Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 JUN 2022

From The Matrix to Euphoria, writer, philosopher and poet Joseph Earp has profiled some of the greatest philosophers, TV shows, films, music and pop culture moments to date, discussing what they can tell us about ourselves and the world.

Which is why we’re excited to share we’ve recently appointed Joseph as an Ethics Centre Fellow. Currently undertaking his PhD at The University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume, we sat down with Joseph for a brief get-to-know-you chat to discuss ethics, his favourite philosophers, and the role of pop culture in society.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

You learn the language of institutional philosophy by reading it, and – as long as your financial and geographical circumstances allow for it – by studying it in an academic setting. But the central questions that drive philosophical work are innate to almost all people, regardless of academic study.

I am a pragmatist, so I don’t believe that philosophers hold insight that stretches beyond the understanding of those who haven’t studied the discipline. As philosophers, we are merely using a certain vocabulary to ask our questions. I grew to love that vocabulary in my late twenties through university study, under the guidance of my honours and PhD supervisor, Anik Waldow and those academics I studied closely with throughout my undergraduate degree. Most notably, these academics include Caroline West, who I believe to be one of our country’s most unique, inspired, and challenging thinkers – even and especially as I disagree with her – and David Macarthur. My study with these people is what drew me to being a philosopher in the strictest sense. But I think we philosophers are, thankfully, just doing what everyone else is doing.

Do you specialise in any key areas?

Generally, I write about popular culture, emotion, and virtue ethics, but my key area of specialisation is the philosophy of sex. I think that we sadly retain, in many cultures, a suspicion and fear of sex – one that infringes on our ability to self-describe and live our most flourishing lives.

I often think of a story about Pablo Picasso. Towards the end of his life, he was so rich and famous that he could draw any object in the world, whether it be a Ferrari or a mansion, and his drawing would be worth more than the object itself. He could sell a sketch of an object, and use the accrued capital to buy that object – which is a way of saying he could create changes by charting what he felt had already changed. It seems to me that’s the potential, and the potential harm, of philosophical thinking. We construct the world by calling it what we think it is, and for a long time, our views on sexuality have created a world that contains a lot of fear and sexual repression, both internally and externally maintained.

Your honours thesis focuses on emotional contagion. What place does emotion have when it comes to ethics?

Personally, I think it’s emotion all the way down when it comes to ethics, as with most things. David Hume is the philosopher that much of my work has operated in the framework of, and I agree with Hume that when we talk about “rationality” – a word that is sometimes conceived as being opposed to emotion – we are really just talking about a certain kind of emotional work.

What have you been working on this year?

One of the most profound experiences of both my intellectual and personal life has been connecting with a community of thinkers whom I met largely through my university work – all of them world-class philosophers, some of them write for, and work with, the Ethics Centre; and some of them no longer consider themselves strictly philosophers at all. In particular, Georgia Fagan, Danielle Turnbull, Finola Laughren, Eleanor Gordon-Smith, Grace Sharkey, Oscar Sannen, Mitch Flitcroft, Alexi Barnstone, Elle Lewis, Mitchell Stirzaker, Henry Barlow, Zach Wilkinson, Finn Bryson, and Henry Hulme.

All of these people have work that you can, and should, find online through an easy Google search, and work which I believe in every case benefits the world, and drives real change. What else is philosophy for? I am continually astonished by the intellect and bravery of these collaborators and friends. I consider myself useless without them. When I think about the real work that I have done this year, it is not anything I have written, but conversations with these people, and the ways I have learnt from them.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or writer?

Hume is the philosopher whose writing I know best, but I believe the thinker you apply the greatest amount of study to is usually the one who you have the strangest, most frequently frustrated relationship with. So my favourite – as in, the philosopher who serves as the background to almost all of what I think and do, and who I have the most uncomplicated connection to – is the pragmatist Richard Rorty. It’s Rorty who cuts through the chaff by asking, again and again, one of the simplest questions: what is the real-world application of our work? And it’s Rorty who tells us that we should remember we can make ourselves whoever we want to be.

Your writing covers a lot of tv series, films and music. Why is pop culture important?

Again – it’s Rorty. Rorty believed that social change isn’t led by philosophers, particularly those analytic philosophers who consider their work to be sorting through “falsehoods” and “truths”. For Rorty, philosophers inspire prophets and poets, and prophets and poets are the ones who do the work of change. That is, for me, the importance of pop culture. That form of art is guided by philosophical questions, and led by prophets and poets, and represents a way of understanding a culture and a vocabulary. It’s how lives are changed, and possibilities for self-description are opened up

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

The poetry collection The Cipher, by Molly Brodak, a writer who means a great deal to me; the pornographic film Corruption by perennial sadsack and visionary Roger Watkins, which I try to return to every month or so; and the song ‘Lark’ by Angel Olsen, often enough that I should probably take a break.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

We all play the game of ethics, and we all want to play it better, and we’ll never play it well. That, in fact, is the joy – the trying, and the starting again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

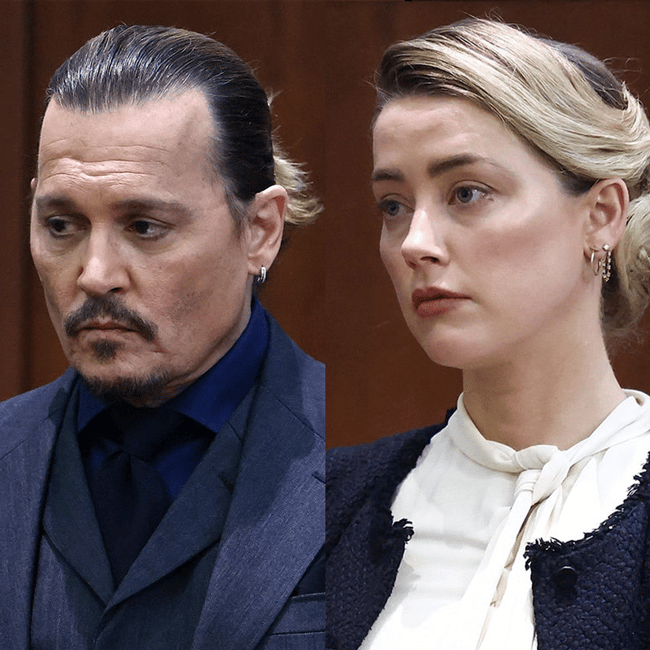

You won't be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 2 JUN 2022

The Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial is now over.

Heard has been found guilty of defaming the actor with an op-ed she wrote – that did not name him explicitly – about being a survivor of domestic violence. Depp’s legal team too has been found guilty of defamation, but the amount that Heard has to now pay Depp is a much higher figure than he has to pay her.

The proceedings are done. But the media reaction to the trial – both from traditional outlets, and the deluge of posts about it crowding every single social platform like ants across an old plate of food – will linger.

This is because, in many circles, the all-too public spectacle has been treated like an unprecedented event. Pored over ad nauseum, it has been subject to endless thinkpieces, YouTube breakdowns, and Twitch streams. Twitter is awash with “fan edits”, compilations of carefully selected moments cut to the jaunty music usually associated with dance trends, or videos of dogs playing with each other in suburban backyards. There’s no use blocking keywords associated with it on social media. Videos still find a way to slip through, because the trial is everywhere.

This isn’t so surprising. The trial is on one level, a glimpse into the personal lives of the usually alien upper class. On another, it is shocking and disturbing enough – whichever side one takes – that it provides the vicious thrills that a culture which has become obsessed with true crime obsessively seeks out. This is all information, content. But how much of it do we need to make an informed decision about the outcome of the trial? And more than that, is this a useful kind of information? Where does it lead us? What does it give us?

The trial is foreign, it’s taboo, it’s ugly, and it’s glossy. What it isn’t, however, is quite as novel as it first seems.

Old Stories; New Faces

Much like the O.J. Simpson trial, or the proceedings against Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton, the Australian woman who claimed a dingo ate her baby, the Depp/Heard case is an example of a media-captivated society channeling abstract arguments through the lens of a high stakes legal proceeding, populated by faces that viewers have already developed complex parasocial relationships with. And, importantly, in each case, there has been an intense public scrutiny on how the figures in these cases should act – a fixation on their body language, their expressions, and the way they sound out words.

During the Simpson trial, the abstract arguments at play concerned race relations. Now, the tensions underlying the Depp/Heard trial are to do with what is sometimes referred to as our “post-metoo world”, a culture that has seen abusers reckoned with, and vast systems of deception that protect those abusers brought to light.

All of these court cases represented, and now represent, an opportunity for the public at large to discuss topics they might not normally have considered polite to bring up at the dinner table, or around the water cooler. “Is O.J. guilty?” was a way of saying, “tell me what you think about race and class in this country.” “Is Amber Heard a liar?” is now a way of saying, “what do you think abuse looks like? And what do we do about it?”

But there is at least one way that the Depp/Heard trial is involved with a trend that is breaking new ground. Unlike the Simpson trial, or the case against Chamberlain-Creighton, most viewers are watching the case through the internet. In turn, that means viewers have a unique ability to craft their own content about the proceedings, filtering key moments pulled from hours of footage through whatever pre-existing narrative they have constructed about the hero and the villain of this painful, and very sad story.

These content creators, who are often cutting together their videos in their spare time for no gain except rallying their audience around them, can watch over the trial’s footage as frequently as they like. They can scrutinize the same few seconds over and over; slow stretches of it down; freeze them in place.

In turn, that has turned a growing number of these amateur video essayists into amateur psychologists. A large subset of Depp/Heard content creators have come to believe that they can work out which of the players are lying by closely watching their expressions, unpacking their body language, and picking over the slightest tic, or absent gaze. For these sleuths, the case’s conclusion is as clear as Heard’s grimace, or the smile unfurling in the corner of Depp’s lips.

The Face Of A Liar

Those who seek to excavate the “truth” hiding beneath the trial by studying the body language and facial expressions of Depp and Heard start from a justifiable philosophical position. It was the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, a famous monist, who believed that every bodily state is underwritten by a mental state. For Spinoza, all things are of the one matter – variously called “nature”, or “God” by his intellectual interpreters. On this view, there is no distinction between any two substances, let alone a distinction between the way we hold ourselves, and what we think. The mind is the body, and the body is the mind.

From this starting point, it makes some sense to believe that the flesh might hold some insight into the secret thoughts and desires of two people who are very famous and very rich – and thus largely inaccessible, because nothing buys privacy like money and influence. Or, if not insight, then evidence gathered as post-hoc justification. Decisions as to guilt change based on a variety of factors – but they’re sometimes made early, and data can be gathered after those decisions have already been made, propping up pre-existing positions.

The mistake, however, is to generalise what these embodied states look like, and thus to generalise the emotional and mental states they are tied to.

There is, quite simply, no one way that all of us look when we lie, or are distressed, or happy. We are distinct in the way that we consider the world around us, and thus distinct in the way that we physically appear when we do.

Many of the “tell-tale signs” that get neurotically returned to, over and over again, on social media – Heard’s tone of voice, Depp’s drawl – could have any number of associated affective states, from anxiety, to pain, to yes, perhaps, the desire to lie. “It can be tough to accurately interpret someone through their body language since someone may feel tense or look uneasy for so many reasons,” said the therapist and author Dr. Jenny Taitz.

If we follow Spinoza, we will believe that our bodies and our thoughts are intertwined – but that’s not the same as saying the former will reveal the latter. These are slabs of affect, expressed both physically and mentally, but they are not as easily comprehensible as that makes them sound.

Indeed, psychological studies have proved for decades that none of us are skilled when it comes to weeding out those spinning “falsehoods”, and those not. A 2004 study of lying found that “agents of the FBI, the CIA and the National Security Agency – as well as judges, local police, federal polygraph operators, psychiatrists and laymen – performed no better at detecting lies than if they had guessed randomly.”

There is, after all, an immense social advantage to picking liars. If we could do it, and do it reliably, then that would be an invaluable skill, one we would expect to spread and be adopted across communities quickly. The fact that there is no dominant method of analysing the way our bodies twist and pose when speaking in itself speaks to the impossibility of using faces to get at what we mean when we talk about “the truth.”

Moreover, even most “body language experts” – an increasingly popular and media-saturated sub-set of pop psychologists, who have almost no science to back up their claims – admit that we need to get a baseline of our subject’s physical reactions before we can even attempt the fraught and mostly doomed work of trying to understand if they’re lying.

Which is to say, we need to at least know what people look like when they’re telling the truth before we can tell if they’re not. And we don’t know Johnny Depp, or Amber Heard, despite the illusion of closeness granted by social media. We don’t have enough data about how they move through the world, or what they look like when they do. How could we possibly guess at the motives and thoughts of utter strangers?

The Actors

Heard’s critics in particular have developed the line that she is a “performer”, going through the mere motions of grief and trauma – and not particularly well. They highlight a moment in which Heard appeared to pause while waiting for a cameraperson to snap a picture of her pained face, and another in which she seemed to flicker, composing herself for her next line as an actress on set would.

Of course, Heard is performing, on some level. But she is not performing in a way different to Depp. Though his defenders do not often note it, he too is signaling to the cameras, and to the jury – his smiles, and asides to his legal team, make that clear.

Nor, even, are these two distinct from the rest of us. We are all performing. We are social creatures, who have the ability to tell when we are being watched by others. Theory of mind, the term used to describe our understanding that other human beings see and think like we do, means that we can throw ourselves into the perspective of our observers. We do this constantly. It is part of what it means to have a body, and to be a person.

As philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre pointed out, we don’t even have to be actively watched to know that we could be watched. We carry with us the sense that we are what Sartre called a “thing in the world” – an entity that, at any time, could be stumbled across, and studied. As a result, we are always aware of ourselves, and how we might appear. Even when we are totally alone, we are never really alone. We are always with others – whether they’re flesh and blood observers, or ones we’ve made up in our head.

Where The Truth Lies

None of this has been an attempt to argue that Depp is telling the truth over Heard, or vice versa. It is not even a question of “truth”, as that word has been contemporaneously used.

The binary between the “real” and the “fake”, aggressively emphasised in media reactions to the trial, is itself overly simplistic, an outdated harbinger dangerously trickled down into the culture by analytic philosophy.

That is not to diminish the hurt, or the trauma, that clearly sits at the centre of the trial. That pain is real. That pain can be understood, but only when we look at the evidence in totality – the actual evidence, not the faces on the stand – and then causally tie it to certain parties.

We should, however, remember there is no objective state of affairs – no perfect place from which, like God, we can dispel the lies and embrace the world as it really is. The judge overseeing the Depp/Heard trial is not neutral. None of us are. At best, in this case as in so many others, we should, like the great pragmatist Richard Rorty, argue for ethnocentric justification for our claims, rather than tying them to a standpoint that sits outside of history, and belief, and bias. In doing so, we can embrace the changeability of our own positions – not on guilt and innocence, exactly, but the societal pressures that are so at play here – and examine them, seeing them as the flexible systems of thought that they are.

Throughout, however, we should remember that whatever we’re looking for when we hope to untangle a messy and painful relationship between two strangers who we will almost certainly never meet, it will not be found in their faces.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 10 MAY 2022

Yellowjackets, with its widely acclaimed first season, has a more disturbing element than its surface of considerable violence and horror.

Sure, the Showtime series, which follows a group of young athletes as they crash-land following a disastrous plane trip in the middle of the wilderness and turn, with visceral, enjoyable brevity, to cannibalism and taboo-shattering behaviour, contains a lot in the way of gore. There are broken limbs; bodies eating up bodies; physically construed nightmares which the protagonists cannot escape.

But underneath that immediate level of violence is a claim, considerably more unsettling than fractured calcium, that our ethical systems are far from stable and robust. We’re not bent towards virtue. We seem to be shaped in the opposite way. Yellowjackets knows that. And more than that, the show loves it.

Corruption Seeps In, Naturally

Yellowjacket’s “heroes” – a word which only means to indicate those characters who are applied with a particular, and frequently intense, narrative scrutiny – are the stereotypes of “ordinary” people. The show, which flips back and forth between the present and the deep, traumatic past, makes a great deal of effort to depict that. There are extended shots of the central characters, moving their way through the world, not even thinking about the trauma they inflicted on others, deep in their pasts.

Indeed, the flashback structure of proceedings, one that allows the central mystery to unfurl slowly – who ate who, following that terrible plane crash? – mines much from the main characters’ attempts to live their lives freely in the aftermath of their great collectively-constructed horror.

In the show’s temporal present, these plane crash survivors are all people who wake up every day, and apply themselves to their jobs, and are loved and love in turn. You’d meet them, and catch their eyes in a shopping centre, and smile, astonishingly oblivious of their histories. It’s only when we get painful stabs of their past, unfolded in flashback, that we come to understand that there is something hiding here; a history streaked by vicious behaviour.

That “something” can’t be pinned down to the specifics of our heroes’ lives, either. We can’t shirk the implication that we’d fail to avoid the same behaviour – it is nothing less than the human capacity for violence. We are all confronted, more frequently than we would like to admit, with the idea that we have a potential for evil.

Remember that time you stood on the train platform, and considered, all of a sudden, pushing a stranger onto the tracks? Not for any reason – just because you could. Because, despite what we hope ethics might teach us, there’s something actively joyful about vicious behaviour.

Yellowjackets doesn’t make anything extraordinary out of its central characters. These are just human beings, ones who happen to have been freed – predictably, almost boringly – from the social code of morality, and plunged into horror. We all could be there. All that Yellowjackets tells us is that, most worrying of all, we would enjoy it.

So Why?

The philosopher David Hume constructed his ethical system out of twin poles: pleasure and pain. Hume believed that we all have a natural repulsion to pain, and an attraction to pleasure. That, for him, was the foundation of all ethical behaviour, the starting point that explains empathy, charity, and goodness.

Yellowjackets tells us that’s not true. The show’s spark of originality is not to prove that we all have a propensity for inflicting suffering. That’s already been explored through multiple works of art – consider, for example, the Netflix smash hit Squid Game, which should be considered the contemporary final word on what happens when you guide desperate people towards viciousness.

No. What makes Yellowjackets special is that its central characters have spent the rest of their lives following the plane crash pursuing the highs of gnawing on another human being. They’re not tortured – they’re hungry.

We Do What We Want – Thank God

If that sounds horrifically bleak, it’s because, despite its considerable vein of humour, Yellowjackets is horrifically bleak. We are inundated with art that aims to provide us with a moral compass, designating bad and good behaviour, and telling us how to navigate both. The thematic work, quite often, in these pieces of popular culture, is to condition us emotionally – to train us to be repulsed by horror, and drawn to goodness.

Yellowjackets does not do this. It makes the horrendous appear attractive: “look at these regular people, who ate one another, and defied the social norm, and found themselves in the process.” And it makes the virtuous seem weak: “look at those fools who let their sense of goodness stop them from doing what they want to do.”

If there’s any hope here, then, it’s our capacity to understand pleasure and pain in a more complicated way than Hume did, and that much contemporary art concerned with morality encourages us to do so. Rather than monoliths of feeling – this is pleasurable, and thus morally good; this is not pleasurable, and thus morally bad – Yellowjackets encourages us to mine the depth of our affect, and see it as being filled with nuance.

As Yellowjackets teaches us, we can’t hope that we will have an intrinsic and affective pull away from vicious behaviour, and a pull towards virtuous behaviour. What we can hope, instead, is that we understand our emotional states of pleasure and pain as containing more complexity than mere repulsion and attraction. We should become the experts in our own emotional states – not merely how they feel, but how they tell us to act.

After all, as plane crash victims who begin gnawing on each other’s bones tell us – not to mention addicts, or those who hurt the people they love – we can sink, pleasurably, into horror, and feel good about things that we don’t like, or no longer want to do.

We will never extinguish the joy of doing something we know we shouldn’t do. That’s the kid peeking at the Christmas presents before he should; of turning to our friend, maimed in a plane crash, and eyeing up their naked leg, considering our teeth in it. But what we can do is explore those feelings, and truly feel their complexity, and understand that no affect leads us more closely to one conclusion than any other. It’s up to us. That’s scary. But it’s also beautiful.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 MAR 2022

Slavoj Žižek (1949-present) is a contemporary leftist intellectual involved in academia as well as popular culture. He is known for his academic publishing in continental philosophy, psychoanalysis, critique of politics and arts, and Marxism.

Žižek is remarkable for combining an esoteric life of abstract academic enjoyment with political activism and engagement with current affairs and culture. His political life goes back to the 1980s when he campaigned for the democratisation of his home country, Slovenia (then part of Yugoslavia), and ran for the Slovenian presidency on the Liberal Democratic Party ticket in 1990. He has since become known as one of the world’s leading communist intellectuals, although he is far from dogmatic. Žižek has aroused controversy with his revisionary takes on Marxism, criticisms of political correctness and strategic support of Donald Trump in 2016.

Žižek is known as a provocateur, trigger-happy with an arsenal of dirty jokes, ethically challenging anecdotes, extreme statements, and stark inversions of glib platitudes. But his ‘intellectualism’ and provocations are neither nihilistic nor unprincipled.

Žižek’s oldest loves are cinema, opera and theory. He is sincerely committed to art and ideas, seeing them as both tools for sharpening up political struggle as well as part of what that struggle is ultimately all about. As he once put it: “we exist so that we can read Hegel.” That is, while philosophy may be useful, it’s also an end in itself, and needs no practical application to justify its existence or enjoyment.

As for his provocations, they are either the expression of a genuine, open-minded inquiry, or an effort to liberate us from the gravitational force of what he calls ‘ideology,’ a central target of his work.

Indeed, the revival of the Marxist notion and critique of ideology is one of Žižek’s most profound contributions to the contemporary conversation in this space and is a key part of his innovative synthesis of Lacanian and Marxist theory.

For Žižek, ideology is not primarily about our conscious political beliefs.

Instead, ideology is something that shapes our everyday behaviour, norms, habits of thought, architecture and art. It can be found everywhere from Starbucks coffee and toilet seat designs to Hollywood cinema. To engage with Žižek on ideology is therefore to engage with all aspects of life – culture, psychology, love, politics.

Inspired by Karl Marx, Žižek sees ideology as part of what supports a given social, economic and political system. It keeps us doing the things that keep the wheels of the system turning, regardless of what we consciously think. Žižek’s role, as he sees it, is to help bring this ideology to our attention so that we may break free of it. This liberation is essential to the ultimate goal for Žižek: replacing the liberal-capitalist order we currently occupy. To do this, Žižek strives to break the spell of ideology through a kind of psychoanalytic shock therapy that cannot be co-opted by ideological discourse.

“For Žižek, jokes are amusing stories that offer a shortcut to philosophical insight.” (Žižek’s Jokes)

When Žižek affirms Stalinism or prescribes gulags, for example, he isn’t being purely ironic nor purely sincere. His intention is instead to evade the clutches of superficial platitudes that narrow our thinking. In doing so, Žižek wants to “rehabilitate notions of discipline, collective order, subordination, sacrifice” – values that are too easily either neutralised by a bland and inoffensive liberalism that preserves the current social order or demonised via the “standard opposition of freedom and totalitarianism.”

Žižek’s analysis of ideology provides us with some of the tools we need to do this sort of ‘shock-therapy’ for ourselves. He explores the ways in which ideology manages to preserve the system we occupy through such mechanisms as cynicism, “inherent transgression” and the rhetoric of neutrality.

That is, cynicism allows us to knowingly act contradictory to our beliefs with little or no mental anguish.

In this way, the problem is not, as Marx put it in Capital: “They do not know it, but they are doing it.” Rather, it is, to use Žižek’s reformulation:

“They know it, but they are doing it anyway.”

Criticism of capitalism, for example, can thus live quite happily and indefinitely within its inner sanctum, as Hollywood films repeatedly demonstrate. (Here Žižek sometimes likes to cite the 2008 animated film Wall-E).

Žižek continues to be an unpredictable and idiosyncratic voice in politics and culture, difficult to place in partisan terms. Armed with the ferocious joy that he takes in theory and inversion – a joy that opposes all that is easy and superficial – he calls upon us to reflect seriously and radically upon ourselves and our society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Life and Debt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 28 FEB 2022

Euphoria has been, for almost two years now, approaching a fever pitch of horror, addiction, heartbreak and self-destruction.

Its assembled cast of characters – most notably Rue (Zendaya), who starts the first season emerging straight out of rehab – sit constantly on the verge of total nervous collapse. They are always one bad party away from cataclysmic suffering, their lives hanging in a painful balance between “just about getting by” and “absolute devastation.”

Indeed, even if its utter melodrama means that Euphoria doesn’t actually reflect how high school is – who could cram in that much explosive melancholy before the lunch bell? – it certainly reflects how high school feels. There are few experiences more tortured and heightened than being a teenager, when your whole skin feels on fire, and possibilities splinter out from in front of your feet at every single moment. There is the sense of the future being unwritten; of your life being terrifyingly in your own hands.

But what does Euphoria’s constant hysteria do to its viewers, particularly its younger ones? If the devastation of adolescence really is that severe, then are artists failing, somehow, if they merely reflect that devastation? Should we ask our art to serve an instructional purpose; to pull us out of the traps we have built for ourselves? Or should art settle into those traps, letting their metal teeth sink into their skin?

Image: Euphoria, HBO

The Long History Of “Evil” Art

The question of the moral responsbility of artists is particularly pertinent in the case of Euphoria because of its emphasis on what have been typically viewed as “illicit” activities, from drug-taking to underage sex. These are – to the great detriment of a truly free society – taboo subjects, deemed inappropriate for discussion in public spaces, and condemned to be whispered, rather than shouted about.

Indeed, there is a long history of conservatives and moral puritans rallying against artworks that they feel ‘glamorize’ or somehow indulge bad and illegal behaviour. Take, for instance, the Satanic Panic that gripped the United Kingdom in the ‘80s. Shortly after the advent of home video, the market became flooded with what were then termed “video nasties”, a wave of cheaply made horror films that actively marketed themselves for their moral repugnance. The point was how many taboos could be broken; into how much blood and muck and horror that filmmakers could sink themselves, like half-formed and discarded babies being thrown to rest in a mud puddle.

This, to many pro-censorship thinkers at the time, was seen as a kind of moral crime – an unspeakable act, with the ability to influence and addle the minds of Britain’s younger generation. The demand from conservatives was that art be a way of modelling good ethical behaviour, and the worry, expressed furiously in the tabloids, was that any other alternative would lead to the breakdown of society itself.

So no, the question as to whether art should be instructional is not new; the fear that it might lead the minds of the younger generation astray far from fresh. Euphoria might seem relentlessly modern, with its lived-in cinematic voice, and its restless politics. But it is part of a tradition of artworks that submerge themselves in darkness and despair; vice and what some, most of them on the right, deem the immoral.

The Unspoken Becomes Spoken

The mistake made, however, by those who imagine such art is failing an explicit moral purpose, a kind of sentimental education, rests on an outdated and functionally useless understanding of morality. These critics imagine that there is just one way to live well. They believe in uncrossable boundaries of taboo and immorality; that there are iron-wrought moral rules, and that any art that breaks those rules will lead to some kind of negative and harmful shifting of what is acceptable amongst the citizens of any democratic society.

But why should we believe that morality is so strict? We would do well to move away from an objective, centralised view of morality, where there exists a list of rules, printed in indelible ink somewhere, that are inflexible and pre-ordained. Societally, as well as personally, change is the only constant. If we abide by a set of constructed ethical principles that do not reflect that change, we will be forever torn between a possible future and a weighty past, bogged down in a system of conduct that no longer represents the complexity of what it means to be human.

If we have any true moral imperative, it is to constantly be in the process of testing and re-shaping our morals. It was John Stuart Mill who developed a similar concept of truth – who believed that we could only remain honest, and democratic, if we were forever challenging that which we had taken for granted. Art is a process of this moral re-shaping. Great art need not shy away from that which we hold to be “good” or “right”, or, on the flipside, “harmful” and “taboo.”

It is not that art need to be amoral, free from ethical concerns, with artists resisting any urge to provide some form of moral instruction – it is that we need to let go of the idea that this moral instruction can only take the form of propping up old and unchanging notions of goodness. The immoral and the moral are only useful concepts if they teach us something about how to live, and they will only teach us something about how to live if we make sure they are forever being tested and examined.

Finding Yourself

Image: Euphoria, HBO

This is what Euphoria does. By basking in that which has been taken as illicit – in particular, the sex and chemical lives of America’s teenagers – the show makes the unspoken spoken. It draws into focus an outdated and ancient view of the good life, and challenges us to stare our conceptions of self-perpetuation and self-destruction in the face.

Rue, forever in the process of re-shaping herself in the shadow of her great addiction, makes mistakes. Cassie (Sydney Sweeney), Euphoria’s shaking, panic-addled heart, makes even more. Both of them stray from pre-written social conceptions of the “good girl”, dissolving an ancient and harmful angel/whore dichotomy, and proving that there are no static boundaries between what is admirable and what is abhorrent.

Just as the show itself skirts back and forth across the line between our notions of the ethical and the immoral, so too do these characters forever find themselves testing the limits of what is good for them, and those around them. They are flawed, vulnerable people. But in these flaws – in this very notion of trembling possibility, the rules of good conduct forever being written in sand – they do provide us with a moral education. Not one that rests on simplistic notions of what we should do, and when. But one that proves that as both a society, and as individuals in that society, we should always be taking that which has been shrouded in darkness and throw it – sometimes painfully – into the light.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 FEB 2022

Ethics is about engaging in conversations to understand different perspectives and ways in which we can approach the world.

Which means we need a range of people participating in the conversation.

That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Dr Tim Dean as our Senior Philosopher. An award-winning philosopher, writer, speaker and honorary associate with the University of Sydney, Tim has developed and delivered philosophy and emotional intelligence workshops for schools and businesses across Australia and the Asia Pacific, including Meriden and St Mark’s high schools, The School of Life, Small Giants and businesses including Facebook, Commonwealth Bank, Aesop, Merivale and Clayton Utz.

We sat down with Tim to discuss his views on morality, social media, cancel culture and what ethics means to him.

What drew you to the study of philosophy?

Children are natural philosophers, constantly asking “why?” about everything around them. I just never grew out of that tendency, much to the chagrin of my parents and friends. So when I arrived at university, I discovered that philosophy was my natural habitat, furnishing me with tools to ask “why?” better, and revealing the staggering array of answers that other thinkers have offered throughout the ages. It has also helped me to identify a sense of meaning and purpose that drives my work.

What made you pursue the intersection of science and philosophy?

I see science and philosophy as continuous. They are both toolkits for understanding the world around us. In fact, technically, science is a sub-branch of philosophy (even if many scientists might bristle at that idea) that specialises in questions that are able to be investigated using empirical tools, hence its original name of “natural philosophy”. I have been drawn to science as much as philosophy throughout my life, and ended up working as a science writer and editor for over 10 years. And my study of biology and evolution transformed my understanding of morality, which was the subject of my PhD thesis.

How does social media skew our perception of morals?

If you wanted to create a technology that gave a distorted perception of the world, that encouraged bad faith discourse and that promoted friction rather than understanding, you’d be hard pressed to do better than inventing social media. Social media taps into our natural tendencies to create and defend our social identity, it triggers our natural outrage response by feeding us an endless stream of horrific events, it rewards us with greater engagement when we go on the offensive while preventing us from engaging with others in a nuanced way. In short, it pushes our moral buttons, but not in a constructive way. So even though social media can do good, such as by raising awareness of previously marginalised voices and issues, overall I’d call it a net negative for humanity’s moral development.

How do you think the pandemic has changed the way we think about ethics?

The COVID-19 pandemic has both expanded and shrunk our world. On the one hand, lockdowns and border closures have grounded us in our homes and our local communities, which in many cases has been a positive thing, as people get to know their neighbours and look out for each other. But it has also expanded our world as we’ve been stuck behind screens watching a global tragedy unfold, often without any real power to fix it. But it has also made us more sensitive to how our individual actions affect our entire community, and has caused us to think about our obligations to others. In that sense, it has brought ethics to the fore.

Tell us a little about your latest book ‘How We Became Human, And Why We Need to Change’?

I’ve long been fascinated by the story of how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today. Morality has played a key part in that story, helping us to have empathy for others, motivating us to punish wrongdoing and giving us a toolkit of moral norms that can guide our community’s behaviour. But in studying this story of moral evolution, I came to realise that many of the moral tendencies we have and many of the moral rules we’ve inherited were designed in a different time, and they often cause more harm than good in today’s world. My book explores several modern problems, like racism, sexism, religious intolerance and political tribalism, and shows how they are all, in part, products of our evolved nature. I also argue that we need to update our moral toolkit if we want to live and thrive in a modern, globalised and diverse world, and that means letting go of past solutions and inventing new ones.

How do you think the concepts of right and wrong will change in the coming years?

The world is changing faster than ever before. It’s also more diverse and fragmented than ever before. This means that the moral rules that we live by and the values that drive us are also changing faster than ever before – often faster than many people can keep up. Moral change will only continue, especially as new generations challenge the assumptions and discard the moral baggage of past generations. We should expect that many things we took for granted will be challenged in the coming decades. I foresee a huge challenge in bringing people along with moral change rather than leaving them behind.

What are your thoughts on the notion of ‘cancel culture’?

There are no easy answers when it comes to the limits of free speech. We value free speech to the degree that it allows us to engage with new ideas, seek the truth and to be able to express ourselves and hear from others. But that speech comes at a cost, particularly when it allows bad faith speech to spread misinformation, to muddy the truth, or dehumanise others. There are some types of speech that ought to be shut down, but we must be careful how the power to shut down speech is used. In the same way that some speech can be in bad faith, so too can be efforts to shut it down. Some instances of “cancelling” might be warranted, but many are a symptom of mob culture that seeks to silence views the mob opposes rather than prevent bad kinds of speech. Sometimes it’s motivated by a sense that a speaker is not just mistaken but morally corrupt, which prevents people from engaging with them and attempting to change their views. This is why one thing I advocate strongly for is rebuilding social capital, or the trust and respect that enables good faith discourse to occur at all. It’s only when we have that trust and respect that we will be able to engage in good faith rather than feel like we need to resort to cancelling or silencing people.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Ethics is what makes our species unique. No other creature can live alongside and cooperate with other individuals on the scale that we do. This is all made possible by ethics, which is our ability to consider how we ought to behave towards others and what rules we should live by. It’s our superpower, it’s what has enabled our species to spread across the globe. But understanding and engaging with ethics, figuring out our obligations to others, and adapting our sense of right and wrong to a changing world, is our greatest and most enduring challenge as a species.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

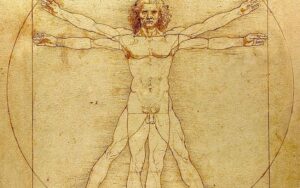

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Research shows that physical appearance can affect everything from the grades of students to the sentencing of convicted criminals – are looks and morality somehow related?

Ancient philosophers spoke of beauty as a supreme value, akin to goodness and truth. The word itself alluded to far more than aesthetic appeal, implying nobility and honour – it’s counterpart, ugliness, made all the more shameful in comparison.

From the writings of Plato to Heraclitus, beautiful things were argued to be vital links between finite humans and the infinite divine. Indeed, across various cultures and epochs, beauty was praised as a virtue in and of itself; to be beautiful was to be good and to be good was to be beautiful.

When people first began to ask, ‘what makes something (or someone) beautiful?’, they came up with some weird ideas – think Pythagorean triangles and golden ratios as opposed to pretty colours and chiselled abs. Such aesthetic ideals of order and harmony contrasted with the chaos of the time and are present throughout art history.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c.1490

These days, a more artificial understanding of beauty as a mere observable quality shared by supermodels and idyllic sunsets reigns supreme.

This is because the rise of modern science necessitated a reappraisal of many important philosophical concepts. Beauty lost relevance as a supreme value of moral significance in a time when empirical knowledge and reason triumphed over religion and emotion.

Yet, as the emergence of a unique branch of philosophy, aesthetics, revealed, many still wondered what made something beautiful to look at – even if, in the modern sense, beauty is only skin deep.

Beauty: in the eye of the beholder?

In the ancient and medieval era, it was widely understood that certain things were beautiful not because of how they were perceived, but rather because of an independent quality that appealed universally and was unequivocally good. According to thinkers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, this was determined by forces beyond human control and understanding.

Over time, this idea of beauty as entirely objective became demonstrably flawed. After all, if this truly were the case, then controversy wouldn’t exist over whether things are beautiful or not. For instance, to some, the Mona Lisa is a truly wonderful piece of art – to others, evidence that Da Vinci urgently needed an eye check.

Consequently, definitions of beauty that accounted for these differences in opinion began to gain credence. David Hume famously quipped that beauty “exists merely in the mind which contemplates”. To him and many others, the enjoyable experience associated with the consumption of beautiful things was derived from personal taste, making the concept inherently subjective.

This idea of beauty as a fundamentally pleasurable emotional response is perhaps the closest thing we have to a consensus among philosophers with otherwise divergent understandings of the concept.

Returning to the debate at hand: if beauty is not at least somewhat universal, then why do hundreds and thousands of people every year visit art galleries and cosmetic surgeons in pursuit of it? How can advertising companies sell us products on the premise that they will make us more beautiful if everyone has a different idea of what that looks like? Neither subjectivist nor objectivist accounts of the concept seem to adequately explain reality.

According to philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Francis Hutcheson, the answer must lie somewhere in the middle. Essentially, they argue that a mind that can distance itself from its own individual beliefs can also recognize if something is beautiful in a general, objective sense. Hume suggests that this seemingly universal standard of beauty arises when the tastes of multiple, credible experts align. And yet, whether or not this so-called beautiful thing evokes feelings of pleasure is ultimately contingent upon the subjective interpretation of the viewer themselves.

Looking good vs being good

If this seemingly endless debate has only reinforced your belief that beauty is a trivial concern, then you are not alone! During modernity and postmodernity, philosophers largely abandoned the concept in pursuit of more pressing matters – read: nuclear bombs and existential dread. Artists also expressed their disdain for beauty, perceived as a largely inaccessible relic of tired ways of thinking, through an expression of the anti-aesthetic.

Nevertheless, we should not dismiss the important role beauty plays in our day-to-day life. Whilst its association with morality has long been out of vogue among philosophers, this is not true of broader society. Psychological studies continually observe a ‘halo effect’ around beautiful people and things that see us interpret them in a more favourable light, leading them to be paid higher wages and receive better loans than their less attractive peers.

Social media makes it easy to feel that we are not good enough, particularly when it comes to looks. Perhaps uncoincidentally, we are, on average, increasing our relative spending on cosmetics, clothing, and other beauty-related goods and services.

Turning to philosophy may help us avoid getting caught in a hamster wheel of constant comparison. From a classical perspective, the best way to achieve beauty is to be a good person. Or maybe you side with the subjectivists, who tell us that being beautiful is meaningless anyway. Irrespective, beauty is complicated, ever-important, and wonderful – so long as we do not let it unfairly cloud our judgements.

Step through the mirror and examine what makes someone (or something) beautiful and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for the Ethics of Beauty on Thur 29 Feb 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Free speech has failed us

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 26 DEC 2021

It is one of the most iconic scenes in modern cinema, Neo (Keanu Reeves) sits before the sage-like Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) in a room slathered with shadows, and is offered a choice.

Warning: this article contains spoilers for The Matrix Resurrections

Either he can take the blue pill, and continue his life of drudgery – a digital front, as it turns out, to stop human beings from realising they are nothing but batteries to power a race of vicious machines – or take the red pill, and awaken from what has only been a dream.

The image of this fateful choice has been co-opted by conspiracy theorists, endlessly picked over by film scholars, and referenced in a thousand parodies. But perhaps the most interesting critique of the scene comes from Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek. Why, Zizek asks, is there this binary between the imagined or “fake” life, and the real one? What is the distinction between fantasy and reality; how can one state ever exist without the other? There is no clean separation between the lives we live in our heads, and the so-called external world, no line that we can draw between the artificial and the authentic.

Maybe Lana Wachowski, the director of the newest iteration in the franchise, The Matrix: Resurrections, heard Zizek’s words. Early on in the film, Resurrections re-stages a version of Neo’s fateful choice from the first instalment. But this time the falseness of the choice has been revealed: he is offered only the red pill. The binary between fake and real has been destroyed. Whatever path he takes – whether he comes frightfully into consciousness in his vat of goo, his body tended to by the tendrils of machine, or continues to pad through a life of capitalist turmoil – he is only ever in his own head.

The Cage of Our Own Heads

Solipsism, the belief that only the mind exists – and not any old mind, your mind – has its roots in Cartesian skepticism. It was René Descartes who found himself plagued by a nagging worry: what if everything that he could see, smell, and hear was merely the conjurings of a demon, tricking him into sensations that he could not prove are real? Or, in the language of the Matrix: what if our entire world is a construct, as cage-like and bleak as the containers that cattle are exported to the abattoir in?

Descartes, doubting the existence of reality itself, came to believe that there were only two things one could be sure of. The first, as he famously pronounced, is the existence of at least one mind: “I think therefore I am.” After all, if there wasn’t a mind to wonder about the nature of reality, then there wouldn’t be any wondering about the nature of reality. The other, less frequently discussed foundation of truth that Descartes believed in was the existence of God: if at least one mind exists, then God must have created it, Descartes thought.

Resurrections accepts only the first premise. There is no hope that God might exist out there, in the ether, an entity to pin some sense of certainty upon.

It is a film about being entirely trapped in a subjective experience that you cannot fully verify; held captive in the shaky cage of your own mind.

When we meet Neo, he is seeing a therapist, in recovery from a suicide attempt. The source of his suffering? That he is plagued constantly by memories that don’t seem to belong to him; that he is filled, always, with a nostalgia for a past he is not sure he has even lived; that he is concerned the fictional stories that he tells as a game designer might in fact as authentic as the desk he sits at, the boss that he serves. Or vice versa: perhaps the desk, the boss, are the entities to be trusted, and the sprawling lines of code that make up the video game are just a joyful illusion.

Neo has no way of verifying the reality of any of these thoughts. They are all just mental constructs, representations that are slowly fed to him for reasons that he cannot fathom, each carried with the same epistemic force. Desperate, he tries to use his therapist, played by Neil Patrick Harris, as his watermark; in what might be fits of paranoid delusion, he calls the man, raggedly trying to work out if he is losing his mind, hoping to dredge apart dreams and the complex mental representation we call “life”.

But as Resurrections later reveals, the therapist is the least trustworthy source that Neo could have turned to. The therapist is not just part of a fantasy that might be a reality, and vice versa: he is its very creator. And his whims, when they are explained at all, are vague and confusing. He is no adjudicator of what is fictive and what is corporeal. He is just one more layer of fantasy-as-reality, and reality-as-fantasy, a mess of whims, and desires, and dreams that exists in two states at once.

Loneliness and Hope

This is, on some level, a comment on our essential loneliness. We might feel as though we are surrounded by people, that there are lives being lived alongside ours. But, Resurrections says, we have no way of understanding the minds of our friends, families, and strangers – they are mysteries to us. Neo’s journey in Resurrections is one of finding a community, the rag-tag group of machines and humans that are hoping for a better world. And yet this community acts in ways he cannot predict; that surprise him. And more than that, he has no way of knowing if they are even real – throughout, he constantly questions whether he has actually awoken, or if he is merely living in complex whorls of fantasy.

But there is hope here too. Resurrections is, amongst other things, a paean to the power of storytelling. Those characters who attempt to dismiss our ability to spin fictions – chiefly the therapist, and the capitalistic Agent Smith, who wants to turn narratives into more products to be sold – are the film’s villains. Its heroes are those who fully embrace the power of the stories that we spin for ourselves, whether they be video games or complex narratives about our own pasts. After all, though it might be bleak to imagine that the external world is always filtered through a shaky subjective experience, that means that our fantasies are as powerful – as life-altering – as anything “real.” The world is forever what we make it.

The Power of Fear and Desire

If we are in total charge of our own destinies, able to spin ourselves into whichever corners that we choose, then what motivates us? After all, if everything is able to be re-written, then what reason do we have for doing any one thing over another?

Total freedom comes with a price, after all; there is a kind of terrible laziness that can descend upon us when we know that we can do whatever we want, a kind of malaise of submission, where, instead of rewriting the world, we sit back, and let it unfurl however it wants.

It is this state that Neo’s fellow video game designers have fallen into, a kind of overwhelming boredom that narrows their scope of possibilities and makes them one more cog in a machine that is completely out of their own control.

But Resurrections has a rebuttal to this laziness. In a key moment in the film, Neo’s therapist explains that the world he has created – the world of the Matrix – is driven, quite simply, by two states. The first is fear; the fear that we will lose what we have, whether that be our minds, in the case of Neo, or our freedoms, in the case of his fellow guerillas. And the second is desire; the world-making force that drives us to move fast, to want more, to continually strive for a different kind of world.

There is a bleak reading to this thesis statement, one that aligns with the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza. Spinoza believed that we are at our least free when motivated by causes outside of control; when our own striving for perfection, what he called our conatus, becomes putrefied and affected by those around us. After all, if we are petrified by fear, and if our hope for a different world is contingent upon the behaviour of others, then we will perpetually be buffeted around by fictions, by memories, by states that are causally connected to forces outside our control. We will be, simply put, trapped, stuck in the ugly cycles of code that Neo spends the first 20 minutes of Resurrections designing.

But there is still, even here, hope. After all, that fear need not be necessary painful; that desire need not be necessarily linked to unstable foundations. If we combine the notion that we are only within our own minds, that our fantasies have as much explanatory power as our “realities”, and this cycle of fear and desire, we can begin to understand how we might rewrite everything. We can make of fear and desire as we wish; we can alter and shape the people who we love, and we dream of.

That is the message encoded in the final shot of the film. Neo and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) have given up on the search of epistemic foundations. They do not kill the therapist who has kept them in the bondage of The Matrix. Instead, they thank him. After all, through his work, they have discovered the great power of re-description, the freedom that comes when we stop our search for truth, whatever that nebulous concept might mean, and strive forever for new ways of understanding ourselves. And then, arm in arm, they take off, flying through a world that is theirs to make of.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 20 DEC 2021

There is a singular thrill that comes from watching very bad people do very bad things.

The anti-hero has been a staple of modern television and cinema for decades, made popular by Tony Soprano splashing about in a swimming pool with a brace of ducks, taking some much needed “me time” after overseeing a truly astonishing number of murders.

This kind of art might have some therapeutic aspects – it teaches us how not to be, so we might learn how to be – but that’s not its purpose. Its purpose is entertainment, the sick, giddy feeling that comes over us when we watch people throw off the entirely artificial rules of morality, and behave however they want.

Moreover, this kind of art is a way of teaching us the manners by which our moral outlooks are shaped by repetition: habit and practice. When we see someone like Soprano do the same evil things, over and over again, we learn about the compounding nature of vice, the way that one bad action spawns a myriad of others.

No show exemplifies that thrill better than Succession. Its characters are vicious, and in both meanings of the term: each week, they tear each other apart, sacrificing even familial bonds for the sake of victories that almost immediately sour in their mouths. They live in a world that is constantly in the process of ratifying, and, briefly, rewarding them; they are shaped by their wealth, and by the uneasy collective they form with each other, in which power is everything and weakness is to be avoided at all costs.

But this gaggle of do-badders are not alike in their foibles. Each principal member of the cast displays a different vice, and has a different way of working towards the same unpleasant ends. Here is a kind of “pick your horror” list of the show’s central players, outlining each of their worst qualities. Which deviant are you?

Logan Roy: The Happy Capitalist

As Peter Singer noted, capitalism thrives on individuation; the idea that we are made up of communities of one, and that it is always better to sacrifice the well-being of others in order to get ahead. And how better to sum up that belief that you should, at all times, consider yourself the number one priority than the behaviour of Logan Roy? Logan has no loyalty – he will hurt whoever he needs to hurt. He is one of the few purely, uncomplicatedly immoral characters of the show, being openly unremorseful. He is, as Aristotle would put it, in total vicious alignment – he feels no urge to do the right thing, and his behaviours line up perfectly with his moral universe, of which he is the centre.

Kendall Roy: The Coward

Speaking of alignment, the character in Succession whose behaviours are most out-of-sync with their desires is Kendall Roy. Unlike Logan, he is not without remorse. Time and time again, he repents – one of the most affecting moments of the recent season was the man on his hands and knees, saying, in a voice of exhaustion, that he has tried. He suffers from a tension that we all feel, one between moral behaviour and immoral behaviour. He wants to be courageous – that is how he sees himself. But his base level desires, many of which he hasn’t even analysed within himself, are in constant conflict with the globalised outlook he has on his moral character. There is a gulf between how he considers himself in the abstract, and how he actually acts, moment by moment.

The problem, in essence, is that Kendall moves too fast. His decisions come too quick, and they are guided by his misplaced desires to appease his father and to feed into the pre-existing drama of the family. Iris Murdoch once wrote that we should train ourselves to live a moral life, habituating good action so we can unthinkingly help others when the time comes. When the time comes for Kendall, as it does with insistent regularity, he unthinkingly makes the wrong choice, sacrificing his own systems of values to appease a man who considers him less than dirt. That’s cowardice in its purest form.

Roman Roy: The Casually Cruel

When we think of evil, we tend to imagine oversized portraits of crooked megalomaniacs, stealing candy from babies and kicking the backsides of puppies. But as philosopher Hannah Arendt tells us, evil need not be enacted by larger-than-life villains. Indeed, Arendt believed that vicious behaviour can be performed in a myriad of tiny ways by the most unassuming of individuals. That is Roman Roy to a tee.

Through the series, Roman appears to be nothing more than a happy-go-lucky hedonist, a man filled to the brim with pleasures, who enjoys the finer things in life. But that happiness also extends to the vicious behaviour of himself and of others. He loves suffering and rejoices in the chaos of his family life. His horrors are pulled off with a smiling face, as though they are nothing but briefly disarming attractions, as inconsequential as a county fair.

Shiv Roy: The Manipulator

It was Immanuel Kant who once wrote that we should always treat those around us as ends in themselves, never as means. Kant thought it one of the great immoralities capable of being enacted by human beings for us to see those around us tools, whose internal lives we need never to consider. After all, for Kant, human beings are the creators of value – there is no goodness intrinsic in the world, and it exists only in the eye of the beholder. Try telling that to Shiv Roy. Shiv sees those around her as mere means of getting what she wants, to be used and discarded on a whim – even her husband is one more bridge to be shockingly burnt after she has crossed it.

Not that Shiv is without redemption. Kant also believed that there is always good will: an iron-wrought and rational understanding of the correct thing to do in any moral situation. His was a virtue ethics founded on principles, and Shiv does, despite herself, have those. Take, for instance, her complicated introduction to the world of politics in season three. She is offered what Peter Singer would call the ultimate choice – the option of winning the race against her siblings for her father’s affections, if she endorses a particularly slimy Republican candidate for President. There are, to our surprise – and maybe even to hers – lines that Shiv will not cross. Turns out even the most manipulative of us can find there are things that we simply will not do.

Cousin Greg: The False Innocent

Innocence can have an intrinsic value: it can be good for itself, in itself. But Cousin Greg, Succession’s scheming dope, uses his innocence instrumentally. He presents himself as being the dumbest person in the room, forever in the process of duping others with his blandness. But there is nothing innocent to the way he acts.

His is a vice that comes from its very duplicitousness – he presents himself one way, as though he never quite understands the situation, and then acts very differently in another. It’s proof, if any more was needed, that virtues can be a disguise that we can drape ourselves in the illusion of good behaviour, for nothing but our own benefit.

Tom Wambsgans: The Sycophant

Loyalty is a morally neutral character trait. It can be virtuous, as when we are loyal to our friends, and it can be vicious, as when we unbendingly act in accordance with an evil benefactor. Tom Wambsgans started Succession as one more foot soldier, a buffoon kicked around by forces much greater than him: no wonder he found a twisted kind of kinship with Cousin Greg, another duplicitous fool. But his loyalty to Logan – his unwavering belief that the sole purpose of his life was to be in the good books of the elder Roy – eventually transformed him into something much more nefarious.

Tom is unwavering in his belief system, utterly obsessed with power, and firmly of the opinion, contra to the writings of Michel Foucault, that it only moves in one direction. Tom wants total power, and he wants it totally. He does not consider, as Foucault did, that the person over whom we hold power also holds power over us. If all of history is a boot stomping on a human face, then that’s Logan’s spit-shined boot, and Tom’s smugly smiling face.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 10 DEC 2021

This week, a group of more than a dozen Rohingya refugees launched a civil suit against Facebook, alleging that the social media giant was responsible for spreading hate speech.

The victims of an ongoing military crackdown in Myanmar, the refugees claimed not merely that Facebook allowed users to express their anti-Rohingya views, but that Facebook radicalised users – that, in essence, the platform changed beliefs, rather than merely providing a conduit to express them.

The suit is, in many ways, the first of a kind. It targets the manner in which systems – whether they be social media giants, video streaming sites like YouTube, or the myriad of bureaucracies that we all engage with in one way or another almost every day – warp and change beliefs.

But what if the suit underestimates the power of these systems? What if it’s not merely that social and financial enterprises alter beliefs, but that these enterprises have belief sets entirely of their own? More and more, as capitalism continues to ratify itself, we are finding ourselves swept up in communities that operate on the basis of desires that are distinct from the views of any one member of those communities. We are all part of a great, groaning machinery – and it doesn’t want what we want.

Pawns in a Game

There is a key sequence in David Simon’s critically adored television series The Wire that sums up this perspective perfectly. In it, three young men, all of them members of a rickety enterprise of crime, find themselves playing chess. The least experienced man does not understand the game – how, he wants to know, does he get to become the king? He doesn’t, the most experienced man explains. Everyone is who they are.

Still, the younger man wants to know, what about the pawns? Surely when they reach the other side of the board, and get swapped out for queens, they have made it – they have beat the system. No, the experienced man explains. “The pawns get capped quick,” he says, simply.

There is a deep, sad irony to the scene: the three men are all pawns. They have no way of beating the system. They will not even live to become queens. When one of them dies a few episodes later, shot to death by his friend, there is a grim finality to the murder. He did, as expected, get capped quick.

This is the focus of The Wire – the observation that members of any community are expendable when weighed against the desires of that community. The game of chess is bigger than any of the pawns could imagine, a system with its own rules that they are merely contingent parts of. And so it goes with the business of crime.