Space: the final ethical frontier

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 24 SEP 2020

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant once famously said “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and the more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within.”

It probably didn’t occur to Kant that there would come a day when the moral law and the starry heavens would find themselves in a staring contest with one another. In fairness though, it’s been almost 250 years since he wrote that quote. Today, those starry heavens play an increasingly important role in human affairs. And wherever there are people making decisions, ethical issues are sure to follow.

To get to know this final ethical frontier, I had a chat with Dr Nikki Coleman, Senior Chaplain Ethicist with the Australian Air Force. Nikki is a bona fide space ethicist to help us get up to (hyper) speed with all the new issues around ethics in space.

Is space an environment?

One of the largest contributions of the field of environmental ethics has been to encourage people to consider the environment as having value independent of its usefulness to humans. Before environmental ethics emerged as a field, many indigenous cultures and religions had already embedded these beliefs in the way they lived and related to land.

“The idea of space is that it’s a ‘global commons’,” says Coleman. “It belongs to all of us on the planet, but also to future generations. We can’t just dump space debris. We have to be careful about how we utilise resources. Like the resources on Earth, these resources are finite. They don’t go on forever,” she says.

This echoes one of the most common arguments about preservation and sustainability. We take care of the planet not just for ourselves, but for future generations. The challenge is helping people to understand that custodianship of space means thinking about the long tail on the decisions we make now. In fact, it might be even more difficult when it comes to space because, well, space is big, and it’s a long way away and we’ll likely never go there ourselves.

“What happens in space is the same as what happens on Earth, but it’s more remote,” Coleman tells me. And yet, despite this, what happens in space affects us profoundly. Just as we rely on trees, ecosystems and other aspects of the natural environment, we are reliant on parts of space as well. “Even though these objects feel further away from us, we still have an interdependency and a relationship with space,” explains Coleman.

What role should private companies play?

We’ve seen a lot of noise about space being made by private companies like SpaceX and Virgin – which is an enormous change from the time when travelling to space was something you could only do from a national space agency in a wealthy nation. But these companies have very different motivations for expanding into space.

“Space,” says Coleman “has become a very congested space.” “The cost of space operations has dramatically decreased, and we’re now seeing whole organisations devoted to their own space operations rather than as part of a government.”

This is where some issues can arise, “because what’s appropriate for a commercial operator in returning profits to stakeholders is not necessarily what’s appropriate for the whole of the planet.” Space is a ‘global commons’, it should be used to serve everyone’s interests – including future generations – not just the needs and wants of a single company or nation. It’s unclear to what extent commercial operators are taking the idea of a global commons seriously.

“We have someone like Elon Musk putting a car into space – which is the ultimate litter – or talking about putting 42,000 satellites into low-earth orbit, which obviously creates problems around congestion and space debris,” Coleman explains, referring to Elon Musk’s proposed ‘Starlink’, a network of satellites that could dramatically improve broadband speeds.

The interstellar garbage dump

Space debris is a big deal. We probably all remember in primary school learning about how different parts of a rocket break apart as they launch into space. Some of that burns up in the atmosphere, but lots of it remains in orbit. And it’s not just a few parts of rockets and a random Tesla. There is a lot of junk floating around in orbit around earth.

“Why that is problematic is it actually stays there for a really long period of time,” Coleman explains. “Some of it will decay in orbit and burn up in the atmosphere, but a lot of it could stay there for tens of thousands of years.”

But it’s not just that the debris sticks around. It’s that it can wreck a whole lot of important stuff whilst it orbits around the planet.

Coleman tells me that debris can interfere with our current satellites. ”The International Space Station is actually quite vulnerable. It only takes a small puncture to make it a life-threatening situation. And the issue is growing because we’re putting more and more satellites – including small satellites that don’t manoeuvre – into space.”

The worst-case scenario when it comes to space debris was depicted in the recent film Gravity, where the debris destroys satellites, generating even more space debris in a cascading process called Kessler Syndrome.

“The idea of having a whole area of space that is full of space debris will actually have massive impacts for the future,” Coleman warns. We use satellites for so many things: communication, food security, navigation… it’s not just about posting on Twitter and putting photos on Facebook.”

“The precursor for space debris is lots of things in space, so that’s why it’s problematic when someone talks about putting tens of thousands of satellites into orbit.”

The militarisation of space isn’t new

Coleman is quick to point out that space and the military have a long history. In fact, Sputnik was a Russian military satellite, which means “we have had a militarisation of space operations right from the get go.”

However, there are some changes in the way that militaries are thinking about space today. “Currently, military operations in space predominantly look at satellites and communication and dedicated military satellites for example, we’re with starting to see an increase in aggressive uses of military uses of space,” says Coleman.

The challenges here are myriad, but one significant one is that so much of what’s up in space is infrastructure that both civilians and the military need. Usually, the law and ethics of war don’t permit the targeting of infrastructure used by civilians when that would be disproportionately harmful to them.

“I would argue that a civilian satellite is not a legitimate target because it could have catastrophic effects for the civilians that rely on that satellite.”

“Space debris is climate change 2.0”

Ok, yes, we already talked about space debris but it’s so interesting we have to do it twice. See, space debris isn’t just garbage; it’s property.

“If you throw a bottle into the ocean, anyone can pick that up. That means that all the plastic in the middle of the ocean can actually be collected and recycled and made into something commercially viable,” Coleman explains. “But everything that goes into space is actually the property of the country that launched it.”

This means even if someone wanted to tidy up space, they couldn’t. Anyone can litter the global commons, but that doesn’t mean anyone can tidy it up. The rubbish belongs to someone.

This is where Coleman sees the analogy to climate change beginning. No one person or group can solve the problem. “We need to work together internationally to search to solve the problem of space debris,” she says. “I’m really excited that at the moment there is a large amount of discussion internationally about climate change, but there isn’t a lot being done around [space debris].”

The other, more frightening, climate change analogy is in terms of the threat posed by space debris. “It has the capacity to have a much faster impact on life on the planet,” says Coleman. “It could push us back to the 1950s.”

If there’s life on Mars, can we live there?

It seems interesting that at a time when many societies are coming to grips with the harms and problems colonisation has had around the world, there are people seriously contemplating the colonisation of Mars. For Coleman, this reveals one of the central ethical questions – not just for space, but in any walk of life. How far do our moral obligations extend?

“Do we have a duty not just to ourselves but to others as well, and do we have a responsibility to future generations of humans or potentially future generations of whatever is growing on Mars?”

We accept that we have obligations to future humans, but it seems quite different to say that we have obligations to a microbial life form on Mars. However, Coleman poses a further question: do we also have duties to whatever that microbial organism might evolve to be in millions of years?

“If we find life, do we owe it the opportunity to grow and develop into something that might eventually turn into intelligent life?”

I, for one, welcome our new microbial brothers and sisters.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Longtermism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Big thinker

Climate + Environment

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 SEP 2020

At TEC, we firmly believe ethics is a team sport. It’s a conversation about how we should act, live, treat others and be treated in return.

That means we need a range of people participating in the conversation. That’s why last year, we asked for funding support to bring another philosopher into our team. Thanks to our donors, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Eleanor Gordon-Smith as a Fellow. Already established as one of Australia’s leading young thinkers, Eleanor is a published author, broadcaster and in demand speaker. She’s also currently reading for her PHD at Princeton University. To welcome her on board and introduce her to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat with her.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

I remember sitting in my first philosophy class and feeling like this was what thinking should really be like. I left knowing less than I thought I did when I arrived – all my other classes were about the legislative agenda around human rights and my philosophy class said wait, what’s a right and what counts as human? I loved the ability to ask those questions and from that day on it’s always felt like that’s where the real action is: the deep questions that we too easily take for granted.

Do you specialise in a key area or areas?

I cross-specialise in ethics, language, and epistemology [the study of knowledge]. In all three areas I am interested in the powers we can only have because we are social creatures. I work on moral powers that we can only exercise in social settings – such as consent, and promise – how linguistic meaning can be constructed and destroyed by social relationships, and how being embedded in societies can facilitate or disrupt our processes of gaining knowledge. The uniting theme across my work is that we depend on each other for many of our most important abilities and powers, such as speaking, learning, or coming up with moral frameworks, and yet a lot of the time other people are very bad. So what are we to do, if we rely on each other for our most foundational abilities but frequently “each other” is the source of our problems? So far I only have the question. But that’s where all good philosophy starts…

Sounds like a phenomenal place to start. Now let’s have a fan-girl moment. Who is your favourite philosopher?

There are too many to name but Rae Langton, who spent a lot of time in Australia, is a huge inspiration for me, and I like to think about how to precissify Robert Adams’ remark which seems to me to get to the heart of moral philosophy: “we ought, in general, to be treated better than we deserve”.

Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions, the impact these are having on our lives, our interactions, how we work and so on. What do you hope we learn or gain from this experience?

Truthfully I think the most we can hope for is a greater appreciation for the profound fragility of the things that normally keep us functioning. Our friendships, entertainment, ways of being in the world, all so easily threatened by simply not being able to leave the house very much. I have found that very humbling, and very difficult. I hope also we can learn to be a little more compassionate with ourselves about the fact that we are all creatures who need to live and will one day die. Before Covid, it was very easy to see each other and ourselves as our jobs, or athletic achievements, or how we’re measuring up to a set of criteria about how our lives “should” be going. Seeing everybody’s houses and children and needs via Zoom will I hope let us be compassionate about the fact that we all have them, and there’s no shame in taking care of them.

We’ve all had a guilty pleasure of sorts during the pandemic. Can you share with us yours?

I bought a robot vacuum cleaner and I like to follow him around and tell him he’s missed a spot.

Amazing. Let’s get to know you better. What is a standard day in your life?

I read a lot, work on [podcast] episode plans, put several thousand post-it notes on the wall – each one a piece of tape from an interview, a fact, a piece of theory, a well-phrased, or a scene – and rearrange them until I can see a story unfolding alongside a philosophical idea. I read philosophy, listen to a lot of radio and podcasts because there are so many clever people in that sphere whose work I admire, and try to stop by 9pm. Although if I’m honest, that’s rare these days.

You wrote a book – what is it about?

Stop Being Reasonable. It’s a series of true stories about how we change our minds in high-stakes moments and how rarely that measures up to our ideal of rationality. Each chapter features interviews I conducted with someone about a moment in their life that they changed their mind in a really drastic way: a man who left a cult, a woman who questioned her own memory of being abused, a man who changed his mind about his entire personality after appearing on reality TV, someone who learned their family wasn’t really their family, and so on. Each story highlights a sometimes-maligned strategy for reasoning that many of us turn out to use all the time, especially when it really matters: believing other people, trusting our gut, thinking emotionally, and so on. The book is a plea for a more capacious ideal of rationality, such that these things ‘count’ as rational thinking as well as the emotionless first-principles reasoning we usually associate with that term.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

People sometimes think ethical thinking promises a set of answers. It might, but I think it’s much more about learning to ask a different set of questions. So many of our disagreements and deepest divisions are built on argumentative frameworks that we almost never dredge to the surface and examine. We take things for granted about what matters, why, how to measure it, and what follows from the fact that those things matter. Learning to think ethically is about examining those things – about realising which systems of value we subscribe to by accident, and trying to make our value systems more deliberate.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to help your kid flex their ethical muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Testimonial Injustice

Ethics Explainer: Testimonial Injustice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Eleanor Gordon Smith 22 SEP 2020

Telling people things – or giving ‘testimony’ – is one of our quickest, oldest, and most natural ways of adding to human stores of knowledge.

Philosophers have spent thousands of years wondering when, and why, certain beliefs count as knowledge – and when certain beliefs count as justified. Many agree that when we are told something by someone reliable, trustworthy, and in possession of the facts, their testimony can be enough to justify a belief in what they say.

I can tell you that it will rain later, you can tell me which way the train station is, we can both go to a lecture by an expert and walk away knowing more.

But we can’t accept all the information we hear from other people. Not all testimony can ground knowledge – some of it is lies, errors or opinion. That’s why credibility is important to the process of learning by being told.

The enlightenment philosopher David Hume argued that we shouldn’t set our standing levels of credibility too high: he thought “testimonial beliefs” were only justified when we had back-up justification from other sources like our own eyes, readings, and observations.

Immanuel Kant, by contrast, thought that we had a “presumptive duty” to believe what our fellow humans told us, since believing them was a mark of respect.

Regardless of the debate about how much credibility we should give people, there’s no denying that how much credibility we do give plays a big role in what we can learn from each other, and whether we learn anything at all.

Sometimes we allocate credibility in ways that are unfair, unreasonable or outright harmful. Beginning in the 20th Century, Black and female philosophers started pointing out that women, people of colour, people who spoke with an accent, and people who bore visible markers of poverty were disbelieved at far higher rates than the general population.

Because of existing prejudices against these people, some ethicists posit, they are being systematically disbelieved when they speak about things they, in fact, are reliable experts about. This is what philosophers term “a credibility deficit”. People could experience a credibility deficit when they speak about elements of their own experience, like what it was like to be a woman in domestic servitude.

It could also include elements of the world around them – such as the denial of black people’s reports of violence by white men.

Credibility deficits are not just a matter of knowledge but a matter of justice: if we are not believed when we tell other people true things, we can be shut out of important social processes and ways of being recognized by other people. One of the most important ways that credibility deficits play out is in court, or in other reports to do with crimes and legal proceedings.

After abolition in the United States but before the civil rights movement, black peoples’ testimony was not recognised as a source of legal information in courts. That legacy has long undermined the way that black people’s testimony is viewed in courts, even today.

Philosopher Miranda Fricker uses a scene from To Kill A Mockingbird to highlight the way Tom’s race, when combined with his being in a white courtroom affects his Tom credibility. Though he is in fact telling the truth, and though there are no obvious reasons to disbelieve him, the white jurors in the American South are so trained by prejudice that they regard his race itself as a reason to disbelieve him. It is not the facts of the story itself that mean jurors do not believe it, but facts about who is telling it.

Clip: Tom Robinson’s cross-examination from To Kill A Mockingbird.

This was a common and tragic way that credibility deficits played out in the real world: there is a long history of white women being believed over black men even when they made false and damaging claims.

The tradition of “testimonial injustice” in philosophy argues that credibility misallocation is more than a mistake. It is an injustice because we have a moral duty to see other people as ‘full’ people and to treat them with respect, but discounting people’s word because of prejudice is a way of denying them that respect.

In some ways, to refuse to believe someone without defensible reasons is to refuse to recognise them as a person.

Philosophers like Miranda Fricker, Jose Medina, Dick Moran, and a long tradition of black feminist epistemology including Charles Mills and bell hooks have explored the ways that being a free and equal citizen requires being believed as one. There are wide-ranging debates among these thinkers over many areas inside testimonial injustice, including whether and why being believed is foundational to being seen as a person, what kinds of credibility we could ‘owe’ one another, and whether people besides the disbelieved party are wronged by a faulty allocation of credibility.

One important question is whether it could be wrong and if so to whom, to give out too much credibility instead of too little. If it’s unfair to afford someone too little credibility, what should we say of affording too much? Are they wrong? If so, why? And, who is wronged by giving someone more credibility than they deserve?

A case study that might demonstrate this question is the familiar setting of the classroom. A male teacher-in-training with six months experience might be regarded in the classroom as more authoritative than a female teacher with many years’ more experience. This need not mean that the students disbelieve the female teacher. They could simply believe the male teacher more readily, with fewer questions, and with more of a sense that he is credible and has gravitas in the learning environment.

They could simply give him more credibility than he deserves. Who is wronged by this, if the female teacher is still believed when she speaks? Are the students wronging themselves? Are they accidentally wronging the male teacher, even though he benefits from the arrangement? These are important open questions that ethicists are still debating.

Another question is what kind of credibility we have to give to others in order to do right by them. Hume knew that we could not believe everything we hear. How much must we believe, in order to avoid this distinctive form of injustice?

Despite these unresolved matters, testimonial injustice is an important ethical phenomenon to be aware of as we move through the world trying to be responsible speakers and hearers. It’s important to living ethically that we keep prejudice and it affects out of our beliefs as well as out of our acts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is every billionaire a policy failure?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

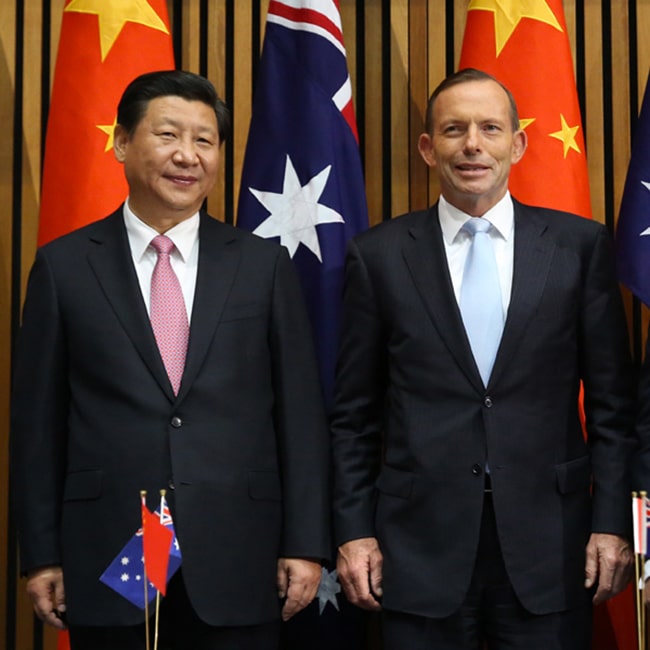

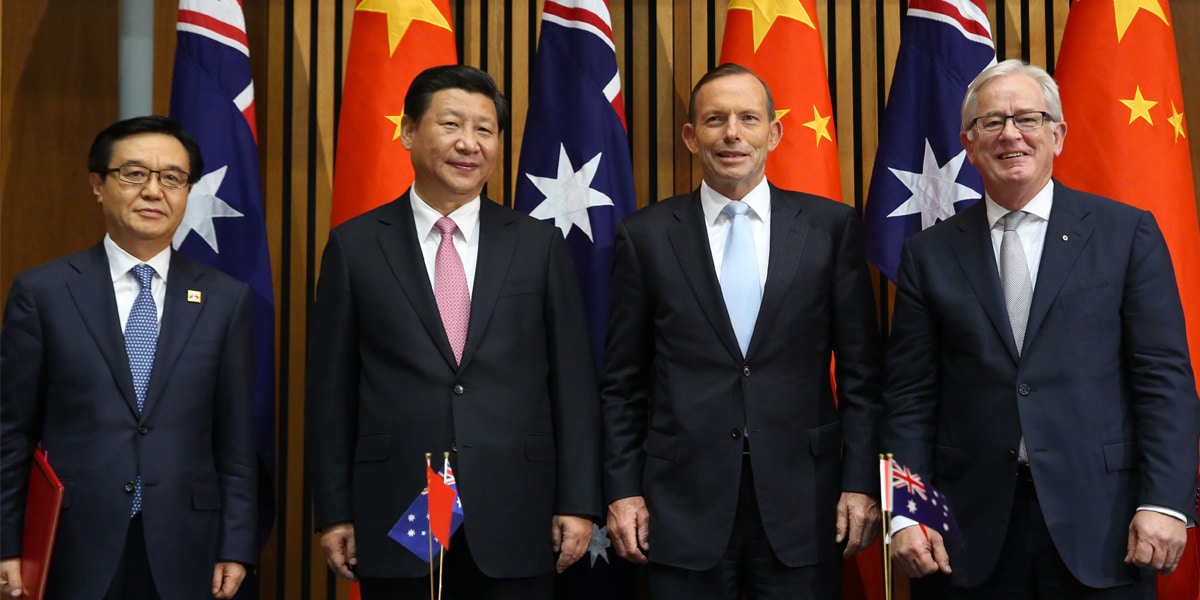

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard 17 SEP 2020

Former Aussie PM Tony Abbott’s recent appointment to an unpaid role as a trade adviser to the Johnson government in the UK has sparked controversy in both countries.

UK government MPs have continually been asked what it means to have a man who is, by the judgement of many in both countries, “a misogynist and a homophobe”, as well as a climate change denier and – more recently – sceptical about coronavirus lockdown measures.

In Australia, politicians, journalists and citizens have all questioned the appropriateness of a former Prime Minister accepting a position that leaves him serving a foreign government. Whilst Abbott has obligations under the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme that are designed to prevent conflicts of interest, there are many who believe Abbott is equipped with too much internal knowledge of Australia’s trade interests, internal party politics and regional issues in the Pacific – accrued as Prime Minister – for him to serve another government.

Given the range of questions that arise around both conflict and character, we made a list of some of the big ethical questions the Abbott situation brings up, and spoke to a few ethicists to help answer them.

1. Abbott is a private citizen now. Shouldn’t he be able to take any job he wants?

“Being Prime Minister isn’t like any other job,” says Hugh Breakey, a Senior Research Fellow at Griffith University’s Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law. “Abbott would have been privy to high level information and forward planning that he is obligated to hold secret.” If a potential employer of Abbott – whether in a paid role or not – would benefit from this situation, Breakey argues that it would give Abbott a conflict of interests.

But it’s not just a question of conflicts of interest. In situations like this, it is reasonable to consider whether this role was given as a “kind of payback for favourable treatment during his time in power,” Breakey says.

However, whilst Abbott’s appointment may generate potential conflicts of interest and are “legitimate lines of ethical inquiry”, Breakey believes they are not problems for Abbott’s appointment.

However, Simon Longstaff, executive director of The Ethics Centre, disagrees. “There just can be no guarantee that Britain’s interests will always coincide with Australia’s. Given this, the fact that one of our former Prime Ministers would ever serve a foreign power almost beggar’s belief,” he said.

2. If Abbott’s trade qualifications make him a good candidate, should we overlook his other beliefs and opinions?

“I believe that a representative of any country, in any honoured capacity like this one, should be a morally upstanding person. Tony Abbott is not that, given his history of misogyny, homophobia, and racism,” says Kate Manne, philosophy professor at Cornell University.

However, Hugh Breakey worries that an approach like this risks jeopardising our commitment to non-discrimination and supporting a diverse set of beliefs and ways of life. Sometimes, he says, ethics might require us to overlook the questionable beliefs of a potential political appointment.

“At least some of the views taken by Abbott on these matters have religious influences, and many similar (and, indeed, far more conservative) views are held by religious devotees across many of the world’s major faiths. Prohibiting from public offices and services all those who hold such views… would allow widespread religious discrimination.”

However, another complication arises when it comes to whose views and personality traits we tend to overlook. Cognitive biases, social norms and systemic beliefs like sexism and racism can mean we’re more likely to overlook controversial beliefs or difficult personalities when they belong to men, people who are straight or white.

Kate Manne suspects that “both women and non-binary people are far less likely to be viewed as truly qualified or competent, unless they’re also perceived as extraordinarily caring, kind, and what psychologists call ‘communal’.” She adds that the tendency to separate the professional and personal/political aspects of someone’s identity is “far less available to women and gender minorities.”

3. Should we label Abbott a misogynist or homophobe based only on his public comments and policies?

“The truth is, few people would know Tony Abbott well enough to say with any confidence what he truly feels or believes, and those who do know him paint a very different picture to the one sketched by his critics,” says Simon Longstaff. “A person can be opposed to same-sex marriage and yet not be a homophobe,” he adds.

However, for Kate Manne, the central question of misogyny or homophobia isn’t whether the person feels a certain way toward women or queer people, it’s what effect they have on those communities.

“Misogyny to me is not a personal failure or an individual belief system: it’s a system that polices and enforces a patriarchal order,” she says. “I define a misogynist in turn as someone who’s an ‘overachiever,’ or particularly active, in this system.”

Manne says, “misogyny on this view is less about what men like Abbott may or may not feel toward women, and more about what women face as a result of their toxic, obnoxious, and contemptuous behaviour.”

For Manne, this means Abbott can be reasonably called misogynist and homophobic on this basis. His status as a former PM and his very public comments have done considerable work to uphold a system that oppresses women and LGBTIQ+ people. She cites examples such as calling abortion the ‘easy way out’, standing next to a ‘ditch the witch’ sign or talking about feeling threatened by gay people as evidence of Abbott’s contributions.

4. How should we balance the need to reject some beliefs because they’re not morally acceptable or legitimate with our commitment to pluralism?

“Democracies gain critically in legitimacy by being able to conduct inclusive deliberations where diverse views can be raised and considered,” says Hugh Breakey.

“Naturally, no-one can or should expect immunity from social consequences for what they say in public discussion, Breakey adds. “The more that institutional sanctions are applied on the basis of positions taken in [controversial] debates the narrower the spectrum of positions that are likely to be defended, and the more that different views will fail to be represented.”

Kate Manne suggests a simple principle to test which voices we should accept as part of our political life: “It’s good to have a variety of voices, but those voices need not to silence or speak over the voices of other people,” she says.

“Abbott’s voice does not meet that simple test. “

Unlike Manne, Breakey doesn’t suggest Abbott’s views sit outside the realm of acceptable political opinions, he agrees with Manne’s principle. “If we want democracy to be more than the tyranny of the majority, or (worse still) rule by elites, then we need more civic tolerance afforded to those who think and speak in disagreeable ways.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Survivor bias: Is hardship the only way to show dedication?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Tim Walker on finding the right leader

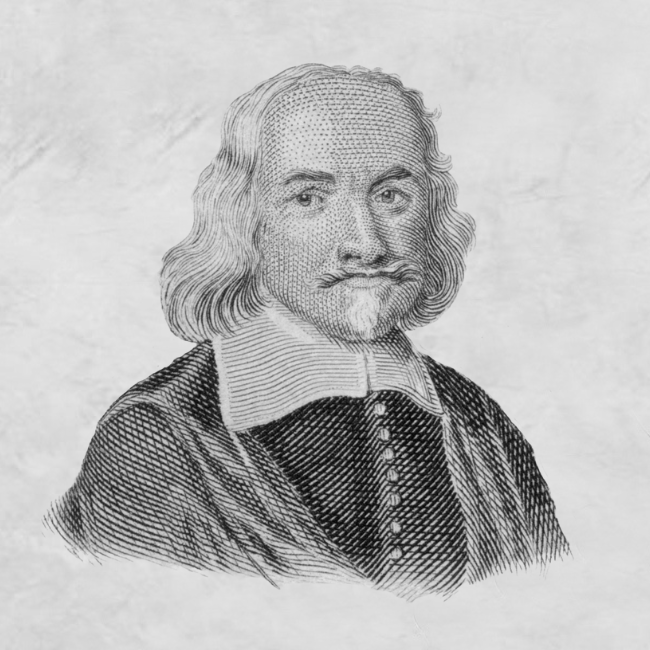

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 SEP 2020

What underlying driver created the great toilet paper gate panic of 2020?

At the onset of the pandemic, The Ethics Centre Fellow, Dr Matt Beard, University of Queensland philosopher and health researcher Bryan Mukandi, University of Queensland, and Australian philosopher and Princeton PhD candidate Eleanor Gordon-Smith joined in conversation. Together they discussed, dissected and explored a range of ethical issues rising during the early stages of the pandemic. In this extract, they discuss what COVID panic buying reflects about who we are, and what we value..

Matt Beard, TEC Fellow:

The kind of panic buying responsive that we saw from ordinary people at the beginning of this, what did that tell us about ourselves? For me that was a moment to really reckon and say what does it tell us that in the first sniff of a crisis, the first thing that we did was take care of us and ours. What does that say to us about the way in which we’ve set up this society?

Eleanor Gordon Smith, Philosopher:

The United States, the land that brought us Black Friday sales, did not hold back when it came to panic buying. What did it reveal about us? Less I think then it revealed about our circumstance.

Here’s what I think it revealed about us. We were afraid, and we didn’t feel secure, and we didn’t trust either us or the government around us to provide for us in the moment of crises where we would most need both those things.

More than anything particularly deep about our innate nature, which I know people argue about a lot, does this reveal that we’re fundamentally selfish? Well yes, but then people also drove themselves to food banks, and it revealed other things about kindness and solidarity, and all the nice things as well.

I think more than that it revealed something that we kind of already know, which is that the right configuration of circumstances can push ordinary people to behave in profoundly selfish and possibly evil ways.

We know that a lot of exercises of bad behaviour are perfectly ordinary, and what happens when people are frightened and insecure. More than what I think it told us about us, I think it told us something really disquieting about the faith that we had in our systems, which was that unless we did this unless we went out and kind of did this end of days, treading on each other’s necks for a can of beans we wouldn’t have enough.

I’ve been saying this for weeks, I don’t even like beans, I don’t know why I bought so many beans, everyone just transformed into people who really liked beans all of a sudden. But it told us that we were willing to do that.

In fact, we thought it is necessary that we do that because we were so unsure of the fact that other people, and or the government, and or the system would be able to provide for us if we didn’t do this kind of absurd others sacrificing thing. I think we were entirely wrong.

Byran Mukandi, Philosopher:

Here I disagree with Eleanor. Irene Watson, a legal scholar, in her book, “Raw Law”, she uses a Nunga word, Muldarbi for colonialism. There’s an image she paints of colonialism as this voracious monster, this voracious animal that just devours and consumes. And I just find that so incredibly apt.

I think it’s telling that for some groups in Australia, the relationship between ‘mainstream society’, and some communities is one that’s best classed as this voracious, consuming animal. This devouring thing.

As a sub-Saharan African, the quality of life I enjoy today as an Australian citizen, is inextricably linked to the poverty and deprivation, and the suffering that a lot continent sub-Saharan Africans, and a whole bunch of people around the world experience. Those two things are intimately intertwined.

There’s a lot of posturing in terms of our response to climate crisis around why China needs to do something first, but the fact is the Chinese industrial work, manufacturing work, goes into providing that which we, in the Western world, consume. There’s a sense in which we are ferocious, we devour.

The rush to buy toilet paper as though when the zombie apocalypse comes, the most needful thing is toilet paper… I mean, this isn’t a gastroenteric virus, it’s not like everybody’s going to be on the toilet, but little things, baking powder, toilet paper, tins of tomatoes and tomato paste, people were hoarding and panic buying non-essential goods.

I don’t think it was because the idea was this non-essential good is going to run out and I’m not going to make brownies or cupcakes, or whatever, and my life is going to come to an end.

I think we have a voracious appetite, I think we have a voracious consuming, devouring appetite. I think we have a particular relationship to the environment and to others, and I think this pandemic has just shone a light on who we are, as opposed to who we like to pretend we are and the image of ourselves we like to project.

This is an extract from a live-streamed event. Watch the full conversation from FODI Digital event, Ethics of the Pandemic, below. Don’t miss our next live-stream events at www.festivalofdangerousideas.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 9 SEP 2020

In the pandemic landscape, individual rights were challenged against a mutuality of care for our neighbours.

At the onset of the pandemic, The Ethics Centre Fellow, Dr Matt Beard, University of Queensland philosopher and health researcher Bryan Mukandi, University of Queensland, and Australian philosopher and Princeton PhD candidate Eleanor Gordon-Smith joined in conversation.

Together they discussed, dissected and explored a range of ethical issues rising during the early stages of the pandemic. This extract from the discussion considers Carol Gilligan’s theory around the ethics of care, and in particular her ideas around the mutuality of care and the idea that individual actions impact the whole.

Matt Beard, TEC Fellow:

One of the things that I keep coming back to, is this quote from the feminist philosopher, Carol Gilligan, who championed an approach, “the ethics of care”. She talks about this idea that we live on a trampoline, and whenever we move it kind of affects everybody else in the same way, it makes other people wobble, your activities cause discomfort to others.

And one of the things that this pandemic has crystallized for me is this sense that, this whole idea of this atomized individual with rights that cluster them off and divide us from other people, is kind of illusory. We are radically dependent on other people, we have this interdependence and these mutual obligations that inform our moral response.

And that got me thinking about how difficult it can be to muster that sense of mutual obligation. In a society that does just talk so heavily about ourselves as individuals, we’ve been conditioned to think about ourselves in almost exactly the opposite way to the way that this response requires us.

Have I set this up in the right way? Is it true we’ve been conditioned in this way? How do you think about this?

Bryan Mukandi, Philosopher:

It’s really complex, because on the one hand I think you’re absolutely right. I love that metaphor of the trampoline, and I completely agree, this idea of this autonomous free liberal individual, it just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. But at the same time, on the other hand, the fractiousness and fracturedness we’re witnessing in the US applies here too, in some really interesting ways, right.

So, yes, we’re all on this trampoline, but the real estate that you occupy on that trampoline makes the world of difference. And we have a kind of social structure, social organisation where there’s an investment in occupying good real estate [so] that when something happens – a natural disaster, a fire, floods, a pandemic – there’s an investment in being in a position of being able to enact something like that illusory autonomy.

I think about Martin Luther King’s idea of an inextricable “network of mutuality”. But he raises this in a sort of moment where African Americans are in a particular kind of relationship with white America. He acknowledges that there’s this mutuality, there’s this connection, but the nature of this connection is one that’s really detrimental to some groups of people as opposed to others.

And I also think about Frantz Fanon contribution to Hegel’s dialectic of recognition. This idea that our selfhood emerges in relationship with others, it’s like it falls apart in the colony because in the colony the white doesn’t want the colonized recognition, they want their labour.

So I think, while on the one hand, COVID has shown us that this ideal of autonomy – it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. It’s in really interesting ways though, I think it may, at least for some groups of people, legitimate this project of striving towards that kind of autonomy of occupying the best possible real estate on that trampoline, as opposed to reconfiguring the trampoline itself.

Eleanor Gordon Smith, Philosopher:

It’s a really good question.

And like Bryan, I think it’s a very complex one and one that we’re not going to compress either now or in a pandemic writ large. One thing I think that is kind of a shame for me living in the states and seeing the way the states is covered internationally is the way that a lot of the pressure to reopen is construed in these kinds of individual autonomous terms.

I have a lot of family and a lot of friends who I think are really genuinely very concerned about my proximity to New York at the moment. They feel like crisis, real proper, ‘everyone’s dead’ crisis, like blood –in–the–streets–type crisis, is right around the corner.

And my suspicion about why they feel like that is that they’ve seen these videos of women hanging out of cars at intersections blowing the horn at medical workers or protesters walking into government buildings, people with the American flag painted on their face, holding banners about the right to return to work.

These people are both, they’re a very individualistic face of this movement and the movement that they claim to be espousing is very individualistic. They’re making claims about people’s individual rights to get back to work and they are doing so claiming to speak as individuals.

But one of the things that I think it’s a shame that [coverage] obscures is that the pressure to reopen America comes from the fact that it’s a non-accidental feature of the US American system and the US economic system that it wants people to be back at work more than it wants them to be safe and well.

We encounter that from the mouths of individuals who present themselves as autonomous in saying things like ‘the cure cannot be worse than the disease’, but the pressure isn’t just from rhetoric or from individuals, it’s from the way the system is set up.

You look at the kinds of costs and debts that Americans incur just for functioning. Like if you get sick, that costs money and that creates debt, if you have a higher education system, even one that is continuing on Zoom at the moment, that costs money and that causes debt.

Both of these things coupled with just the usual systems of credit means that most Americans are in eye–watering amounts of debt, and then debt has interest which means that you’re incentivized to get back to work as fast as possible and you put people in a position where it’s not only rational but critical to get back to earning money because it costs money to earn less.

The way the system functions is such that not only do you create all these pressures, it’s then coupled with this narrative of individualism, telling people that both the source of the problem and the nearest solution is to be conceived of in these individualistic autonomous senses.

It’s a real shame when we reinforce and circulate these images of Americans protesting in the way that they are right now, because we obscure the fact that even these apparently maniacally individual faces are in fact the product of the same system that crushes the rest of us.

This is an extract from a live-streamed event. Watch the full conversation from FODI Digital event, Ethics of the Pandemic, below. Don’t miss our next live-stream events at www.festivalofdangerousideas.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Explainer: Hedonism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 25 AUG 2020

It can be argued that life isn’t something we have, it’s something we do.

It is a set of activities that we can fuse with meaning. There doesn’t seem much value to living if all we do with it is exist. More is demanded of us.

One of my favourite quotes about living comes from French Philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau.

“To live is not to breathe but to act. It is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence. The man who has lived the most is not he who has counted the most years but he who has most felt life. Men have been buried at one hundred who have died at their birth.”

Rousseau’s quote isn’t just sage; it’s inspiring. It makes us want to live better – more fully. It captures an idea that moral philosophers have been exploring for thousands of years: what it means to ‘live well’ – to have a life worth living.

Unfortunately, it also illustrates a bigger problem. Because we tend to interpret Rousseau’s guide to ‘Really Good Living’ in a particularly narrow way – that it’s all about vitality, seizing the day and YOLO.

This is a reality that professionals working in the aged care sector should know all too well. They work directly with people who don’t have full use of their organs, their faculties or their senses.

Months ago, before the pandemic, I presented Rousseau’s thoughts to a room full of aged care professionals. They felt the same inspiration and agreement that I felt.

That’s a problem.

If the good life looks like a robust, activity-filled life, what does that tell us about the possibility for the elderly to live well? And if we don’t believe that the elderly can live well, what does that mean for aged care?

The findings from the recent Aged Care Royal Commission reveal galling evidence of misconduct, negligence and at times outright abuse. The most vulnerable members of our communities, and our families, have been subject to mistreatment due in part to a commercial drive to increase the profitability of aged care facilities at the expense of person-centred care.

More recently, we have seen aged care at the centre of the Covid-19 pandemic. Over 250 deaths have been recorded in facilities across Australia from the virus and our State and Federal governments are fighting out responsibility.

Elderly residents have been prevented from being treated in hospitals, their facilities have been drastically understaffed and public commentators have wondered whether we ought simply to allow more of them to die.

Absent from the discussion thus far has been the question of ‘the good life’. That’s understandable given the range of much more immediate and serious concerns facing the aged care sector, but it is one that cannot be ignored, despite the urgent matters before us.

Whilst leaders and decision-makers must be held accountable, there is a deeper sense of shared responsibility we should all carry when it comes to our attitudes toward ageing and aged care.

In 2015, celebrity chef and aged care advocate Maggie Beer told The Ethics Centre that she wanted “to create a sense of outrage about [elderly people] who are merely existing”. Since then she has gone on to provide evidence to the Royal Commission because she believes that food is about so much more than nutrition. It’s about memory, community, pleasure and taking care and pride in your work.

Consider the evidence given around food standards in aged care. There have been suggestions that uneaten food is being collected and reused in the kitchens for the next meal; that there is a “race to the bottom” to cut costs of meals at the expense of quality, and that the retailers selling to aged care facilities wildly inflate their prices. The result? Bad food for premium prices.

We should be disturbed by this. This food doesn’t even permit people to exist, let alone flourish. It leaves them wasting away, undernourished. It’s abhorrent. But what should be the appropriate standard for food within aged care? How should we determine what’s acceptable? Do we need food that is merely nutritious and of an acceptable standard, or does it need to do more than that?

Answering that question requires us to confront an underlying question: Do we believe aged care is simply about providing people’s basic needs until they eventually die?

Or is it much more than that? Is it about ensuring that every remaining moment of life provides the “sentiment of existence” that Rousseau was concerned with?

When you look at the testimony provided to the Aged Care Royal Commission, a clear answer begins to emerge. Alongside terms like ‘rights’, ‘harms’ and ‘fairness’ –which capture the bare minimum of ethical treatment for other people – appear words such as ‘empathy’, ‘love’ and ‘connection’.

These words capture more than basic respect for persons, they capture a higher standard of how we should relate to other people. They’re compassionate words. People are expressing a demand not just for the elderly to be cared for but to be cared about.

Counsel assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Gray QC, recently told the commission that “a philosophical shift is required, placing the people receiving care at the centre of quality and safety regulation. This means a new system, empowering them and respecting their rights.”

It’s clear that a philosophical shift is necessary. However, I would argue that what’s not clear is if ‘person-centred care’ is enough. There is an ageist belief embedded within our society that all of the things that make life worth living are unavailable to the elderly.

As long as we accept that to be true, we’ll be satisfied providing a level of care that simply avoids harm, rather than one that provides for a rich, meaningful and satisfying life.

Unless we are able to confront the underlying social belief that at a certain age, all that remains for you in life is to die, we won’t be able to provide the kind of empowerment you felt reading Rousseau at the start of this article.

What it will do is provide a better version of what we already believe – that once you are at a certain age and stage of life, ‘living’ is no longer a real option? You must settle for existing.

At this stage, we can pump you full of our care, love, empathy and respect – and most people accept that we should do that – but you are no longer living for yourself. You are waiting, as humanely as possible, to die.

Unless we confront this deeper belief, any positive movement in aged care will struggle to provide residents with what we all hope for – a life worth living.

*This is an edited version of an article first published on 10th September 2019

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What's the use in trying?

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2020

In early 2020 I sat in a friend’s house on the coast of New South Wales listening to smoke alarms go off in canon, triggered by the air itself, thick with smoke from the active fronts of the worst bushfire season in living memory.

The roads were lined with scorched animals and the climate crisis seemed as inevitable as it did cataclysmic. It was unthinkable then that this moment of apparently superlative awfulness would, in a matter of months, recede to just one more entry in a year-long list of suffering, death, and massive-scale crisis.

The lucky of us stayed inside afraid for months. The unlucky died, or lost loved ones and could not go to their funerals. There was widespread and systematic police violence against black people and against the people who protested it. USD $3.6 trillion was wiped off the stock market in one week.

The first six months of 2020 presented an unusually literal illustration of an old ethical question: why bother when the conclusion feels foregone?

What many of us felt about the climate in January was a well-known phenomenon: the fatigue of feeling useless when we felt we could not rely on the powerful to make changes or on other people to do their part. This feeling was quickly matched by parallels in resistance to systemic racism, in fighting an economic downturn and even in pandemic compliance.

Early on in the COVID-19 outbreak, data modelling revealed that social distancing would only work if 8 out of 10 of us followed the rules. If only 70% of us stood six feet apart, washed our hands, and stayed inside for weeks on end, it would be as though none of us had. To the misanthropist who felt that 30% of people would surely disregard the rules, a motivational gap loomed: why do what I can to help, when I’m not confident it will.

Even to the most resiliently motivated, parts of 2020 posed this problem. Hundred-thousand strong protests in the United States were not enough to prevent the deaths of more unarmed black people, nor to prevent protestors themselves from being pepper-sprayed at close range.

The indefatigability of the protests seemed met by the indefatigability of the problem. For many people it became impossible to feel calm or ordered anywhere as long as case numbers rose. So it seemed foregone that our homes would not feel calm or ordered either, and the motivation to improve them frayed in proportion to the dishes in the sink.

The philosopher and psychologist William James knew that certain beliefs can be self-validating; that confidence in outcomes, however, we come by it, can make itself well placed. The sailors who think they can pull the heavy rope are more likely to summon the gusto and collective coordination required to make it the case that they can. This first half of 2020 was a vivid illustration of the photonegative; the fact that uncertainty about outcomes can be enough to puncture our drive to pursue them.

So what is there to be done? Few of us believe that this pessimism or uncertainty in fact means that it is not worth protesting, or washing our hands, or doing the dishes. We still rationally endorse that we ought to do these things. But it becomes a wrench, an act of shepherding ourselves, parent-like, and it wears us down. It leads us to misanthropy.

An answer lies in looking more closely at one facet of what 2020 has cost us. We lost the most unthinking parts of our lives; the well-worn routine of the drive home or the setup at the gym, the clockwork Wednesday night choir, the disappearance into a team practicing a physical skill.

These were moments where what we did was not to achieve, or to think, but to be in a process. It was immaterial to us whether we achieved victory or even improvement, since our commitment to doing them was not dependent on whether we did. What we wanted was to be absorbed, to be a creature who acts.

We are, unavoidably, creatures who act. But as philosopher Mark Schroeder has noted, there is an asymmetry between our options in thought and our options in action. We have three options about what to think: we can believe what is on offer, reject it, or withhold judgement. But in action we have only two options; act or do not. There is no way to be in the world that avoids this two-prong choice.

When we realize this, we can shift our focus in a way that avoids futility fatigue. Our moral duty to act – and so too, our motivation – need not be entirely derived from what will happen once we do. It may be that what we owe each other is action itself, and effort itself.

In turn, this can release us from some pressure that comes with knowing that our goals will be difficult to achieve and fragile once we get them. We can simply aim at the action itself. We can find in resistance, in participation, and in care, a goal which is not about the altering of the world but about the observation of the act itself.

In this state, our uncertainty is no longer a threat to our motivation. With this as our focus and our source of energy, we may find that we are, in the end, more effective at altering the world.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2020

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas traverses the cracks of our society across three flagship digital events this September and October.

We are living through a period of heightened fear and anxiety. The global pandemic has superheated three systemic problems that were already set to boil: government control of information, racism and climate change.

The three sessions will be streamed live on festivalofdangerousidea.com, with live interaction and questions from the audience. Ticket prices range from $10-$15 or $30 for all three conversations.

Our Festival Director, Danielle Harvey, has carefully curated these three speakers to for this dangerous time. In speaking about the programming, she said “the fallout from the pandemic is changing politics, economics and the every day so significantly.

FODI is a provocateur of big thinking, and it’s back to ask us: what should we be doing now to prepare for a post-pandemic landscape? And has COVID-19 offered opportunity or hindrance to tackling some of the biggest issues of our time in a new and profound way?”

Live stream sessions include:

-

Dangerous Fictions, Marcia Langton, 10 September 2020, 7PM

Langston is a fearless truth-teller who challenges the dangerous orthodoxies of a society that seems incapable of making peace with the truth of its own past.

-

Surveillance States, Edward Snowden, 24 September 2020, 7PM

Snowden asks us to consider the possibility that we may have more to fear from our own governments than from any external threat – and that our liberties have already been lost.

-

The Uninhabitable Earth, David Wallace-Wells, 11 October 2020, 11am

Wallace-Wells says there is no going back from the climate crisis and suggests the greatest challenge is navigating the future in a world that can’t agree how to face it together.

Challenging us all to stop and pay attention, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre and Co-Founder of FODI, Simon Longstaff, said these are pivotal issues are demanding creative solutions.

“The urgency of the moment might seem to demand every moment of our attention, the reality is that this is precisely the time when we need to look beyond the boundaries of the pandemic and come together and … think!”

These events follow on from the first FODI digital series in May which featured Norman Swan, David Sinclair, Claire Wardle, Kevin Rudd, Vicky Xu, Masha Gessen and Stan Grant. Past conversations are available on demand via www.festivalofdangerousidea.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Whose home, and who’s home?

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2020

Australian citizens who live overseas and want to return to Australia, with some exceptions, now have to pay for their mandatory two-week hotel quarantine.

This new rule applies for those returning to New South Wales or Queensland. It means that a single adult returning home must have AUD $3000 to pay for their stay. Last week New Zealand announced a similar policy: citizens returning home to stay less than 90 days will be charged for their quarantine.

Announcing the policy, NSW Premier Gladys Berijiklian said “Australian residents have been given plenty of time to return home, and we feel it is only fair that they cover some of the costs of their hotel accommodation”.

The locution of having “been given” time to return home sounded curious to many of us who reside overseas. We were unaware that living elsewhere had been a matter of taking.

In the comments sections of news articles about the announcement, the Premier’s sentiment was echoed by other Australians. A recurring theme appeared: overseas Australians who returned home now are being selfish to expect taxpayer help

What could fairness require, in a pandemic? It is not fair that some people will get COVID and others will not. It is not fair that some will die while others survive. These are circumstances where a question about fairness is simply not askable; there is only tragedy, which does not have a possible equitable distribution.

One way to be unfair in a pandemic might be to expose other people to risk. People arriving from overseas certainly do that, and it is crucial to Australia’s efforts to contain the coronavirus that it curbs the risk from international travellers. Like many other countries, Australia was within its rights to close its borders early to international travellers in recognition of this risk.

The very concept of citizenship, however, prohibits closing borders entirely. No matter where citizens ordinarily live, their government has a duty to allow them to cross the border of their home. This is what it means to be a citizen.

There is a problem of incommensurability here. How does the need to mitigate a biothreat weigh against the standing rights of citizens to cross a border? One is a value of rights and obligations; the other is a value of consequences and threat reduction. Neither of these values presents itself in a standardised unit to be compared against the other.

The question is not quite “how do we make a good decision?” but “which kind of good should we be interested in?”. This is a fairly common problem.

Not all of the things we want governments to provide can be coherently measured against each other, so when they come into conflict, it’s not clear how to even begin making the trade. Privacy against safety, health against freedom, service provision against non-interference.

The Government appears to have chosen fairness as the value to adjudicate between the two. The Premier described the policy as “only fair”, since “Aussies overseas have had three or four months to figure out what they want to do”. Prime Minister Scott Morrison echoed this, saying overseas Australians “obviously delayed [their] decision”, and Winston Peters of the New Zealand First Party said that asking taxpayers to pay for fellow citizens’ quarantine was “grossly unfair”.

There are two features of the decision that challenge the terms of fairness here. One is that it seems only to apply to Australians overseas. We would not, for instance, describe it as “only fair” to deny Medicare coverage to an Australian at home who contracted COVID-19 after breaking quarantine rules, even though there is an argument that this is ‘only fair’. Like the quarantine fee, it would mean that those who had ‘plenty of time’ to follow the rules did not impose a burden on the taxpayer when an emergency befell them.

The second is that it is not clear that fairness is the value we should default to in the midst of a global pandemic. In an article for Guardian New Zealand, Elle Hunt suggested that these policies are a failure of empathy. “Discriminating against all but the most wealthy members of the diaspora is a rare failure of not just compassion but imagination – to reach a more equal solution, and to imagine the painful personal circumstances in which it might be warranted.”

Empathy asks different things of a government than fairness. It asks for mercy and the maximum provision of services to those who are suffering. It asks for an imaginative capaciousness about what life is like for citizens whose jobs, families, friends and visas would have been in peril if they had returned earlier. It asks for magnanimity, forgiveness, and generosity.

Empathy may not be a viable long term guiding principle for a political party. But in a pandemic, we may find that the alternative language of fairness and moralising either loses its footing entirely or forces us to absurd conclusions.

“Only fair” was how the Premier described the policy, but we have more values than only fairness. A global emergency may be the time to use some.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships