Big Thinker: Henry Thoreau

A tax evader, rebel philosopher and the grandfather of environmentalism, Henry Thoreau (1817—1862) practiced a back-to-nature experience of the natural world while opposing authority.

Though enjoying no great acclaim in his lifetime, today the name Henry David Thoreau resonates across philosophy, literature, political history, natural history and environmental science. His spirit of non-conformity, his rugged individualism and his ‘essentialist’ approach to living, have seen him mythologised as an American hero – and an ancestor of various ‘return to nature’ movements, too.

The son of a pencil maker, Thoreau was born in 1817 in Massachusetts, US. He demonstrated free minded dissent for institutions early in life. While at Harvard, he allegedly refused to pay for his diploma certificate. In his subsequent role as teacher, he rejected a recommendation for corporal punishment – by thrashing a random group of students to make a point, then resigning. Later, he would refuse to pay six years’ taxes. He saw it as surrendering his money to fund slavery and the government’s war in Mexico, both of which he vigorously opposed. For this, he was thrown in jail.

Civil Disobedience

Thoreau’s spirit of resistance coalesced in the libertarian manifesto Civil Disobedience. Unjust governments have no right bending citizens to their arbitrary laws and corrupt systems, he argued in the book. A free, enlightened state was only possible once that state “recognised the individual as a higher and independent power”, and enabled them to be “men first, and subject after”.

Rather than meekly obey, Thoreau said he was obliged “to do at any time what I think right” – even if that meant breaking the law. This idea of self-governance by individual conscience would later inspire Gandhi, Martin Luther King and others who took a principled stance against unjust rule.

It has also been widely critiqued. Violent and bigoted acts can, after all, easily be committed under the banner of self-righteousness. And what if two people divided on a matter by ideology or faith can’t settle their differences?

Lines in Civil Disobedience like, “That government is best which governs not at all” also make some question whether Thoreau’s libertarian politics tended towards anarchism.

Simple living, transcendentalism and the Walden experiment

A fellow resident of his home town, Ralph Waldo Emerson was a pivotal influence on Thoreau. He introduced Thoreau to transcendentalism – a movement which reacted against religious and intellectual trends, and enjoined each individual to forge their own “original relation to the universe”. Thoreau became a key figure in the movement. For him, solitude, simplicity, awareness and harmonious engagement with the wild were concrete ways to forge this relation. His philosophy as well as his science, insisted upon embodied understanding, rather than just a contemplative or discursive one.

In a forest cabin lent to him by Emerson, Thoreau conducted an experiment in simple living which would last two years and two months. His methods and reflections during this time became the classic work Walden – named after a pond which abutted the property. In it, with poetic eloquence, didacticism and free wheeling style, he lays out his view of a resigned, frivolous and wretched humanity, and how one is to instead rise above and “live deliberately”.

To achieve an existence which is pure and meaningful, Thoreau argued a life must be cultivated free from illusion and excess. He practiced a style of subsistence living through radical self-denial. Only essential needs were identified and met. A plausible misanthrope, he forswore conversation, sensuality, coffee, meat and alcohol, advising just one meal a day. To relinquish to the slightest temptation was to open the gates to moral disrepair. He even eschewed a doormat, “preferring to wipe my feet on the sod before my door.”

According to the American author John Updike, “Waldenhas become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible”.

Kathryn Schulz reads Thoreau’s hermitage as rather a renunciation of responsibility, and categorises it as “original cabin porn”.

“Being forever on the alert”

Shorn of distractions, purged of indulgences, Thoreau believed a greater awareness of the universe can bloom. But more vital to his philosophy was an “ethics of perception” – requiring rigorous attentiveness to the outside world as it was uniquely registered on the senses. This could be observing a sunset’s reflection on glass, or the miniaturised battle of ants. Through this expanded and intensified focus, man was empowered to elevate his life, in “infinite expectation of the dawn”.

A surveyor by trade, Thoreau said we must consciously endeavour to practice “the discipline of looking […] at what is to be seen”.He was suspicious of orthodox forms of knowledge and believed the “essential facts of life” come to us through “the perpetual instilling and drenching of the reality that surrounds us”. Truth, then, was deeply individualised communion between self and world, and the product of intuition and revelation, rather than logic or reason.

Natural as intrinsically valuable

Thoreau’s ideas around nature’s intrinsic value have had significant bearing on modern conservationism. The sublime beauty and order that could be perceived in natural phenomena were not, he thought, qualities projected onto it by humans. They were immanent. What’s more, “Whatever we have perceived to be in the slightest degree beautiful is of infinitely more value to us than what we have only as yet discovered to be useful and to serve our purpose”.

In other words, nature cannot be commodified. Priceless, it must be viewed on its own terms, rather than as a resource to serve human agendas and needs. His view was diametrically opposed to the anthropocentricism that characterised the industrial revolution’s frenzied assault upon lands and oceans, which would culminate in the raft of ecological crises facing us today.

Thoreau also drew attention to the hidden benefits and invisible services of plant and animal species. In one example, he considered the squirrel. To the average American, they were a pest. But if we recognised squirrels in a broader ecosystem context, we could honour them as “planters of forests”, noble little workers whose free labour humans couldn’t do without.

Thoreau recognised, too, that our ignorance of these hidden benefits makes us careless. Trampling over nature’s bounty, upending its fragile balance, we are liable to do untold damage – for which we may ourselves pay a dear cost. In this sense, he was prescient.

“I should be glad if all the meadows on the earth were left in a wild state,” he wrote, “if that were the consequence of men’s beginning to redeem themselves.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 4 DEC 2018

Turning a perceived disability into a new way of solving problems, Temple Grandin (1947—present) has revolutionised the meat-processing industry and changed the way the world views autism.

Temple Grandin is an autism advocate and animal scientist who works to improve animal treatment in the livestock industry. Grandin has also changed public perceptions of autism, helping educators to maximise the strengths of those with autism, rather than focusing only on deficiencies.

An animal lover and meat eater, Grandin has used her autistic trait of “thinking in pictures” to design livestock facilities and educate meat produces on how to minimise animal suffering. As a result, she says there’s been ‘light years of improvement’ in an industry where half of all cattle in the United States are handled in facilities she designed.

This isn’t enough for some animal rights activists though, who accuse her of trying to soften the image of a ‘violent’ sector.

Thinking like a cow

Temple Grandin did not talk until she was three and a half years old. She struggled to communicate throughout her childhood, and other students bullied her at school.But there was one high school teacher, Mr Carlock, who saw something special in her. He mentored the troubled girl and encouraged her to study science.

Shocked by the cruelty she saw in abattoirs, Grandin combined her love for science and animals by fixating on designs to improve animal welfare in these facilities. Grandin knew she learned better by visualising, rather than reading and hearing long strings of words. In this respect, her thinking pattern was similar to animals, who don’t ‘speak’ a language.

She observed cattle in slaughterhouses, seeing how they responded to fear, senses, smells and visual memories. When cows can see they’re about to be killed, they panic, fall and injure themselves. To combat this, Grandin invented the curved loading chutes, which block their vision of what’s ahead, keeping them calm.

This not only improves animal welfare, it saves producers the cost of cattle death, injury and bruising – which also reduces the quality of meat. Grandin has spent her career designing livestock facilities to improve the way animals are treated.

In 1997, she worked with McDonalds after activists exposed animal torture on their production plants. She helped the fast food chain clean up cruel practices and restore its public image.

In 2010, Time Magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world for her work in animal welfare.

We need autistic minds

Grandin has also changed public perceptions of autism, a condition relatively unknown when she grew up. She argues people on the autism spectrum – who tend to struggle with verbal communication but think in pictures – can provide more insight in certain fields than those who think in a more conventional mathematical way.

“Visual thinking is an asset for an equipment designer. I am able to ‘see’ how all parts of a project will fit together and see potential problems.”

Grandin encourages teachers to develop the strengths of autistic children, and has devised clever ways to combat perceived flaws.Like many on the spectrum, she is oversensitive to touch. “I always hated to be hugged”, she says.

So at age 18, she built a ‘squeeze machine’ – two hinged wooden boards lined with foam rubber, which allows users to control the amount and duration of pressure applied. Therapy programs across the United States continue to utilise squeeze machines, with research showing they help relieve stress in users.

Hero or villain?

While considered a hero in the autism community, Grandin’s work divides animal welfare activists. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the world’s largest animal rights group, appreciate and publish her work. Others, like biologist Marc Bekoff, hold that no animal in captivity can enjoy a pleasant life. Bekoff would rather see Grandin encourage people not to consume factory farmed animals; to him, “‘slightly better’ isn’t good enough”.

“No animal who winds up in the factory farm production line has a good or even moderately good life.” – Marc Bekoff

Grandin’s retort is that without meat eaters, farm animals would have no life at all. She argues if animals are going to die anyway, it’s important to minimise their suffering.

Does this apply to humans too?

The New York Times once asked her if she’d consider helping to make capital punishment more humane. Her response was blunt.

“I have read things about the malfunctions of the electric chair… I know how to fix it, but I will not use my knowledge to have any involvement in that. I will not cross the species barrier to help kill people. Period.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Democracy is hidden in the data

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Threatened by Muslim extremists, boycotted by Western activists, Ayaan Hirsi Ali (1969—present) has literally put her life on the line to promote her ideals of rational thinking over religious dogma.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali is a Somali born Dutch American writer best known for her fierce criticism of Islam – the religion of her birth.

She sprung to international notoriety in 2004, when a Muslim extremist killed her Dutch filmmaker colleague Theo Van Gogh, knifing a hand written letter into his chest which called for Hirsi Ali to die next. The extremist targeted the pair for making a film mocking Islam’s treatment of women.

This brush with death only strengthened Hirsi Ali’s resolve to champion her ideals of enlightenment values over religious intolerance. She went on to author four books condemning Islamic teaching and practice.

Fluent in six languages, Hirsi Ali regularly travels the globe on speaking tours, skewering Islam and its local defenders in her articulate, charming style.

She doesn’t appeal to everyone though. The controversial writer has drawn the ire of Muslims and left wing groups who accuse her of anti-Islamic bigotry. Loathed by fundamentalists, she is forced to travel with armed security.

From believer to infidel

Hirsi Ali’s 2006 autobiography Infidel chronicled her extraordinary life journey from devout Somali child to Dutch politician to celebrity atheist intellectual.

Born to a Muslim family, Hirsi Ali says she was five years old when her grandmother ordered a man to undertake a female genital mutilation procedure on her. As a child, she was a believer who read the Qu’ran, wore a hijab and attended an Islamic school.

Looking back, the writer could see all that was wrong with her upbringing – violent beatings, unquestioning faith and rigid enforcement of gender roles.

Hirsi Ali says she sought asylum in the Netherlands in 1992 to flee her father’s attempt to arrange her marriage.

In her new home, the avid reader devoured the writing of enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire, Mill and Locke. These authors taught her to question blind faith and instead embrace science and rational thought.

After working as a translator and researcher, Hirsi Ali was elected to Dutch Parliament in 2002. She used her platform to criticise Islam and Muslim immigration.

Islam ‘is the problem’

Hirsi Ali holds the view that the problem with Islam is not simply a minority of extremists who give the religion a bad name:

“The assumption is that, in Islam, there are a few rotten apples, not the entire basket. I’m saying it’s the entire basket” – Ayaan Hirsi Ali

She argues violence is inherent in the core Islamic text and this is something most Muslims fail to recognise.

According to Hirsi Ali, Muslims can be categorised into three groups.

First, there are “Medina Muslims”, who seek to force extreme sharia law out of their religious duty.

Second, “Mecca Muslims”, are a majority of the faith who are devout but don’t practice violence. The problem with this group, says Hirsi Ali, is they fail to acknowledge or reject the violence in their own religious text.

The third group, “Muslim reformers”, explicitly reject terrorism and promote the separation of religion and politics.

Hirsi Ali argues this third reformer group must overcome the extremists to win the hearts and minds of a majority of Muslims.

Feminist hero or anti-Muslim bigot?

Ayaan Hirsi Ali was initially seen as a feminist activist who championed the cause of oppressed Muslim women. After moving to the US in 2006, she’s associated herself more with right wing groups than women rights’ activists. She became a fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute and a regular interviewee on Fox News.

Married to historian Niall Ferguson, the couple have been described as “the Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie of the intellectual right”.

She has also tweeted her support for Brett Kavanaugh, who was confirmed to the US Supreme Court despite allegations of past sexual assault.

Hirsi Ali’s right wing views and harsh criticism of Islam has seen Western activists target her alongside Muslim fundamentalists.

In 2014, Brandeis University in the US reversed its decision to award her with an honorary degree following objections from students.

In 2017, she cancelled a planned visit to Australia amid security concerns and a petition protesting her speaking appearance.

The Southern Poverty Law Center – a US advocacy group famous for defending civil rights – once categorised her as an anti-Muslim extremist.

Hirsi Ali says she can’t understand why she’s become the enemy:

“It has always struck me as odd that so many supposed liberals in the West take their side rather than mine … I am a black woman, a feminist and a former Muslim who has consistently opposed political violence”.

But if terrorists don’t deter her, activists have no chance. Hirsi Ali will continue to tread her dangerous path to promote what she believes are true liberal values.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

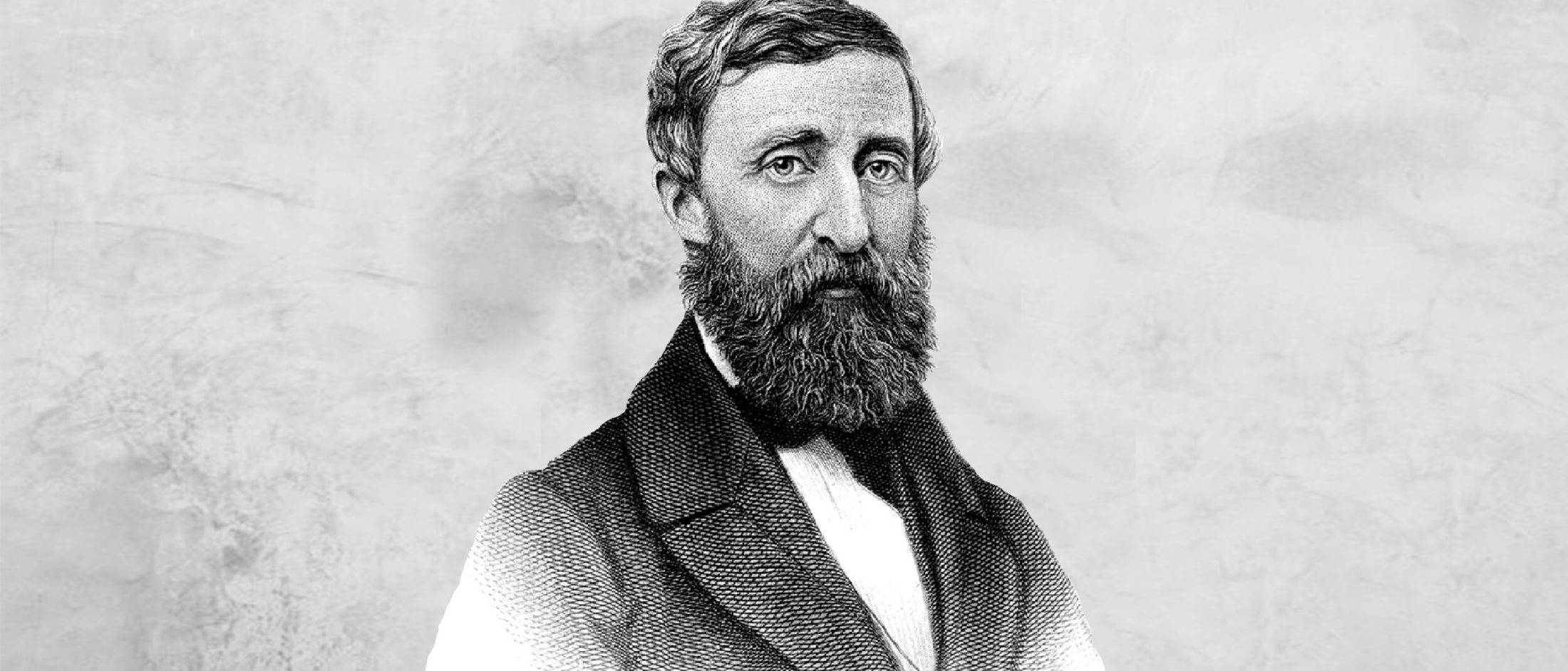

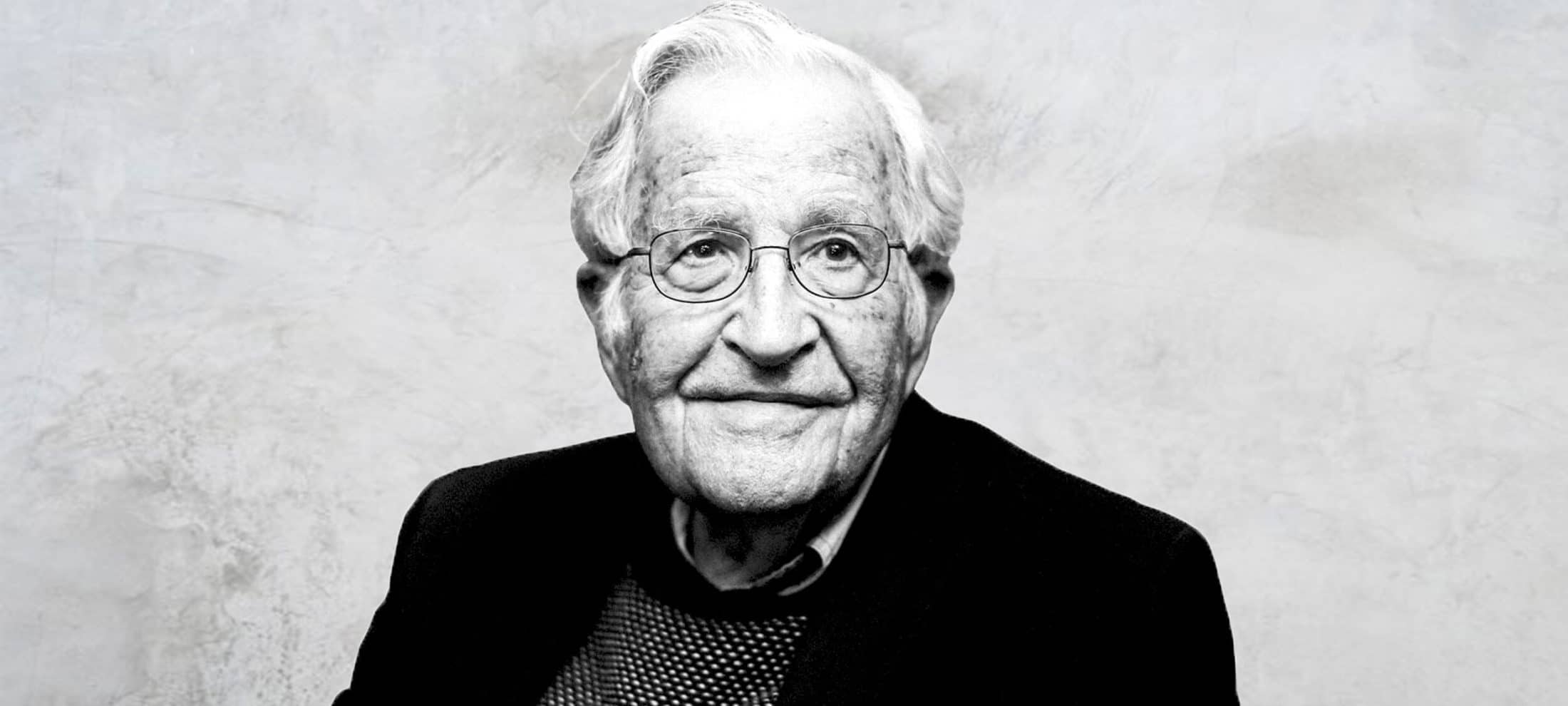

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 NOV 2018

Noam Chomsky (1928—present) is one of the foremost scholars and activists of our time.

With over a hundred books, thirty honorary degrees, and a generation of aspiring leftists behind him, Chomsky’s life puts a practical lens on the motto ‘protest is patriotic’.

The human tendency towards freedom

Chomsky earned a PhD in linguistics for his theory of “universal grammar”, a theory where all people are “born knowing” shared properties that underpin all human language. These properties, which create what he calls a “language acquisition device”, are what helps babies pick complex languages up instinctively.

According to Chomsky, while language’s laws and principles are fixed, the manner in which they are generated are free and infinitely varied. This view of human nature is one that runs through Chomsky’s attitudes to linguistics or politics: we must protect the innate human tendency towards freedom.

Pessimist of intellect

Chomsky’s opposition to war and totalitarianism started early. He wrote his first paper on the threat of fascism at ten. He opposed the Vietnam War while working at MIT, a military-funded university. He called Gaza the world’s “largest open-air prison” and said the US bears full responsibility for Israel’s war crimes.

Chomsky’s public denunciations of US foreign policy in Central America and East Timor, its interference in Middle Eastern elections and the shoot-first-ask-later’ type of diplomacy have drawn widespread ire and admiration. At the height of his fame in the 70s, it was discovered the CIA was keeping tabs on him and publicly lying about doing so.

Noam Chomsky’s consistent and vocal criticism of the US government comes from the belief that he, as a member of that country, holds a moral responsibility to stop it from committing crimes. That, and it’s far more effective than criticising a government that isn’t responsible for him.

“States are not moral agents; people are, and can impose moral standards on powerful institutions.”

Manufacturing consent

In what is arguably Chomsky’s most famous work, ‘Manufacturing Consent’, he outlined mainstream media’s complicity with government and business interests. He traced the capitalist formula of selling a product at a profit to the highest bidder in relation to the media. Here, people are the product and advertisers are bidding for our attention. Compare this with the monopoly social media has over our time and the ensuing competition for available ad space, and you’ll notice this line of argument growing in prescience.

Chomsky argued the advertising market is shaped by the external conditions of the state. It’s in their best interests to placate their ‘product’ and water down anything that would spur them to act against it. Any dissenting opinion is either ignored or presented as an anomaly. This is anti-democratic, said Chomsky, for a nation is only democratic insofar as government policy accurately reflects informed public opinion.

“If we don’t believe in free expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.”

Speak truth to power

Fred Halliday, an Irish academic, has criticised Chomsky for overestimating the power and influence of the US. Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, Oxford historian Stephen Howe, and linguist Neil Smith, have called him a fierce and aggressive moral crusader, who dismisses critics as unqualified, mistaken, or even “charlatans“.

Today, Chomsky is outspoken on what he considers the two greatest threats to humanity: nuclear war and climate change. But with NEG scrapped, the Doomsday Clock inching to midnight, and Congress split, it looks unlikely that decisive action against either of these threats will be carried out anytime soon.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

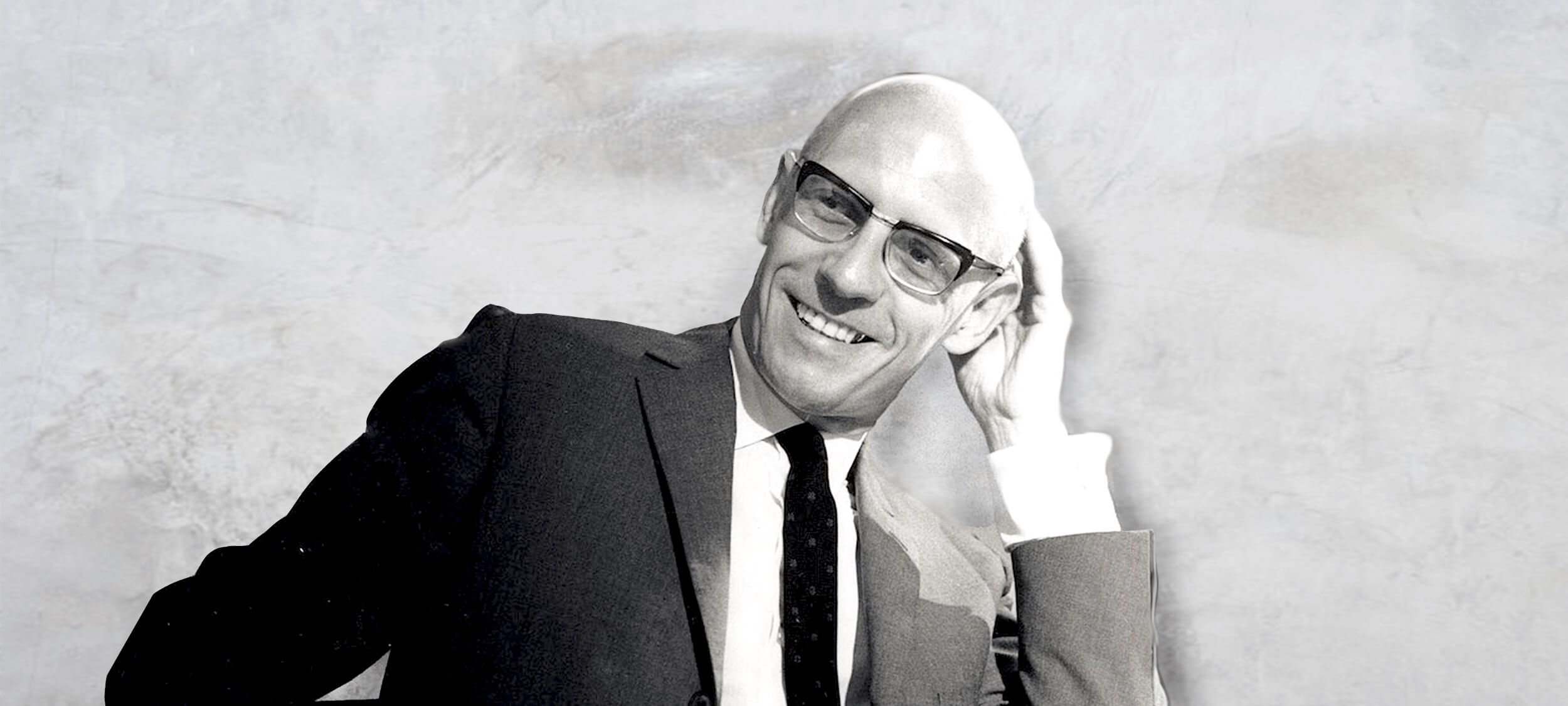

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 NOV 2018

Eleanor Roosevelt (1884—1962) was an American diplomat and longest serving First Lady of the United States, best known for her work on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

She was affectionately dubbed “The First Lady of the World”. The thread running through her massive body of work is the single idea: fear threatens our lives and our democracies.

To live well means to live free from fear

Roosevelt lived in a world reeling from fascism. Though the Second World War had ended, the horrors of Nazism, the Holocaust and Stalinism revealed the depths people would succumb to out of fear and insecurity.

It wasn’t your garden variety type of fear she was concerned with. It was the type of widespread fear that debilitates courage, rewards conformity and stifles “the spirit of dissent”. By succumbing to this immobilising fear, Roosevelt said, we waste our lives.

“Not to arrive at a clear understanding of one’s own values is a tragic waste. You have missed the whole point of what life is for.”

Roosevelt wanted all people to know their values. As an influential public figure and patriotic American, she especially wanted this for her country.

This wasn’t without reason. The growing fear of political others (McCarthyism) and racial others (the push for segregation) mobilised Roosevelt and emboldened her stance. She didn’t want conformity to win.

“When you adopt the standards and the values of someone else or a community or a pressure group, you surrender your own integrity. You become, to the extent of your own surrender, less of a human being.”

Find a teacher in every person you meet

Roosevelt felt the danger of fear and conformity went beyond the trauma of war. It could quash “a spirit of adventure”, a way of viewing and experiencing everyday life that made you a better person.

She wasn’t talking about a thrill seeking, you-only-live-once, way of navigating the world. She meant close mindedness – denying your life experiences the opportunity to change your mind and mould your actions.

“Learning and living are really the same thing, aren’t they? There is no experience from which you can’t learn something. When you stop learning you stop living in any vital or meaningful sense. And the purpose of life is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear for newer and richer experience.”

Roosevelt believed that everyone has something to teach you, and you are the ultimate beneficiary. Your character, your actions and your democratic polity.

And some might find being motivated by self-betterment alone to be selfish. After all, shouldn’t we do good simply because it is good? Isn’t it more noble to be motivated by what Kant called “good will”, or a moral duty?

Even if it’s possible that realizing motivation from a place of moral obligation is a higher ideal, Roosevelt was grounded in the everyday. She wasn’t concerned with principles the vast majority of a traumatised, distrustful nation would find out of reach, so she focused on the individual.

A principled life

The most remarkable thing about Roosevelt aren’t necessarily her ideals. It was her moral gumption to act on them even if they were unorthodox for the times or grossly unpopular.

She lobbied for greater intakes of World War II refugees when immigration was not supported by many Americans still reeling from the hardships of the Great Depression. She criticised her husband, President Franklin Roosevelt, for a policy intended to address the post-Depression housing market crash that segregated black and white citizens.

She broke with tradition by inviting African American guests to the White House. She spoke out against the internment of Japanese soldiers to the very population grieving the 2403 Americans they killed at Pearl Harbour (in comparison, it’s reported 55 Japanese lives were lost).

Roosevelt’s reputation for loving all has not gone unchallenged. She has been accused of taking sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a way that contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights she worked on. While famous for wanting to protect displaced post WWII refugees, who were often Jewish, she felt the solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict was to resettle indigenous Palestinians in Iraq – the suggestion being she had a Zionist bias.

Roosevelt nevertheless maintains her name as a pioneer in humanitarian efforts who walked her talk. Fast forward to today’s polarised political spectrum, and her story reminds us the tools to make it through are there.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2018

It’s no exaggeration to say the ideas of Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith (1723—1790) have shaped the world we live in.

By providing the core intellectual framework in defence of free markets, he positioned human liberty and dignity at the centre of trade and money – all for the common good.

Adam Smith, the pioneer

In the 18thcentury, the race to colonise as many resource rich places as possible meant powerful countries were often at war. Companies which added to the wealth of empires were protected by grateful governments, creating trade monopolies that seemed impossible to dismantle. This was the heyday of mercantilism.

Smith noticed how these actions created concentrations of wealth, benefiting the wealthy while the labour class struggled to survive. His first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, argued that the virtues of sympathy and reciprocity could tame greed.

His second, The Wealth of Nations, was about promoting a new way of approaching wealth that was as lucrative as it was just. The approach Smith adopted was multifaceted: economic, defensive, legal, and moral.

Smith argued that countries were competing for the wrong thing. Wealth wasn’t to be found in commodities like gold and silver. It resided in human labour and ingenuity. Smith encouraged countries that would normally look externally for wealth, suppressing the labour class and enslaving others, to look internally instead.

If the labour class could have the freedom to pick their job, all the while knowing the government would leave the money they made well alone, why wouldn’t they work hard at it? They would produce goods and services of even higher quality, and the government could buy these and trade them with each other. Everyone wins.

Collaboration would mean countries wouldn’t need to waste money on defence and war. They could save and accumulate capital, and invest that into better machinery, freeing people to work more productively. The labour class would grow richer, and so would the nation.

Smith stressed that in order for a free market to ensure fair pay for fair work, contracts had to be honoured, people had to keep their word, and governments mustn’t get into debt or take people’s property. Theft, negligence, mistakes, or irresponsible government spending must to be managed by the rule of law. And in the case of foreign powers, defence.

Thus, for Smith – a free market must rest on a sound ethical foundation. Given this, he argued for moral education of a kind that would lead people to be honourable and behave justly. This included the rich. Smith thought that an appeal to ‘enlightened’ self-interest might lead them to act honourably. By lavishing praise, accolades, and rewards on those who spend their wealth in charity, the rich gain the status and rank they really desire.

Adam Smith, the legacy

Claims of plagiarism, usury, inconsistency, racism, and all else aside, the major complaint directed towards Smith is his concept of the “invisible hand”. His observation that self-interested individuals end up benefiting the common good – that they are “led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention.” – has prompted some critics to label him naïve, idealistic, or even immoral.

The following quotation (misattributed to John Maynard Keynes) sums it up: “Capitalism is the astounding belief that the wickedest of men will do the wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone”. But that plays into the Smith = laissez-faire trap, and ignores the safeguards he proposed against human corruption.

Smith did not think greed was good, saying this removed “the distinction between vice and virtue”, nor did he believe business interests and the public interest necessarily coincide. Instead, his perspective was that market competition forced people to act in ways that benefited others, regardless of their intention. And when it failed to do that, an overarching authority should step in. For Smith, markets have no intrinsic value – they are merely tools for the betterment of life for all.

No doubt the world we live in now is vastly different to pre-Industrial Scotland. Mass media, the Internet, the textile industry, factory farms, surveillance, housing prices, offshore tax havens…much would have seemed strange and unfamiliar to Smith. But his work and legacy leave a lesson in economics, ethics, and politics – all the more prescient in a world where the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 20 AUG 2018

Feminist firebrand or second wave scourge? When The Female Eunuch was published to international success, it was obvious Germaine Greer (1939—present) had hit a nerve – something she continues to do.

This article contains language and content that may be offensive to some readers.

Germaine Greer is an Australian writer and public intellectual who rose to international influence with her book published in 1970, The Female Eunuch. It was a watershed text in second wave feminism, a bestseller around the world, and it made Greer a household name.

Greer’s infamously bold voice and sense of humour permeates throughout the book. Her strong character and take no prisoners approach to public debate saw her regularly contribute to panels and broadcast media. Greer was launched into the public eye as a young, bolshie feminist star.

Since then, Greer has written many books spanning literature, feminism and the environment. She has become one of Australia’s most ‘no-platformed’ thinkers. Almost five decades on, we take a look at her contributions to feminist philosophy.

Human freedom is intrinsically tied to sexual freedom

Greer is a liberation, rather than equality feminist. She believed achieving true freedom for women meant asserting their uniquely female difference and “insisting on it as a condition of self-definition and self-determination”.

Greer wanted to be certain about this female difference, and for her, this certainty started with the body.

You can think of Greer’s claims like this:

- Women are sexually repressed.

- Men are not sexually repressed.

- The difference between men and women is their biological sex.

- Biological sex determines if you’re sexually repressed or not.

The second part of her argument is as follows:

- Women are expected to be ‘feminine’.

- Women are sexually repressed.

- The expectation to be ‘feminine’ is sexually repressive.

Greer is scathing in her portrayal of ‘femininity’. She claimed it kept women docile, repressed, and weak. It stifled women’s sexual agency, hence the ‘eunuch’, which was intrinsically tied to their humanity.

Only by liberating women sexually could they remove this imposed submissiveness and embrace the freedom to live the way they wanted.

“The freedom I pleaded for twenty years ago was freedom to be a person, with dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood. Freedom to run, shout, talk loudly and sit with your knees apart.” – Germaine Greer (1993)

A feminist utopia is an anarchist utopia first

In the London Review of Books 1999, Linda Colley wrote, “Properly and historically understood, Greer is not primarily a feminist. More than anything else, she should be viewed as a utopian.”

For Greer, the greatest danger of the widespread female eunuch is not an unfulfilling sex life. It is in her being so concerned with femininity that she is incapable of political action. Greer believed this social conditioning was dire and its enforcers so embedded that revolution rather than reform was required.

Greer called for this revolution to start in the home. She spoke openly about topics that at the time were taboo: menstruation, hormonal changes, pregnancy, menopause, sexual arousal and orgasm. She decried the agents of femininity that she felt kept women trapped: makeup, constricting clothing, feminine hygiene products, stifling marriages, misogynistic literature and female sexual competitiveness. She reserved her greatest fury for widespread consumerism, which she believed kept women dependent on the systems that forged their own oppression.

Like Mary Wollstonecraft before her, Greer argued neither men nor women benefited from this. She called upon women to rebel again these “dogmatists” and create a world of their own. But the solution she presents is exploratory instead of pragmatic. Perhaps women could live and raise their children together, making their own goods and growing their own food. It would be somewhere pleasant like the rolling landscapes of Italy, with local people to tend house and garden. (It’s unclear whether these local people would be liberated too.)

Intellectual criticisms

Greer’s celebration of non-monogamous sex in The Female Eunuch and her derision of Western society’s obsession with sex in Sex and Destiny led critics to label her ideas slipshod and too inconsistent for a public intellectual.

The root of most criticisms and controversies surrounding Greer, tend to stem from her view of the sexes. Like other second wave feminists, she suggested biological sex determined women’s oppression. This stands in stark contrast to the perspectives of third wave feminists and queer theorists, such as Judith Butler, for whom gender’s learned behaviours play the crucial role.

Greer and her contemporaries are often criticised by third and fourth wave feminists for predicating their philosophies on a male/female binary. A binary that does not account for the broad chromosomal spectrums found among intersex people or the many ways in which individuals feel and express their gender.

Infamous commentary

Greer is not the docile feminine woman she warned of in The Female Eunuch. She has long been celebrated for bucking trends and being refreshingly bold and frank. She is also heavily criticised for being rude, offensive and out of touch. She has been described as having “the self-awareness of a sweet potato”, a “misogynist”, and “a clever fool”.

After she extolled the work of Australia’s first female Prime Minister Julia Gillard on an episode of ABC’s Q&A, she was slammed for criticising Gillard’s body and clothing:

“What I want her to do is get rid of those bloody jackets … They don’t fit. Every time she turns around you’ve got that strange horizontal crease which means they cut too narrow in the hips. You’ve got a big arse Julia…”

Social media lit up with calls for Greer to “shut up” after she linked rape and bad sex in the age of #MeToo:

“Instead of thinking of rape as a spectacularly violent crime – and some rapes are – think about it as non-consensual, that is, bad sex. Sex where there is no communication, no tenderness, no mention of love. We used to talk about lovemaking.”

It is probably Greer’s public statements around transgender women that have attracted the most protest. In an interview after an intense no-platforming campaign to cancel a lecture Greer was scheduled to give at Cardiff University on women and power in the 20th century, she said, “Just because you lop off your penis and then wear a dress doesn’t make you a fucking woman”.

This sentiment probably links with Greer’s ideas on sexed bodies. A sympathetic reading of the comment might see it as one about being born into oppression – a rather second wave feminist sentiment that echoes the racial and queer politics of the same era. An idea that’s sometimes cited as analogous to Greer’s controversial comment is that you cannot understand what it is to be black, unless you were born black and experienced discriminations since the day of your birth. Perhaps she was suggesting we cannot understand the oppression experienced by women and girls unless we are born into a female body. Perhaps not. Either way, the comment was received as incredibly offensive and naive to transgender women’s experiences.

“People are hurtful to me all the time. Try being an old woman. I mean for goodness sake! People get hurt all the time. I’m not about to walk on eggshells.” – Germaine Greer, 2015

Greer and second wave feminists generally are at odds with intersectional feminism which is prominent today. Intersectional feminism holds that many factors beyond sex marginalise people – age, race, nationality, disability, class, faith, sexual orientation, gender identity… Different women will be oppressed to varying degrees.

Whether Greer is a trailblazer or tactless provocateur, it is doubtless her ideas have influenced the political and personal and landscapes of gender relations and feminist thinking.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 JUL 2018

Women’s oppression comes down to biological differences – so get rid of them. If you can put a man on the moon, you make a mechanical womb and gestate a baby without a woman.

These were the arguments of Shulamith Firestone (1945—2012), writer, artist and feminist, whose book, The Dialectic of Sex, argued the structure of the biological family was primarily to blame for the oppression of women.

With a radical and uncompromising vision, she advocated for the development of reproductive technologies that would free women from the responsibilities of childrearing, dismantle the hierarchy of family life, and set the foundations for a truly egalitarian society.

The girlhood of a radical thinker

Firestone was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in Ottawa, Canada in 1945. Her mother was a Holocaust survivor that came from a lineage of rabbis and scholars, and her father was a travelling salesmen.

Firestone possessed a fierce intelligence and strong will from a young age and regularly came into conflict with the stringent gender norms that her religious father imposed. When she questioned why she had to make her brother’s bed in the morning, her father replied, “because you’re a girl.”

In the late 1960s, Firestone left home to study art in Chicago and then New York, where she joined left wing political movements and came of age intellectually. While she was free from her father’ tyranny, she saw the same sexism that had controlled her life at home across all areas of society. It was a time when women held almost no major elected positions, abortion was illegal, rape a stigma to be borne alone, and home making seen as a woman’s highest calling.

As a response to this, Firestone began studying history and feminist literature, hoping to understand the root cause of women’s oppression, which resulted in the publication of The Dialectic of Sex in 1970.

The Dialectic of Sex

While other feminist writers and philosophers proposed that the cause of women’s oppression was, at root, political and cultural, Firestone made a radical departure, positing that the inequality between men and women stemmed from fundamental biological differences – most notably that women had to carry, give birth to, and nurse babies.

This biological reality, Firestone argued, created an “unequal power distribution” within families. Because women were responsible for a child’s care, they became dependant on men to provide for them while they were unable to leave the home. This in turn gave rise to a hierarchy within the family in which babies were dependant on mothers, mothers on their husbands, and husbands on no one.

Firestone argued that over the course of human history, society itself had come to mirror the structure of the biological family and was the source from which all other inequalities developed.

Women were expected to stay at home and care for children, which held them back from becoming financially independent and achieving political agency.

If the feminist movement was to overcome male domination, it had to reckon with the fundamental biological reality that underpinned it.

“The end goal of feminist revolution must be… not just the elimination of male privilege, but of the sex distinction itself.”

While questioning the fundamental biological conditions was not conceivable in previous centuries, Firestone said the great advancements that had accrued in science and technology in the 20th century made it possible to imagine a future in which the reproductive role of women was outsourced to “cybernetic machines”. She believed if the same energy and resources were put into developing reproductive technologies as had been put into other projects, like sending a human to the moon, then it could be achieved in decades.

What held this research back, Firestone suggested, was institutional resistance from men in positions of power who did not want to disrupt the existing hierarchy.

“The problem becomes political … when one realises that, though man is increasingly capable of freeing himself from the biological conditions that created his tyranny over women and children, he has little reason to want to give this tyranny up.”

The true feminist cause, then, was to demand reproductive technology that could free women from what had previously been a biological destiny. Firestone believed if this was achieved, and reproduction was no longer the sole responsibility of women and their bodies, the family would undergo a radical restructuring, a flattening of the patriarchal hierarchy, which would then be mirrored in a more egalitarian society itself.

Brilliant and preposterous

The Dialectic of Sex caused a stir from the moment it was published. It was hard for critics to deny Firestone’s prodigious intellect, but they wrote off her ideas as too radical, too utopian, and too ridiculous to warrant serious engagement. Her theory of gender inequality was called “brilliant” and “preposterous” in the same review by one New York Times critic.

The book’s publication caused a greater rift between Firestone and her family, and her staunch line on biological inequality alienated her from some feminist groups. By the 1980s, when the backlash against radical feminism had taken hold of mainstream American culture, Firestone retreated to a small apartment in Manhattan where she spent her days painting in isolation. She was found dead in August 2012 at the age of 67.

In the 50+ years since Firestone published The Dialectic of Sex, we have seen enormous and rapid technological developments in many areas, and yet reproductive technologies like artificial wombs are still seen as an unlikely and unwanted science from a dystopian sci-fi future. Our culture, for the most part, still associates artificial wombs with the 1932 novel Brave New World, in which Aldous Huxley imagined a future where foetuses are grown in “bottles” in vast state incubators. For Huxley, the idea of severing the biological tie between mother and child was the centrepiece of his dystopian vision, the essential metaphor of a society that had become ethically set adrift.

Reading Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex – a brilliant, passionate and uncompromising book – forces us to confront that the way technology progresses is informed by political motivations, and that science is not neutral, but can be used to reinforce and perpetuate unequal distributions of power.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

“The pen would smoothly write the things it knew, but when it came to love it split in two, a donkey stuck in mud is logic’s fate – Love’s nature only love can demonstrate.” – Rumi

Rumi (1207—1273) has long been recognised as one of the most important contributors to Islamic literature and Sufism, the spiritual and mystic element of Islam. His enormous collection of mystical poetry is considered among the best that has ever been produced. His seminal text is the Masnavi, a six book poem written in rhyming couplets. It is so revered as an expression of Godly knowledge that it is referred to as “The Koran in Persian”.

What is Sufism?

To understand Rumi, you need to understand Sufism. It is often misrepresented as a sect, school, or deviant form of Islam but is better described as a distinct stream in Islamic spirituality. Sufism was first embodied by Muhammad and his early followers, then medieval scholars like Abu Hamid Al-Ghazzali, Ibn Arabi, and of course, Rumi.

Sufism is characterised by its focus on moral cultivation and establishing a personal connection to God through reforming, disciplining, and purifying the ego. It seeks to attain this intuition of God through disciplines that practice an austere lifestyle known as ascetism. One example of this is dhikr, a form of worship where you become absorbed in rhythmic repetitions of God’s name.

Sufism seeks a type of knowledge outside worldly intellect – one that is intuitive and is inextricably tied to the Divine.

Life of Rumi

Rumi, known in Iran and Central Asia as Mowlana Jalaloddin Balkhi, was born in 1207 in the province of Balkh, which is now the border region between Afghanistan and Tajikistan. His family left when he was a child shortly before Genghis Khan and his Mongol army arrived. They settled permanently in Konya, central Anatolia, which was formerly part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Rumi was probably introduced to Sufism through his father, Baha Valad, a popular preacher who also taught Sufi piety to a group of disciples.

The turning point in Rumi’s life came in 1244 when he met a wandering Sufi in Konya called Shamsoddin of Tabriz. Shams, as he was most often referred to by Rumi, taught him the most profound levels of Sufism, transforming him from a devout religious scholar to an ecstatic mystic.

Rumi died on 17 December 1273 shortly after completing his work on the Masnavi. His passing was deeply mourned by the citizens of Konya, including the Christian and Jewish communities. His disciples formed the Mevlevi Sufi order and named it after Rumi, whom they referred to as ‘Our Master’ (which translates to Mevlana in Turkish and Mowlana in Persian). They are better known in the West as the Whirling Dervishes, because of the distinctive dance they now perform as one of their central rituals.

Rumi’s death is commemorated annually in Konya, attracting pilgrims from all corners of the globe and every religion. The popularity of his poetry has risen so much in the last couple of decades that the Christian Science Monitor identified him as the most published poet in America in 1997 and UNESCO declared 2007 to be the Year of Rumi.

Overvaluing intellect

Rumi, like most Sufis, praised the intellect and considered its refinement a religious imperative. But he was clear about the types of knowledge he believed it could sufficiently possess. He considered o domain the sentimental and material world, not the theoretical and metaphysical one.

Rumi’s caution was this: when one relies solely on their own intellect to understand Being and Reality, they risk confining their understanding to a mortal and ultimately finite resource – themselves. He regarded it a folly of the ego to believe one’s intellect limitless and warned against reducing God to abstract puzzles in order to maintain that belief. Rumi scorned placing the intellect too high and pursuing knowledge for knowledge’s own sake.

“He knows a hundred thousand superfluous matters connected with the (various) sciences, (but) that unjust man does not know his own soul.

He knows the special properties of every substance, (but) in elucidating his own substance (essence) he is (as ignorant) as an ass.” – Rumi

The transcendence of man

So, if intellect isn’t enough, what is? Rumi would say, ‘Divine love.’

This divine love can also be translated as grace or friendship with God. In the Islamic worldview, humanity is unique in its capacity to autonomously know God, and this gives people an honoured status. Even so, no human can achieve divine love out of their own efforts. They can only be granted it.

Rumi was of the view that seeking essential knowledge – knowledge about the essence of humanity – was a way one might be granted divine love. It was the best type of knowledge, because it was tied to questions of meaning, purpose, and death. In other words, knowing yourself was a means of knowing God.

According to the Sufis, knowledge of God comes in three levels: material, conceptual, and experiential. Think of it as the different between knowing an apple exists, reading a detailed Wikipedia page about it, and eating one in the flesh. All three are different forms of knowing what an apple is – but each deepens in understanding. The last level is transformative in a way the other two are not. Try explaining what an apple tastes like to someone who has never had one. You may come very close, but they will never know what you mean unless they take a bite themselves.

Likewise, the Sufis believed that the highest knowledge of God was something that could only be experienced. To read and contemplate upon God or the universe was one thing. But experiencing God was something totally different, something impossible to intellectualise.

Rumi believed manifesting the four virtues – courage, wisdom, and temperance, which when balanced, lead to perfect justice, the fourth virtue – would lead to some form of transcendence above the hubbub of life’s claims and counterclaims. But when every human being’s views cannot be divorced from their experience, how was this possible?

For Rumi, this highlighted humanity’s dependence on God. Only a friend of God, or Wali, could be objective enough to see truth and loving enough to be just.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

Confucius (551 BCE—479 BCE) was a scholar, teacher, and political adviser who used philosophy as a tool to answer what he considered to be the two most important questions in life… What is the right way to rule? And what is the right way to live?

While he never wrote down his teachings in a systematic treatise, bite sized snippets of his wisdom were recorded by his students in a book called the Analects.

Underpinning Confucian philosophy was a deeply held conviction that there is a virtuous way to behave in all situations and if this is adhered to society will be harmonious. Confucius established schools where he gave lectures about how to maintain political and personal virtue.

“It is virtuous manners which constitute the excellence of a neighborhood.”

His ideas set the agenda for political and moral philosophy in China for the next two millennia and are emerging once again as an influential school of thought.

Humble beginnings

Confucius was born in 551 BC in a north-eastern province of China. His father and mother died before he was 18, leaving him to fend for himself. While working as a shepherd and bookkeeper to survive, Confucius made time to rigorously study classic texts of ancient Chinese literature and philosophy.

At the age of 30, Confucius began teaching some of the foundational concepts he formulated through his studies. He developed a loyal following and quickly rose up the political ranks, eventually becoming the Prime Minister of his province.

But at the age of 55 he was exiled after offending a higher ranking official. This gave Confucius an opportunity to travel extensively around China, advising government officials and spreading his teachings.

He was eventually invited back to his home province and was allowed to re-establish his school, which grew to a size of 3000 students by the time he died at age 72.

The golden age

Underpinning much of Confucius’ thought was a belief that Chinese society had forgotten the wisdom of the past and that it was his duty to reawaken the people, particularly the young, to these ancient teachings.

Confucius idealised the historical Western Zhou Dynasty, a time, he claimed, when living standards were high, people lived and worked in peace and contentment, the leaders carried out their duties in accordance with their rank, and the social order was stable and harmonious.

Confucius devoted his life to teaching the wisdom of this ancient society to his contemporaries in the hope of reinventing it in the present. For this reason, he didn’t claim to be an original thinker, but a receptacle of past wisdom. “I transmit but do not innovate”, he said.

Dao, de, and ren

While Confucius never wrote a systematic philosophical treatise, there are three intertwined concepts that run through his philosophy: Dao, De, and Ren.

Dao: Confucius interpreted Dao to mean a Way of living, or more specifically the right Way of living. This was not a concept he made up. It was already a central part of Chinese belief systems about the natural order of the universe. Dao is a slippery but profound concept suggesting there is a singular Way to live that can be intuited from the universe, and that all of life should be directed towards living this Way. If the Way is followed, the individual and society will be in perfect harmony.

De: Confucius saw De as a type of virtue that lay latent in all humans but that had to be cultivated. It was the cultivation of this virtue, Confucius believed, that allowed a person to follow the Way. It was in family life that people learned how to cultivate and practice virtuous behaviours. In fact, many of the main Confucian virtues were derived from familial relationships. For example, the relationship between father and son defined the virtue of piety and the relationship between older and younger siblings defined the virtue of respect. For this reason, Confucian ethics did not leave much room for an individual to exist outside of a family structure. Knowing where you stood in your family and your society was key to living a virtuous life.

Ren: While most Confucian virtues were cultivated within a strict social and family structure, ren was a virtue that existed outside this dynamic. It can be translated loosely as benevolence, goodness, or human-heartedness.

Confucius taught that the ren person is one who has so completely mastered the Way that it becomes second nature to them. In this sense ren is not so much about individual actions but what type of person you are. If you perform your familial duties but do not do so with benevolence, then you are not virtuous. Ren was how something was done, rather than the act itself.

Contemporary influence and relevance

Confucius’ influence on Chinese society during his life and in the two millennia since has been enormous. His sound bite like philosophies became China’s handbook on politics and its code of personal morality.

“He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.”

It wasn’t until Mao’s Cultural Revolution that some of the basic tenets of Confucian ethics were publicly denounced for the first time. Mao was future oriented and utopian in his politics, and so Confucius’ idea of governance and ethics based in the ancient classics was considered dangerous and subversive. In fact, Mao’s Red Guards referred to the old sage as “The Number One Hooligan Old Kong”.

But in the past decade, the Communist Party has realised Confucius’ teachings might be useful again. The surge of wealth that has accompanied free market capitalism in China has meant that many of Mao’s ideologies no longer make sense for the government. This has prompted a resurgence of State led interest in Confucius as an alternative ideological underpinning for the current government.

While this is seen by many as a way for China to build a political future based on its philosophical past, others feel that the Communist Party has emphasised Confucian ideas about hierarchical social structure and obedience, while sidelining notions of virtue and benevolence.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Brother is coming to a school near you

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships