story of ever-escalating horrors, through which Sam must try to keep himself – and his ethical code – alive.

Indeed, this mounting sense of risk means that Hijack poses an interesting question about ethical deliberation under fire. Sam, who is well-versed in negotiation, but not well-versed in negotiation where the stakes are so high, must repeatedly make rapid-fire decisions. Does he send a text to his wife? Does Sam continue his attempted revolt after he discovers that the hijackers know who his family are, and will kill them if anything goes wrong? Does Sam rush the cockpit? And how responsible will he ethically be if he fails? How much blood is on his hands?

Decision making turned up to 11

The problem of ethical decision-making under fire is essentially the problem of the difference between theory and practice. Sit people down and ask them what the right thing to do is, give them time, don’t hurry them, and psychological studies show that they’ll have a better chance of choosing the ethical answer.

In a famous experiment known as The Good Samaritan, a group of priests-in-training were told to head across a university campus to deliver a speech on the importance of helping others. Some of these priests were given ample time to make it across the campus; others were told they had to rush. Along their trip, the experimenters planted a person in need – an actor, who feigned being sick, and asked for help. The majority of those priests who had been told they weren’t in a rush stopped to help. But the priests who had to move fast, and were stressed and distracted, largely ignored the actor – even though they were literally on their way to give a speech on how to care for their fellow human beings.

The experiment shows that the more that pressure increases – particularly time pressure – the less likely we are to do the right thing. Which poses a significant problem for ethical training. How can you fight against the forces of a chaotic world?

Philosopher Iris Murdoch was aware of the everyday pressures that we meet constantly. For that reason, she considered ethical training a process which prepares us to act unthinkingly. The more we make the right decisions when we do have time, the more likely we are to shape our instincts to be more ethical, and therefore act virtuously when we don’t have time. In this way, Murdoch collapses theory into practice, treating them not as divorced from one another, but with theory informing practice.

Which is a view that Hijack supports. Sam’s cushy day job has given him an unusual set of skills that he himself didn’t even realise that he had. All that work he conducted for years? It was training for this moment.

The ethics of risk

A related issue pertaining to theory and practice is the unknowability of the future. Thought experiments and ethical dilemmas conducted theoretically can have clear right or wrong answers, based on outcomes. But when we’re actually moving through the world, we’re blind to these outcomes. More often than not, we’re stumbling through the ethical world, making decisions based on the hope that things will work out, but never actually knowing if they will.

This is the ethics of risk, extensively covered by the philosopher Sven Ove Hansson. According to Hansson, “risk and uncertainty are such pervasive features of practical decision-making that it is difficult to find a decision in real life from which they are absent.”

Hansson’s solution to this problem is to consider “fair exchanges of risk.” He forgoes the idea that we will never be perfect moral creatures. Because the world is uncertain, we can only ever move towards good ethical actors. There’s no way that we can ever always do the right thing, and nor should we expect ourselves to. Instead, we must try. That is the important part.

So it goes in Hijack. Sam is a flawed main character, who frequently makes errors while trying to save those around him. But we, as audience members, forgive him for this. We don’t judge him for the plans that fail. We see his movement towards good behaviour, and that’s what matters.

In that way, we can also see theory and practice moved out of contention with each other. Theory is the goal; practice is the action. We’ll never live in a fully theoretic state. But what Hijack tells us, is in the face of that impossibility, we should not throw up our hands. We should instead keep moving towards theory – a spot on the horizon that is forever escaping us, but that we never stop chasing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

The Yes campaign is failing. If nothing changes soon, then October 14 will see constitutional reform fail, setting back recognition and reconciliation by years, if not decades.

And no amount of impassioned speeches by politicians, mass rallies by the Yes faithful, uplifting advertisements or – dare I say – editorial columns are likely to shift the needle towards Yes.

This is because voters who are currently unsure or leaning towards No have tuned out the “official” platforms. Their trust in mainstream media outlets has collapsed to single digit figures. It’s not even that they’ve switched to social media. It turns out that the only ones who have their ear are friends, family and colleagues. In this age of mass cynicism and social media schisms, it’s good old-fashioned relationships that still matter.

So, if you believe in the Voice, as I do, if you believe it represents an opportunity for Australia to take meaningful steps towards reconciliation with First Nations peoples, and if you believe it could be a stepping stone to a more unified Australia that each of us can be proud of, then your time to act is now.

But how? The key is to leverage the power of relationships and dive into conversations with your friends and relatives, especially people over the age of 55, who are currently the most likely to vote No. That’s your parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, or if you’re in that age group yourself, your childhood friends or neighbours.

If the prospect of starting a “political” conversation with family members fills you with dread, that’s understandable. These conversations often succumb to pitfalls that only increase animosity and polarisation. But get them right and they can be transformational. If you’re brave enough to strike up a conversation over the dinner table, here’s how to do so constructively. In fact, these tips can help you have better conversations regardless of how you intend to vote.

First: show respect. It’s all too easy (and, in some circles, encouraged) to believe that those who disagree with us must be either stupid or malicious. Sometimes they are. But signalling disrespect is a surefire way to kill any possibility of persuasion. Even the faintest whiff of disrespect triggers defensiveness, and when that happens, constructive conversation is over.

One way to show respect is to hold your tongue and listen – really listen. Often, people get belligerent because they don’t feel heard. That means two of the biggest tools in your arsenal are your ears. Just listening carefully, asking a few questions and repeating back a summary of what they have said can be transformative. It makes them feel heard and it gives you a fighting chance of understanding where they’re coming from.

Do this before you’ve shared your views. Our natural tendency when we hear someone say something we don’t agree with is to immediately open our mouths and tell them that we think differently. But this sets you at loggerheads from the outset. Instead, hold back. Hear them out and show you’re interested into getting to the bottom of the matter. That way it’s not a tug of war between the two of you but one where you’re on the same side pulling against ignorance.

While listening, you’re likely to hear them offer reasons to support their view. Some will be authentic, but many will be post-hoc rationalisations of deeper unstated motivations. You can spot a post-hoc rationalisation because when you show that it’s false, it doesn’t change their mind. That means it was never the real motivation for their beliefs, just a distraction.

The trick is not to challenge or fact check post-hoc rationalisations head-on but to change the way they perceive the issue in the first place. Once you’ve generated enough goodwill, offer an alternative perspective on the issue. You don’t need to encourage, let alone demand, they adopt your perspective, just offer it as your reason for voting the way you intend to.

You’re nearly done. If you’ve made it this far, you’ve done just about all anyone can do in a single conversation. Thank them and move on to something else. Let them mull over your perspective, and perhaps in the next conversation you might be able to go deeper. Minds rarely change in a single sitting.

Of course, there will be times when the conversation goes off the rails. Maybe your discipline cracks and you scoff at one of their remarks. Perhaps they refuse to engage in good faith. Maybe they just want to troll you to get a reaction. If any of these happen, back out. Focus instead on reinforcing the relationship based on other shared values – family, sport, food, whatever it is that brings you together – so perhaps in the next conversation they won’t feel the need to get defensive, or offensive.

Good conversations, particularly persuasive ones, take work. But it is possible to avoid the worst pitfalls and have a constructive discussion. If even a few unsure voters are swayed, it could shift the tide of the referendum. And given the Voice is about being heard, it’s rather fitting each of our voices could help make the difference.

An edited version of this article appears in The Sydney Morning Herald.

Image: AAP Image/Jono Searle

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How much should politics influence my dating decisions?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Plato

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 6 OCT 2023

Ethical dilemmas are, by their nature, uncomfortable or difficult to tackle, but they can also teach us a lot about our own values and principles and prepare us for an ethically complex world.

You’re about to take a major exam that will determine whether you get accepted into a potentially life-changing course. But you hear that there’s a leaked copy of the exam paper doing the rounds, and other students are studying it carefully. There are only a precious few spots available in your desired course, and if you don’t also sneak a peek at the leaked exam paper, you are likely to miss out. Should you cheat by looking at the leaked exam paper, given you know other students are doing the same?

How about if you found out that the company you work for was partnering with an overseas contractor known for running sweatshops and flouting labour laws, meanwhile your company’s branding is all about how ethical and sustainable it is. Would you speak out to management, or on social media, even if doing so might cost you your job and income?

If these scenarios give you pause, you’re not alone. Each represents a different kind of ethical dilemma we might come across, and by their nature they can be highly unsettling and difficult – if not impossible – to resolve in a way that satisfies everyone involved.

But what makes something an ethical dilemma? It’s important to note that an ethical dilemma is not a simple question of doing the ‘right’ thing or the ‘wrong’ thing, like whether you should lie to cover up for something bad that you did.

A genuine ethical dilemma arises when there is a clash between two values (i.e., what you think is good) or principles (i.e., the rules you follow). Or it can be a choice between two bad outcomes, like knowing that whatever you do, someone will get hurt.

That’s what makes them so uncomfortable; we feel like whatever choice we make will involve some kind of compromise.

All in the mind

One way to prepare yourself to face real-world ethical dilemmas is to strengthen your moral muscle by practicing on hypothetical scenarios – a staple of philosophy classes.

Consider this: you’re the captain of a sinking ship, and the lifeboat only has room for five passengers. Yet there are seven people aboard the ship, including yourself. Whom do you choose to board the lifeboat? The pregnant woman? The ageing brain surgeon? The fit young fisherman? The teenage twins? The reformed criminal who is now a priest? Yourself?

Or how about this: you’ve just started your shift as the only surgeon in a small but high-tech hospital. As you walk into your ward, you’re presented with five dying patients. You know nothing else about their personal details except that each is suffering from a different organ failure. Without assistance, all will die within 24 hours. However, at that moment, a healthy patient is wheeled in for an unrelated minor procedure. You also know nothing about their personal circumstances, but you do know they have five perfectly healthy organs. Were you to allow that patient to die (as they will without treatment) you know you could save the lives of the other five dying patients. Would you allow one to die to save five?

Each of these scenarios is carefully constructed to put pressure on your ethical intuitions and force you to make difficult decisions.

Tackling a hypothetical dilemma gives you an opportunity to reflect on your own values and principles, and search for good reasons to justify your choices.

Even if the hypothetical situation is absurdly unreal, you can still learn a lot about yourself and your ethical stance by considering how you would act in these cases.

Your first impulse might be to try and change the circumstances to eliminate or minimise the dilemma. We might speculate that we could squeeze another person on the lifeboat, or that the organ transplants may not succeed, and that might make our decisions easier. This is entirely natural – and sensible – especially because dilemmas in the real world are rarely as clear cut. But dodging the dilemma misses the point of the exercise.

You might decide that a consequentialist approach is the best one for the lifeboat scenario, causing you to pick the people who might end up leading the richest lives or having the most positive impact on others. But you might decide that a deontological approach is most appropriate for the surgeon’s dilemma, arguing that it’s inherently wrong to withhold treatment from an ‘innocent’ patient, even if it ends up saving lives.

It’s important to remember that hypothetical dilemmas like this are designed so that there’s likely no simple answer that will satisfy everybody. Even reasonable people can disagree about what course of action to take. That’s fine. The important bit is not really the answer you come to but the reasons you give to support it. That’s what ethics is all about: finding good reasons to act the way we do.

Most of us are likely to go through life without ever having to put people in lifeboats or contemplate the death of one to save five, but by testing ourselves with these dilemmas we can build our ethical muscles and be more ready to face other dilemmas that world could throw at us at any time.

If you’re struggling with a real-life ethical dilemma, it can be tough finding the best path forward. Ethi-call is a free independent helpline offering decision-making support from trained ethics counsellors. Book a call today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

When identity is used as a weapon

When people reduce an artist to one aspect of their identity, whether it be gender, ethnic or religious, it diminishes their humanity.

Identity is indelibly linked to our individual and collective places in the world. It is a marker, across many classifications, that creates distinctions that can help or harm us. But should it have such power? Is there any neutrality to how we create for public consumption, and if not, how can there be neutrality in how these are critiqued? Even with the cultural, social, sexual and other differences, surely there is acceptance that stories do – and should – have universal value?

A few years ago, Ruby penned an influential essay noting that, sometimes, white arts reviewers seemed unable or unwilling to see past ethnicity in literary criticism. In particular, there was an apparent tendency to take everything an Arab artist says literally, as if style, metaphor, flair and all the other features of literary penmanship were simply beyond our capabilities. It was not an objection to white reviewers critiquing the work of non-white artists. It was simply asking: “How do we respond when white reviewers can’t understand our work fairly enough to critique it?”

It was disheartening to see, some years later, the same issue rear its head, again in the pages of prestigious literary journals, again taking an Arab author to task by refusing to accept his work as fiction and insisting it must be thinly disguised autobiography. This time, however, the criticism was spearheaded by other Arabs.

Acclaimed Arab-Australian poet and novelist Omar Sakr was the subject of a bizarre string of connected critiques of his debut novel Son of Sin, two of which were written by Arabic speakers. What links these essays is not an issue with Sakr’s narrative style, plot structure, or characterisation but a fixation on his personal life and method of transliterating Arabic expressions, with the latter dismissed as too crude and incorrect to pass muster as ‘genuine’ Arab storytelling. His credibility diluted under the more ‘authentically Arab’ gaze of these two reviewers, Sakr’s Arabness was put into question.

It was extraordinary to witness such a coordinated attack on someone’s identity, only for identity itself to then be used to mask the attack. The implication being that as an artist, Sakr’s identity is fair game, but as his critics, theirs is beyond reproach.

As two Arab women who have both been critiqued extensively and who have critiqued the work of others, we are no strangers to writing and talking about these issues. We do not hide our Arab heritage, how this has informed our work, and how we are perceived and treated by wider society.

But what we have to offer is also of value to non-Arabs. Both of us have tried, over many years, to normalise rather than ‘otherise’ our experiences as a minority.

We believed that in being open about our identity – and the backlash we receive for it – we would eventually be able to transcend, not the identity itself, but the defining role it too often plays in our professional as well as personal lives. To make it a part of us but not all of us so that we may break down rather than reinforce the figurative walls that separate us.

Ruby’s portfolio of media work includes more than a decade of arts criticism, political analysis, and feature articles on everything from mental health to homelessness to pop culture. It is her work on race, however, that attracts the most attention and spurs the most backlash. Often, when critics accuse us of “making everything about race,” they are simply revealing their own tendency to see us only in racial terms. Our input on general societal matters considered irrelevant, we are simultaneously expected to have nothing more than our identity to offer and then berated for offering it on our own terms.

There is an endless thirst for stories that confirm the oppressed Arab woman archetype, only for this archetype to then be used against us. A workplace manager once told Amal that her “difficulty” with authority had something to do with her upbringing and the men in her life, while another taunted her about her perceived (lack of) sex life. Even as a journalist reporting for trade publications she was reduced to her identity – and found wanting.

Defying these forced identity markers, Amal went on to write several books that traverse universal themes, from the divine and spiritual belief, to ageing and how we live. Her novels explore connection, love and personal evolution, all centring Arab women raised in Australia but who remain connected to the homeland, primarily Palestine. But the stories are not about this. Navigating dual worlds; these characters acknowledge but are not defined by their heritage. It is their reality and normality. They do not exist to address stereotypes but as characters in their own right. They just are, without apology or reduction or explanation.

Still, media coverage of her work often reverts to stereotype, accompanied by images of women in headscarves or headlines about Amal’s faith. Every image, every headline, seemingly there to remind us that, even when our work subverts it, we cannot outrun that archetype.

We are more than decades of trauma and displacement. We are not conflict. Our dispossession is not the definition of who we are, and what we can achieve. But in a social climate of such gatekeeping as to which Sakr was subjected, can we ever simply be writers or does our ethnicity mean we can only be Arab-Muslim ones? Must we write merely to educate and inform, only to live in fear of being deemed not Arab enough, or can we be creative storytellers in our own right?

For all the discourse about identity and discrimination, including the much-needed influx of historically marginalised voices, it seems that there is an attachment, both from the dominant society and from within these marginalised groups to maintain the status quo. Reducing us to the barest, stereotypical elements of our racial heritage – whether or not we wear a headscarf; if we transliterate “uncle” correctly – we are refused an existence outside of its constraints.

It is hard not to conclude that we are entering – if not already immersed in – a social landscape in which our identities are not lived but performed, and our existence is not normalised but capitalised upon.

How do we recalibrate so that we may embrace identity without being reduced to it? At the very least it requires an acknowledgement that we are not here to tick boxes with our difference. We tell stories not to meet the arbitrary standards of those who unethically wield identity like a cudgel but because humans always have. Our stories are not only cultural records but also historical ones, telling us where we have been and where we can go.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships