It’s time to talk about life and debt

It’s time to talk about life and debt

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 17 JUN 2022

It’s no secret that things are getting more expensive.

Over the last few months Google searches for “the cost of living” have increased by 10 fold, and it’s no surprise. The price of vegetables has increased by almost 30%, some used cars are up over 45%, petrol is at the highest rate in history, and a string of interest rate rises have hit for the first time in more than a decade. Millions of Australians are feeling the financial stress of keeping a roof over their head, keeping the lights on and putting food on the table. So what’s going on?

The answer is… it’s complicated. We have found ourselves in the perfect storm of frequent extreme weather events, the effects of climate change on crop production, pandemic-affected supply chains, and a war in Ukraine. And as a result of all of these factors which are very much out of our control, we are experiencing rocketing inflation and a cup of coffee will now set you back over $5. So how can young people, whose wages have been stagnating for years weather this storm and better understand their finances?

Let’s talk about debt

For as long as we have ascribed value to little disks of metal, we’ve been conditioned to believe that accumulating debt is a bad thing, and that we should aspire to have money squirrelled away for a rainy day. After all, the majority of us are paying off some form of debt whether it be a mortgage, a business loan, or a student debt – so owing money certainly shouldn’t be taboo.

Which is why our latest podcast, Life and Debt says it’s time we stopped demonising debt and started thinking of it as a part of life.

Created by the Young Ambassadors from our Banking and Finance Oath (The BFO) initiative, this four– part podcast series takes a deep dive into debt, what role it has in our lives and how we can make better decisions about it. According to Young Ambassador, Cameron Howlett we need to rethink our relationships with being in the red. “We wanted to encourage people to think, discuss and engage with the topic because if you’re uncomfortable with debt, you’ll never really have a healthy relationship with it.”

Howlett hopes the podcast will encourage a more nuanced discussion about debt, “we all have some good experiences and bad, but what we have found consistently was that we were all a bit nervous about debt.” The series, which features financial advisors, journalists, finfluencers, psychologists and historians hopes to debunk the shame and stigma around debt especially for younger listeners. Cameron continues, “we want to get people from that step of being too terrified of debt or credit to be able to think whether or not it’s right for them”, so how can we be a little more discerning when it comes to different types of debt?

“If you’re uncomfortable with debt, you’ll never really have a healthy relationship with it.”

The good the bad and the ugly debt

During the pandemic, we all did our share of online shopping. Buy now, pay later services made it easy for us to get that instant gratification hit that comes with receiving parcels in the mail, without the ensuing depression that results from looking at one’s negative bank balance. These services posted huge profits during the pandemic, and because they’re so easy to set up and use, people are now using apps like AfterPay and ZipPay to purchase everything from a new outfit for the weekend, to groceries, and childcare. Unlike credit cards and banks, Buy now, pay later companies don’t ask any questions about whether their customers can actually afford to make the repayments, and as a result a lot of young people are racking up thousands of dollars in debt using these financial services.

So what exactly is good debt and bad debt, and how can we differentiate between the two?

According to Iqra Bhatia, a Young Ambassador from the Banking and Finance Oath initiative, “attitudes towards debt are changing, young people need to educate themselves more on debt and be aware of the resources available”. Instead we need to shift our thinking, “Afterpay is not that different from credit cards – it’s essentially the credit card of our generation.”

“Attitudes towards debt are changing, young people need to educate themselves more on debt and be aware of the resources available.”

It’s not all doom and gloom

It’s clear we need to start understanding money from a younger age. While lessons in financial management traditionally consisted of a few pointers offered by parents at the dinner table, we are now starting to see financial literacy programs introduced in the high school curriculum. But more work needs to be done.

Debt is something that, at different points throughout all our lives we will all encounter and take on, whether it be small, like agreeing to buy the next round at the pub, or a little more daunting like taking on a HECS debt at university or taking out a mortgage to buy an apartment.

Debt can be emotional, it can feel like you’re signing away a little piece of your freedom, but it can also be empowering and necessary. And debt is changing, we’re grappling with the buy now, pay later industry now, and what form debt will take over the next few years. Which is why it’s important to stay educated and in touch with our values so we can make decisions for our bank balances and our futures.

Life and Debt is available to listen to on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

This podcast is a project from the Young Ambassadors in The Ethics Centre’s Banking and Finance Oath initiative. Our work is made possible by donations including the generous support of Ecstra Foundation – helping to build the financial wellbeing of Australians.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why Australian billionaires must think “less about the size of their yard” and more about philanthropy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 JUN 2022

From The Matrix to Euphoria, writer, philosopher and poet Joseph Earp has profiled some of the greatest philosophers, TV shows, films, music and pop culture moments to date, discussing what they can tell us about ourselves and the world.

Which is why we’re excited to share we’ve recently appointed Joseph as an Ethics Centre Fellow. Currently undertaking his PhD at The University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume, we sat down with Joseph for a brief get-to-know-you chat to discuss ethics, his favourite philosophers, and the role of pop culture in society.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

You learn the language of institutional philosophy by reading it, and – as long as your financial and geographical circumstances allow for it – by studying it in an academic setting. But the central questions that drive philosophical work are innate to almost all people, regardless of academic study.

I am a pragmatist, so I don’t believe that philosophers hold insight that stretches beyond the understanding of those who haven’t studied the discipline. As philosophers, we are merely using a certain vocabulary to ask our questions. I grew to love that vocabulary in my late twenties through university study, under the guidance of my honours and PhD supervisor, Anik Waldow and those academics I studied closely with throughout my undergraduate degree. Most notably, these academics include Caroline West, who I believe to be one of our country’s most unique, inspired, and challenging thinkers – even and especially as I disagree with her – and David Macarthur. My study with these people is what drew me to being a philosopher in the strictest sense. But I think we philosophers are, thankfully, just doing what everyone else is doing.

Do you specialise in any key areas?

Generally, I write about popular culture, emotion, and virtue ethics, but my key area of specialisation is the philosophy of sex. I think that we sadly retain, in many cultures, a suspicion and fear of sex – one that infringes on our ability to self-describe and live our most flourishing lives.

I often think of a story about Pablo Picasso. Towards the end of his life, he was so rich and famous that he could draw any object in the world, whether it be a Ferrari or a mansion, and his drawing would be worth more than the object itself. He could sell a sketch of an object, and use the accrued capital to buy that object – which is a way of saying he could create changes by charting what he felt had already changed. It seems to me that’s the potential, and the potential harm, of philosophical thinking. We construct the world by calling it what we think it is, and for a long time, our views on sexuality have created a world that contains a lot of fear and sexual repression, both internally and externally maintained.

Your honours thesis focuses on emotional contagion. What place does emotion have when it comes to ethics?

Personally, I think it’s emotion all the way down when it comes to ethics, as with most things. David Hume is the philosopher that much of my work has operated in the framework of, and I agree with Hume that when we talk about “rationality” – a word that is sometimes conceived as being opposed to emotion – we are really just talking about a certain kind of emotional work.

What have you been working on this year?

One of the most profound experiences of both my intellectual and personal life has been connecting with a community of thinkers whom I met largely through my university work – all of them world-class philosophers, some of them write for, and work with, the Ethics Centre; and some of them no longer consider themselves strictly philosophers at all. In particular, Georgia Fagan, Danielle Turnbull, Finola Laughren, Eleanor Gordon-Smith, Grace Sharkey, Oscar Sannen, Mitch Flitcroft, Alexi Barnstone, Elle Lewis, Mitchell Stirzaker, Henry Barlow, Zach Wilkinson, Finn Bryson, and Henry Hulme.

All of these people have work that you can, and should, find online through an easy Google search, and work which I believe in every case benefits the world, and drives real change. What else is philosophy for? I am continually astonished by the intellect and bravery of these collaborators and friends. I consider myself useless without them. When I think about the real work that I have done this year, it is not anything I have written, but conversations with these people, and the ways I have learnt from them.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or writer?

Hume is the philosopher whose writing I know best, but I believe the thinker you apply the greatest amount of study to is usually the one who you have the strangest, most frequently frustrated relationship with. So my favourite – as in, the philosopher who serves as the background to almost all of what I think and do, and who I have the most uncomplicated connection to – is the pragmatist Richard Rorty. It’s Rorty who cuts through the chaff by asking, again and again, one of the simplest questions: what is the real-world application of our work? And it’s Rorty who tells us that we should remember we can make ourselves whoever we want to be.

Your writing covers a lot of tv series, films and music. Why is pop culture important?

Again – it’s Rorty. Rorty believed that social change isn’t led by philosophers, particularly those analytic philosophers who consider their work to be sorting through “falsehoods” and “truths”. For Rorty, philosophers inspire prophets and poets, and prophets and poets are the ones who do the work of change. That is, for me, the importance of pop culture. That form of art is guided by philosophical questions, and led by prophets and poets, and represents a way of understanding a culture and a vocabulary. It’s how lives are changed, and possibilities for self-description are opened up

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

The poetry collection The Cipher, by Molly Brodak, a writer who means a great deal to me; the pornographic film Corruption by perennial sadsack and visionary Roger Watkins, which I try to return to every month or so; and the song ‘Lark’ by Angel Olsen, often enough that I should probably take a break.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

We all play the game of ethics, and we all want to play it better, and we’ll never play it well. That, in fact, is the joy – the trying, and the starting again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Trust

Trust forms the foundation for relationships, cooperation, social interaction and the development of societies, but it is equally important as it is dangerous.

From hunter-gatherers to globalised societies, trust is the essential lubricant of social functioning at any scale.

Imagine something as simple as driving to get groceries. You leave your house, get in your car and drive to the shops. In doing so, you’re relying on several overlapping layers of trust that are engrained in our society. You trust that:

- your neighbours won’t break into your house while you’re gone

- the police will deal with them appropriately if they do

- the insurance company will deal with you fairly if they do

- the manufacturer of your car was responsible and competent

- the other drivers on the road will all obey the traffic laws

- your money has retained its value and that the shopkeeper will take it

and so on. Almost every aspect of our lives depends on these underlying relationships of trust with the people around us, and when they are betrayed – especially repeatedly – they can crumble and leave behind instability.

When we trust others, we’re depending on them to fulfil expectations that aren’t guaranteed to be met and that leaves us vulnerable or at risk.

Vulnerability is an important aspect of trust; it creates a tricky tension between our need to rely on others and our need to protect ourselves from risk and harm. To avoid vulnerability and guard against betrayal, we might decide not to trust anyone, but that leads to a miserable life: a life devoid of friendship or intimacy, and ultimately of convenience too, as we need to trust strangers on an almost daily basis, from taxi drivers to teachers to police.

So, we must trust others and learn how and when to be vulnerable to live a fulfilling life.

We trust people by giving them the space and freedom to do what they have been trusted to do, without necessary observation or oversight, with the expectation that they’re:

- Competent enough to do what they have been trusted to do and

- Willing to do it.

“Trust is an ability to rely on somebody to do what they have said they will do, even when no one is watching them” – Simon Longstaff AO

Trust and trustworthiness

An important distinction is the difference between trust and trustworthiness. Trust is an attitude that we have towards others (or sometimes ourselves!) that indicates our hope or expectation that the object of our trust is trustworthy.

Trustworthiness is a property or characteristic of others and in ideal situations has a reciprocal relationship with trust. That is, ideally, trust is an attitude towards trustworthy people, and trustworthy people will be trusted.

Of course, we have all experienced that we don’t live in an ideal world. Often untrustworthy people are perceived to be trustworthy because of lies, clever marketing or overwhelming charisma. Equally, trustworthy people can often be misrepresented to appear untrustworthy.

Interpersonal trust and institutional trust

There are two kinds of trust, the most common and intuitive kind being interpersonal trust – that is, trust between individuals. We might trust our friends with secrets or trust our family with babysitting or trust other drivers with our lives on the road.

A trickier kind of trust is that of institutions and government. They’re not as directly accessible as individual people

Nevertheless, we can and do trust institutions and governments to do as they say they will do, or what they are supposed to do: act in the interests of their people. This is a hallmark of society. But when this trust is eroded, we are left with an eroded society.

The ethics of trust

One of the first practical problems is knowing whom to trust. It’s easy to rely on perceived authority figures in our lives, and often we will simply need to trust that the people who are close to us are looking out for us, but in general we should be on the lookout for consistent moral behaviour.

Ultimately, there is no way to know whom to trust with certainty, but there are many indicators we can use to decide. Are they an honest person? Have they been reliable in the past? Are they self-centred or do they concern themselves with the wellbeing of others? Answering questions like these can help to minimise the risk you take on if you choose to trust someone.

- How do we rebuild trust?

- How should we act if we don’t trust someone?

- If someone breaks our trust, should we distrust them?

- When or how often should we re-examine our trust of someone?

- When is trust a good thing? When is it bad?

- What’s so important about vulnerability?

Answering these questions involves a complex mix of knowing how trust works, knowing the habits, motives and values of others, and knowing ourselves.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Sally Haslanger (1955-present) is one of the most influential feminist philosophers in contemporary philosophy. She is one of the pioneers of social philosophy and works to make the field of philosophy more inclusive.

She has some interesting life experiences, to say the least. Haslanger was born in 1955 in Connecticut, but moved to Los Angeles in 1963, where Jim Crow laws legalising racial segregation were still in effect. Moving from an unsegregated to a segregated part of the US as a child had an impact on her philosophical interests.

Her mother and grandmother were Christian Scientists, a small sect of Christianity that doesn’t believe in modern medicine, and she grew up attending their church. Later, her family moved to Texas where she attended an Episcopal boarding school, and started college before she had finished high school.

In a Q&A with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ( MIT), Haslanger says that her interest in feminist philosophy was catalysed when she was sexually assaulted as an undergraduate student at Reed University. Afterwards, she became involved in feminist activism, especially during her time as a graduate student at University of California, Berkeley. Later in life, she and her husband adopted and raised two African-American children. Haslanger says that these life experiences have played an important role in directing her philosophical interests.

What is race? What is gender?

While these seem like straightforward questions, Haslanger has spent a large part of her academic career trying to answer them. Race and gender are categories that allow us to group people in particular ways, predominantly based on physical characteristics. However, she doesn’t believe that the categories of race and gender refer to just physical characteristics, they also refer to social positions. Social positions refer to where someone fits into their society: – they could be in a privileged position or a more marginalised one.

“On my view,” she said, “both race and gender are social positions that individuals occupy by virtue of their body being interpreted a certain way.”

In 2000, Haslanger published what is now one of her most well-known and controversial papers: Gender and Race: (What) are they? (What) do we want them to be? In her paper, one of the things she tried to do is find a characteristic that all women have or experience. The characteristic she finds and defends in her paper is systematic subordination. On Haslanger’s view, to be a woman is to occupy a lower position in society because of the way that her body is interpreted by others.

Her definition sparked controversy amongst transgender rights activists. Some people identify as women, but are not necessarily perceived by society as women. Haslanger’s definition of a woman excludes these people, – namely, trans women who have not yet transitioned.

Since the paper was published, Haslanger has taken on a lot of the criticism and worked to make her definition more inclusive. However, she still holds that gender and race refer to more than physical characteristics; they also refer to positions within society.

Advocacy and inclusivity

Haslanger feels strongly about promoting feminist causes outside of the field of philosophy. During the 2016 US presidential election, she wrote about some of the ways Hillary Clinton’s campaign was being undermined by sexism.

“As long as ‘being presidential’ and ‘looking presidential’ are about being and looking masculine, we will be unable to address what is ripping [the US] apart as a country.”

Within the field of philosophy, she is a strong advocate for inclusivity and making the field a more inviting space for women and people of colour. Now, as a philosophy professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Haslanger predominantly teaches courses in social and political philosophy, feminist philosophy, philosophy of race, and history of philosophy.

To boost participation from traditionally underrepresented groups in philosophy, Haslanger worked to create a summer program alongside a few other philosophers in 2014. Philosophy in an Inclusive Key Summer Institute (PIKSI) creates a space for underrepresented undergraduate students to work in more formal areas of philosophy (such as logic and metaphysics) or in areas that may be seen as less important and rigorous (such as the philosophy of gender and race).

Haslanger is also the founder of the Women in Philosophy Task Force (WPHTF), which is a group of women who work to coordinate initiatives and intensify the efforts to advance women in philosophy.

“Philosophers spend a lot of time worrying about the mind: what is it? How does the mind relate to the body? They can hardly get a handle on the mind, so the social is completely out of reach. I’m a little impatient. I’m not going to wait until the mind is figured out to figure out the social world.” – MIT Q&A

Sally Haslanger has had a considerable impact on inclusivity in philosophy. Her work has encouraged philosophers and activists to investigate and question what we thought we could take to be truths about race and gender. Her work today continues to facilitate important discussions on how society functions and what we might be able to do to make it more equitable.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Tyson Yunkaporta is a researcher, arts critic, poet, and traditional wood carver. He works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges and is the founder of the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab at Deakin University.

A scholar of free-ranging ideas

Yunkaporta is not your typical academic. In a recent interview, he said:

“I try to avoid naming anything. And I try to avoid making too much sense, and I try to say things a bit differently every time and to mix it up. And I’ll make points that you can’t put together. I do that quite deliberately because I don’t want the things I’m thinking or working on to become an ideology or a brand, or something that people can use as a name… you’ve got to avoid that packaging and repackaging of ideas and let these things be free-range.”

Yunkaporta tries to keep his writing and discussions “free-range” because he doesn’t want to give complex ideas or concepts an “artificial simplicity.”

According to Yunkaporta, when we simplify complex ideas, they can become easily distorted or manipulated and the original intention behind them can become lost. But more problematically, when we simplify complex ideas, we fail to see how they connect to the larger patterns of creation at work.

“There is a pattern to the universe and everything in it.”

Nothing is really created or destroyed, it merely moves and changes. When we start to pay attention to the way that things move and change, and take note of the patterns that they make, we gain a better understanding of the world around us.

This is important, Yunkaporta states, because “future survival of all life on this planet will be dependent on humans being able to perceive and be the custodians of the patterns of creation again.”

Indigenous thinking can save the world

Yunkaporta’s recent book Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, is all about identifying and learning from the patterns of creation.

Sand Talk has sometimes been described as an exercise in “reverse-anthropology”, because rather than looking at Indigenous knowledge systems and practices from a Western perspective, Yunkaporta examines Western knowledge systems and practices from an Indigenous perspective.

He is careful about what knowledge he shares in the process, explaining that symbolic knowledge is often restricted (for example, by age or birth order) or is only appropriate for a specific places or groups (for example, members of particular clans).

However, he shares enough to help his readers start to recognise patterns in the world around them and to “come into Aboriginal ways of thinking and knowing, as a framework for the understandings needed in the co-creation of sustainable systems.”

Although Yunkaporta believes that sustainable systems cannot be manufactured by individuals (this is something that we must undertake collectively), he does think that each of us plays an important role as an agent of sustainability.

Agents of sustainability have four main protocols or guidelines, according to Yunkaporta: diversify, connect, interact, and adapt.

These guidelines tell us that we should diversify our interactions, so that we engage with people and systems that are dissimilar to ourselves and what we’re used to.

We should also aim to expand the networks of people that we currently engage with, so that we connect with as many new people and engage with as many new systems as we can.

Through these connections, we should also share knowledge, energy, and resources. But most importantly, we should allow ourselves to be transformed by the knowledge, energy and resources that are shared with us.

Ironically, Yunkaporta believes that frameworks are nothing more than “window dressing.” Yet, as he himself highlights, the four main protocols for sustainability agents are a kind of framework for sustainability.

This contradiction is, however, just part of Yunkaporta’s style. He describes his work as a “free-range ramble that should never be taken at face value.”

He writes to provoke thought and reflection in his audience, not to give them all the answers. After all, he muses, “perhaps the worst possible outcome of this work would be civilisation embracing these ideas.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

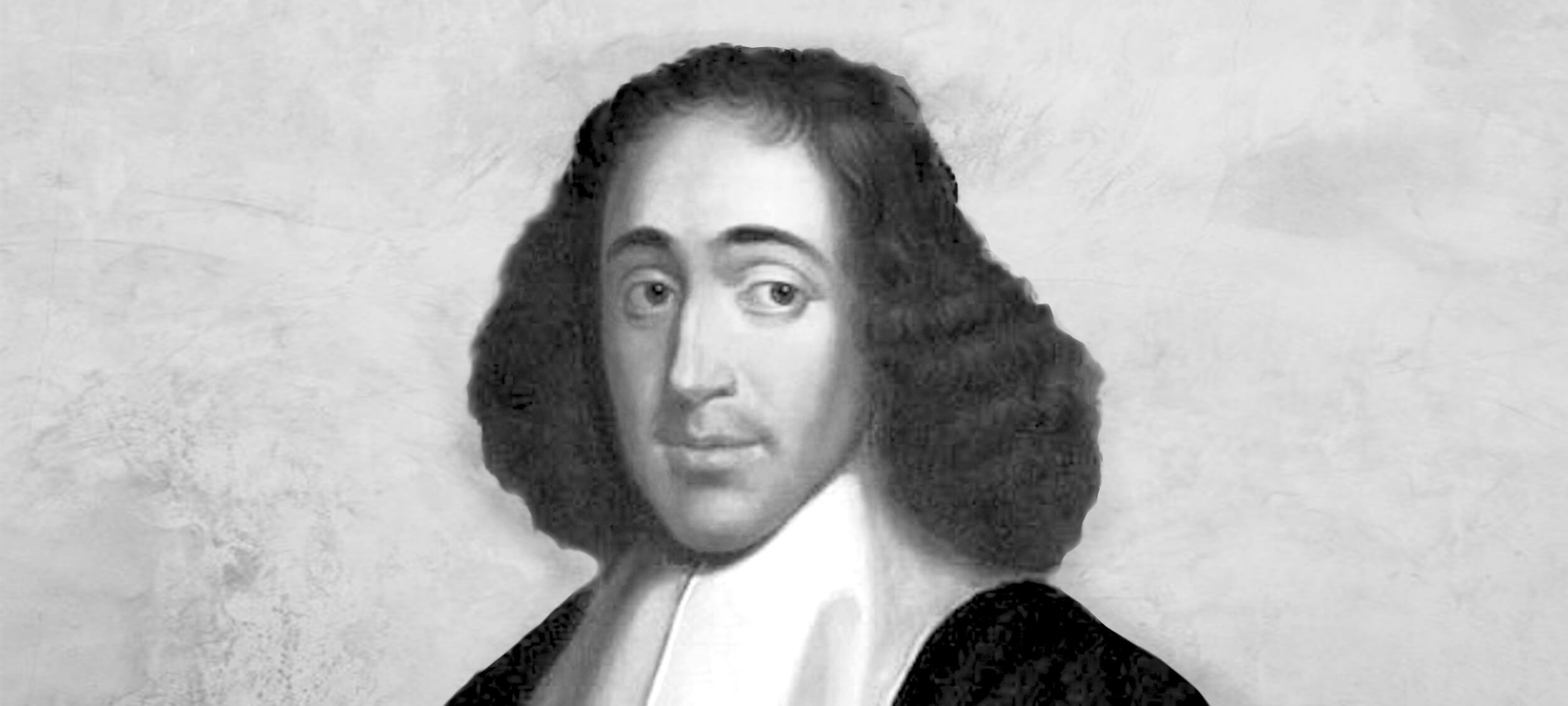

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Often, when we try to understand something, we ask questions like “What is it for?”. Knowing something’s purpose or end-goal is commonly seen as integral to comprehending or constructing it. This is the practice or viewpoint of teleology.

Teleology comes from two Greek words: telos, meaning “end, purpose or goal”, and logos, meaning “explanation or reason”.

From this, we get teleology: an explanation of something that refers to its end, purpose or goal.

For example, take a kitchen knife. We might ask why a knife takes the form and features that it does. If we referred to the past – to the process of its making, for example – that would be a causal (etiological) explanation. But a teleological explanation would be something that refers to its end, like: “Its purpose is to cut”. Someone might then ask: “But what makes a good knife?”, and the answer would be: “A good knife is a knife that cuts well.” It’s this guiding principle – knowing and focusing on the purpose – that allows knife-makers to make confident decisions in the smithing process and know that their knife is good, even if it’s never used.

What once was an acorn…

In Western philosophy, teleology originated in the writings and ideas of Plato and then Aristotle. For the Ancient Greeks, telos was a bit more grounded in the inherent nature of things compared to the man-made example of a knife.

For example, a seed’s telos is to grow into an adult plant. An acorn’s telos is to grow into an oak tree. A chair’s telos is to be sat on. For Aristotle, a telos didn’t necessarily need to involve any deliberation, intention or intelligence.

However, this is where teleological explanations have caused issue.

Teleological explanations are sometimes used in evolutionary biology as a kind of shorthand, much to the dismay of many scientists. This is because the teleological phrasing of biological traits can falsely present the facts as supporting some kind of intelligent design.

For example, take the long neck of giraffes. A shorthand teleological explanation of this trait might be that “evolution gave giraffes long necks for the purpose of reaching less competitive food sources”. However, this explanation wrongly implies some kind of forward-looking purpose for evolved traits, or that there is some kind of intention baked into evolution.

Instead, evolutionary biology suggests that giraffes with short necks were less likely to survive, leaving the longer-necked giraffes to breed and pass on their long-neck genes, eventually increasing the average length of their necks.

Notice how the accurate explanation doesn’t refer to any purpose or goal. This kind of description is needed when talking about things like nature or people (at least, if you don’t believe in gods), though teleological explanations can still be useful elsewhere.

Ethics and decision-making

Teleology is more helpful and impactful in ethics, or decision-making in general.

Aristotle was a big proponent of human teleology, seen in the concept of eudaimonia (flourishing). He believed that human flourishing was the goal or purpose of each person, and that we could all strive towards this “life well-lived” by living in moderation, according to various virtues.

Teleology is also often compared or confused with consequentialism, but they are not the same. If you were to take a business that specialises in home security, for example, a consequentialist would tell you to look at the consequences of your service to see if it is effective and good. Sometimes, though, it will be hard to tell if the outcome (e.g., fewer break-ins or attempted break-ins) can be attributed to your business and not other factors, like changes in laws, policing, homelessness, etc., or you might not yet have any outcomes to analyse.

Instead, teleological approaches to business decision-making would have you focus on the purpose of your service i.e., to prevent home intrusion and ensure security. With that in mind, you could construct your services to meet these goals in a variety of ways, keeping this purpose in mind when making hiring decisions, planning redundancies, etc., and be confident that your service would fulfil its purpose well (even if it is never needed!).

But how do we decide what a good purpose is?

Simply using a teleological lens doesn’t make us ethical. If we’re trying to be ethical, we want to make sure that our purpose itself is good. One option to do this is to find a purpose that is intrinsically good – things like justice, security, health and happiness, rather than things that are a means to an end, like profit or personal gain.

This viewpoint needn’t only apply to business. In trying to be better, more ethical people, we can employ these same teleological views and principles to inform our own decisions and actions. Rather than thinking about the consequences of our actions, we can instead think about what purpose we’re trying to achieve, and then form our decisions based on whether they align with that purpose.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 MAR 2022

Slavoj Žižek (1949-present) is a contemporary leftist intellectual involved in academia as well as popular culture. He is known for his academic publishing in continental philosophy, psychoanalysis, critique of politics and arts, and Marxism.

Žižek is remarkable for combining an esoteric life of abstract academic enjoyment with political activism and engagement with current affairs and culture. His political life goes back to the 1980s when he campaigned for the democratisation of his home country, Slovenia (then part of Yugoslavia), and ran for the Slovenian presidency on the Liberal Democratic Party ticket in 1990. He has since become known as one of the world’s leading communist intellectuals, although he is far from dogmatic. Žižek has aroused controversy with his revisionary takes on Marxism, criticisms of political correctness and strategic support of Donald Trump in 2016.

Žižek is known as a provocateur, trigger-happy with an arsenal of dirty jokes, ethically challenging anecdotes, extreme statements, and stark inversions of glib platitudes. But his ‘intellectualism’ and provocations are neither nihilistic nor unprincipled.

Žižek’s oldest loves are cinema, opera and theory. He is sincerely committed to art and ideas, seeing them as both tools for sharpening up political struggle as well as part of what that struggle is ultimately all about. As he once put it: “we exist so that we can read Hegel.” That is, while philosophy may be useful, it’s also an end in itself, and needs no practical application to justify its existence or enjoyment.

As for his provocations, they are either the expression of a genuine, open-minded inquiry, or an effort to liberate us from the gravitational force of what he calls ‘ideology,’ a central target of his work.

Indeed, the revival of the Marxist notion and critique of ideology is one of Žižek’s most profound contributions to the contemporary conversation in this space and is a key part of his innovative synthesis of Lacanian and Marxist theory.

For Žižek, ideology is not primarily about our conscious political beliefs.

Instead, ideology is something that shapes our everyday behaviour, norms, habits of thought, architecture and art. It can be found everywhere from Starbucks coffee and toilet seat designs to Hollywood cinema. To engage with Žižek on ideology is therefore to engage with all aspects of life – culture, psychology, love, politics.

Inspired by Karl Marx, Žižek sees ideology as part of what supports a given social, economic and political system. It keeps us doing the things that keep the wheels of the system turning, regardless of what we consciously think. Žižek’s role, as he sees it, is to help bring this ideology to our attention so that we may break free of it. This liberation is essential to the ultimate goal for Žižek: replacing the liberal-capitalist order we currently occupy. To do this, Žižek strives to break the spell of ideology through a kind of psychoanalytic shock therapy that cannot be co-opted by ideological discourse.

“For Žižek, jokes are amusing stories that offer a shortcut to philosophical insight.” (Žižek’s Jokes)

When Žižek affirms Stalinism or prescribes gulags, for example, he isn’t being purely ironic nor purely sincere. His intention is instead to evade the clutches of superficial platitudes that narrow our thinking. In doing so, Žižek wants to “rehabilitate notions of discipline, collective order, subordination, sacrifice” – values that are too easily either neutralised by a bland and inoffensive liberalism that preserves the current social order or demonised via the “standard opposition of freedom and totalitarianism.”

Žižek’s analysis of ideology provides us with some of the tools we need to do this sort of ‘shock-therapy’ for ourselves. He explores the ways in which ideology manages to preserve the system we occupy through such mechanisms as cynicism, “inherent transgression” and the rhetoric of neutrality.

That is, cynicism allows us to knowingly act contradictory to our beliefs with little or no mental anguish.

In this way, the problem is not, as Marx put it in Capital: “They do not know it, but they are doing it.” Rather, it is, to use Žižek’s reformulation:

“They know it, but they are doing it anyway.”

Criticism of capitalism, for example, can thus live quite happily and indefinitely within its inner sanctum, as Hollywood films repeatedly demonstrate. (Here Žižek sometimes likes to cite the 2008 animated film Wall-E).

Žižek continues to be an unpredictable and idiosyncratic voice in politics and culture, difficult to place in partisan terms. Armed with the ferocious joy that he takes in theory and inversion – a joy that opposes all that is easy and superficial – he calls upon us to reflect seriously and radically upon ourselves and our society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Life and Debt

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Power

Ethics Explainer: Power

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 MAR 2022

“If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem. It’s not a question of attitude; it’s a question of power.” – Stokely Carmichael

A central concern of justice is who has power and how they should be allowed to use it. A central concern of the rest of us is how people with power in fact do use it. Both questions have animated ethicists and activists for hundreds of years, and their insights may help us as we try to create a just society.

A classic formulation is given by the eminent sociologist Max Weber, for whom power is “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance”. Michel Foucault, one of the century’s most prominent theorists of power, seems to echo this view: “if we speak of the structures or the mechanisms of power, it is only insofar as we suppose that certain persons exercise power over others”.

A rival view holds that instead of being a relation, power is a resource: like water, food, or money, power is a resource that a particular person or institution can accrue and it can therefore be justly or unjustly distributed. This view has been especially popular among feminist theorists who have used economic models of resource distribution to talk about gendered inequalities in social resources, including and especially power.

Susan Moller Okin is one prominent voice in this tradition:

“When we look seriously at the distribution of such critical social goods as power, self-esteem, opportunities for self-development … we find socially constructed inequalities between them, right down the list”.

What’s the difference between these two views? Why care? One answer is that our efforts to make power more just in society will depend on what kind of thing it is: if it’s a resource, such that problems of unfair power are problems of unequal distribution, we might be able to improve things by removing some power from some people – that way, they would no longer have more than others. This strategy would be less likely to work if power was a relation.

In addition to working out what power is, there are important moral questions about when it can be ethically used. This is a pressing question: As long as we live in societies, under democratic governments, or in states that use police forces and militaries to secure our goals, there will be at least one form of power to which everyone is subject: the power of the state.

The state is one of the only legitimate bearers of the power to use violence. If anyone else uses a weapon or a threat of imprisonment to secure their goals, we think they’re behaving illegitimately, but when the state does these things, we think it is – or can be – legitimate.

Since Plato, democracies have agreed that we need to allow and centralise some coercive power if we are to enforce our laws. Given the state’s unique power to use violence, it’s especially important that that power be just and fair. However, it’s challenging to spell what fair power is inside a democracy or how to design a system that will trend towards exemplifying it.

As Douglas Adams once wrote:

“The major problem with governing people – one of the major problems, for there are many – is that no-one capable of getting themselves elected should on any account be allowed to do the job”.

One recurring question for ‘fairness’ in political power is whether the people governed by the relevant political authority have a to obey that authority. When a state has the power to set laws and enforce them, for instance, does this issue a correlate duty for citizens to obey those laws? The state has duties to its people because it has so much power; but do people have reciprocal duties to their state, also rooted in its power?

Transposing this question into our personal lives, it’s sometimes thought that each of us has a kind of moral power to extract behaviour from others. If you don’t keep your promise, I can blame or sanction you into doing what you said you would. In other words, I can exercise my moral power to make claims of you. Does this sort of power work in the same way as political power? Is it possible for me to abuse my moral power over you; using it in ways that are unjust or unfair – and might you have a duty to obey that moral power?

Finally, we can ask valuable questions about what it is to be powerless. It’s certainly a site of complaint: many of us protest or object when we feel powerless. But how should we best understand it? Is powerlessness about actually being interfered with by others, or simply being susceptible to it, or vulnerable to it? For prominent philosopher Philip Pettit (AC), it’s the latter – to be “unfree” is to be vulnerable or susceptible to the other people’s whims, irrespective of whether they actually use their power against us.

If we want a more ethically ordered society, it’s important to understand how power works – and what goes wrong when it doesn’t.

Join us for the Ethics of Power on Thurs 14 March, 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Who are corporations willing to sacrifice in order to retain their reputation?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Are diversity and inclusion the bedrock of a sound culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How a Shadow Values Review can improve your organisation

How a Shadow Values Review can improve your organisation

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 7 MAR 2022

Michelle Bloom, Director of Consulting and Leadership at The Ethics Centre, discusses the results of Shadow Values Reviews she has conducted for Australian organisations, which reveal and unlock the hidden values that really guide an organisation’s culture.

Shadow Values and principles are an expression of the unstated operating culture of an organisation. Operating beneath the surface, they lie beneath the expressed values and associated behaviours of an organisation. Many organisations, for example state “collaboration” as one of their values which is an effective and positive way to ensure you get the best thinking and diverse perspectives. However, what The Ethics Centre’s Consulting and Leadership team have found is, the value of collaboration is operationalised as “co-operation”, leading to less diversity of thinking and curiosity to explore perspectives. Shadow Values can be even an organisation’s culture as they remain unspoken and out of awareness.

We spoke with Michelle Bloom of the Ethics Centre’s Consulting and Leadership team about the results of Shadow Values Assessments she has done for Australian organisations.

How does a Shadow Values Assessment differ from a traditional staff engagement or culture review?

Most large and medium sized organisations do engagement and culture reviews. Having completed many, with different organisations, we’ve found they’re useful up to a point, usually determined by people’s feeling of psychological safety – the point to which they feel safe to express their actual experience.

We’ve all experienced going through the motions with surveys and being less than forthcoming with our opinions when being asked for feedback, whether that’s because of apathy, fear of reprisal or any number of reasons.

What we’ve done is developed a range of methodologies and approaches to get below the surface of how people feel when they talk about work and build a climate of safety for employees to express their opinions freely without fear of retribution.

This is important because once the skeletons are out of the cupboard, the Shadow Values are all known – they’re understood, people feel a sense of relief and optimism that things can change and change for the better. It’s a different paradigm – this approach is more social science and anthropological, more qualitative than other, more standard culture pulses and staff surveys. It’s more about listening to how people express their experiences, which means they’re inherently more comfortable in having a conversation that’s focused on what matters to them and about how the organisation lives their values and where they don’t.

The approach explores people’s lived experience of the values, and the language people use to describe their perceptions gives you a different depth that you don’t find in other culture reviews. Our culture review provides rich insights into the shadow aspects of the culture which is particularly important is times of rapid change and uncertainty. It is not using benchmarks, often validated in a BAU environment, which give a partial view and less relevant in a VUCA context.

What sort of Shadow Values are exposed by these assessments?

We often find similarities in the Shadow Values raised across different organisations, for instance employees recounting their ability to raise issues, manage up, or quoting expressions such as, “keep your head down” and “don’t rock the boat”. These are very common manifestations of maintaining harmony, avoiding conflict, and just getting your job done.

Our insights provide an understanding of how the different Shadow Values constellate to form patterns of behaviour that support the implementation of strategy (or not). This allows you to see a systemic view of the organisational culture: how to shift, amplify and or re-enforce behaviours in service of living your values, implementing your strategy, and achieving your purpose as an organisation.

People join, stay, perform, or leave organisations based on their experience of the culture and what the organisation says it stands for. If there is a disconnect between the espoused values and purpose and the employees experience of them, it can lead to disengagement, resentment, poor performance and a cynicism impacting both the employee and customer experience.

These systemic insights are a bespoke part of the assessment and what we recommend to one organisation wouldn’t necessarily be the same as what we’d recommend to another. It’s about understanding the social system within the organisation, and each organisation will be quite different based on their shadow values.

How have you seen Shadow Values Assessments make an impact upon clients’ organisations?

Our clients have told us that Shadow Values Reviews have helped them to understand the drivers of behaviour and performance and guided them to intervene at a systemic level to shift these patterns and ways of working. The reviews also help them to understand the shadow values that are not formally codified but are having a very positive impact such as “entrepreneurialism” in one organisation.

Engagement surveys, 360 reviews and culture pulses deliver a very different set of quantitative data to the qualitative information about culture that comes from a Shadow Values Review. A recent client undertook both a traditional staff engagement and a Shadow Values survey to get insight into how to deliver on their strategy.

Another recent client had issues of psychological safety and allegations of harassment despite having policies and procedures in place to protect employees. As we have seen, all too much recently, that what is in the policy may not reflect how people actually behave. When organisations fail to address these Shadow Values, it can be a slippery slope, leading to unthinking practice, ethical failure, and moral injury. When we ignore, and unintentionally collude through fear, by not calling out and reporting behaviour we know are unacceptable.

What we were able to do was create safety for people to be able to discuss these very sensitive issues and share their experiences confidentially, and report back on themes and patterns of behaviour. People put a lot of trust in us and we have the credibility as we are independent and not for profit, which is a key differentiator of The Ethics Centre from other consulting firms.

We made a number of recommendations that the organisation implemented, and as a result the executive feels strongly that they’re able to deal with the issues sensitively and ethically, manage the systemic risk, implement structural changes and build capability to align their ways of working with their purpose, values and principles.

Have you uncovered and rectified any other examples of detrimental Shadow Values?

In another organisation, we identified significant Shadow Values that created internal systems of patronage, where positional power and influence led to unofficial relationships of quid pro quo. It incentivised fostering relationships with people who had positional power, leading to toxic politics and nepotism. It was inherently destabilising, undermining trust and ran contrary to the more formal systems of reward/recognition programs, performance management and remuneration.

As part of our Shadow Values culture review, we make a number of recommendations to support the organisation to transform their culture aligned to their values. Recently we did a follow-up review with an organisation who had implemented all of our recommendations and the feedback was that employees described it as a “new organisation” and a massive shift in their perceptions and experience of the culture. The performance of the organisation also reflects this shift having delivered on its strategy despite the challenging operating environment over the last 2 years and the quality of the relationships with its stakeholders has been key to delivering on this.

The quantitative measures had improved out of the park – some had improved by 300%. The reasons for that were multiple, but they included a focus on ethical leadership recognising and shifting the Shadow Values, and making formal changes to the organisation’s structure and reporting lines.”

What is the end purpose of a Shadow Values Review, as opposed to traditional engagement and culture surveys?

With a Shadow Values Assessment we’re really measuring an organisation against their espoused values – what they say they stand for and what they actually do. In the time of stress and greater complexity that we now find ourselves, recognising shadow values is becoming even more essential to managing, governing and leveraging culture, for greater employee wellbeing and performance.

If an organisation needs to become more agile or customer-centric, understanding its Shadow Values ensures that it really understands how it actually works and will be able to make informed, evidence-based decisions on what they want to do about their culture to change it. Just saying we value something is not enough. Understanding how to be more “agile or customer centric” is key. Simple, traditional approaches and solutions often fail to deliver as they don’t consider the complex social system of the organisation and the eco system in which it operates, that really determines what is valued and what is rewarded, despite what is espoused.

Some riskier elements of organisational culture have emerged recently, in the way values and behaviours are operationalised, often unintentionally but with disastrous impacts on customers, employees and organisational reputation – think Royal Commissions and recent corporate failures. What a Shadow Values Review delivers is a deep insight into your organisational culture, the values and behaviours that drive it, and a roadmap to help navigate in these complex and rapidly changing times.

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Or visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is employee surveillance creepy or clever?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 FEB 2022

Ethics is about engaging in conversations to understand different perspectives and ways in which we can approach the world.

Which means we need a range of people participating in the conversation.

That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Dr Tim Dean as our Senior Philosopher. An award-winning philosopher, writer, speaker and honorary associate with the University of Sydney, Tim has developed and delivered philosophy and emotional intelligence workshops for schools and businesses across Australia and the Asia Pacific, including Meriden and St Mark’s high schools, The School of Life, Small Giants and businesses including Facebook, Commonwealth Bank, Aesop, Merivale and Clayton Utz.

We sat down with Tim to discuss his views on morality, social media, cancel culture and what ethics means to him.

What drew you to the study of philosophy?

Children are natural philosophers, constantly asking “why?” about everything around them. I just never grew out of that tendency, much to the chagrin of my parents and friends. So when I arrived at university, I discovered that philosophy was my natural habitat, furnishing me with tools to ask “why?” better, and revealing the staggering array of answers that other thinkers have offered throughout the ages. It has also helped me to identify a sense of meaning and purpose that drives my work.

What made you pursue the intersection of science and philosophy?

I see science and philosophy as continuous. They are both toolkits for understanding the world around us. In fact, technically, science is a sub-branch of philosophy (even if many scientists might bristle at that idea) that specialises in questions that are able to be investigated using empirical tools, hence its original name of “natural philosophy”. I have been drawn to science as much as philosophy throughout my life, and ended up working as a science writer and editor for over 10 years. And my study of biology and evolution transformed my understanding of morality, which was the subject of my PhD thesis.

How does social media skew our perception of morals?

If you wanted to create a technology that gave a distorted perception of the world, that encouraged bad faith discourse and that promoted friction rather than understanding, you’d be hard pressed to do better than inventing social media. Social media taps into our natural tendencies to create and defend our social identity, it triggers our natural outrage response by feeding us an endless stream of horrific events, it rewards us with greater engagement when we go on the offensive while preventing us from engaging with others in a nuanced way. In short, it pushes our moral buttons, but not in a constructive way. So even though social media can do good, such as by raising awareness of previously marginalised voices and issues, overall I’d call it a net negative for humanity’s moral development.

How do you think the pandemic has changed the way we think about ethics?

The COVID-19 pandemic has both expanded and shrunk our world. On the one hand, lockdowns and border closures have grounded us in our homes and our local communities, which in many cases has been a positive thing, as people get to know their neighbours and look out for each other. But it has also expanded our world as we’ve been stuck behind screens watching a global tragedy unfold, often without any real power to fix it. But it has also made us more sensitive to how our individual actions affect our entire community, and has caused us to think about our obligations to others. In that sense, it has brought ethics to the fore.

Tell us a little about your latest book ‘How We Became Human, And Why We Need to Change’?

I’ve long been fascinated by the story of how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today. Morality has played a key part in that story, helping us to have empathy for others, motivating us to punish wrongdoing and giving us a toolkit of moral norms that can guide our community’s behaviour. But in studying this story of moral evolution, I came to realise that many of the moral tendencies we have and many of the moral rules we’ve inherited were designed in a different time, and they often cause more harm than good in today’s world. My book explores several modern problems, like racism, sexism, religious intolerance and political tribalism, and shows how they are all, in part, products of our evolved nature. I also argue that we need to update our moral toolkit if we want to live and thrive in a modern, globalised and diverse world, and that means letting go of past solutions and inventing new ones.

How do you think the concepts of right and wrong will change in the coming years?

The world is changing faster than ever before. It’s also more diverse and fragmented than ever before. This means that the moral rules that we live by and the values that drive us are also changing faster than ever before – often faster than many people can keep up. Moral change will only continue, especially as new generations challenge the assumptions and discard the moral baggage of past generations. We should expect that many things we took for granted will be challenged in the coming decades. I foresee a huge challenge in bringing people along with moral change rather than leaving them behind.

What are your thoughts on the notion of ‘cancel culture’?

There are no easy answers when it comes to the limits of free speech. We value free speech to the degree that it allows us to engage with new ideas, seek the truth and to be able to express ourselves and hear from others. But that speech comes at a cost, particularly when it allows bad faith speech to spread misinformation, to muddy the truth, or dehumanise others. There are some types of speech that ought to be shut down, but we must be careful how the power to shut down speech is used. In the same way that some speech can be in bad faith, so too can be efforts to shut it down. Some instances of “cancelling” might be warranted, but many are a symptom of mob culture that seeks to silence views the mob opposes rather than prevent bad kinds of speech. Sometimes it’s motivated by a sense that a speaker is not just mistaken but morally corrupt, which prevents people from engaging with them and attempting to change their views. This is why one thing I advocate strongly for is rebuilding social capital, or the trust and respect that enables good faith discourse to occur at all. It’s only when we have that trust and respect that we will be able to engage in good faith rather than feel like we need to resort to cancelling or silencing people.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Ethics is what makes our species unique. No other creature can live alongside and cooperate with other individuals on the scale that we do. This is all made possible by ethics, which is our ability to consider how we ought to behave towards others and what rules we should live by. It’s our superpower, it’s what has enabled our species to spread across the globe. But understanding and engaging with ethics, figuring out our obligations to others, and adapting our sense of right and wrong to a changing world, is our greatest and most enduring challenge as a species.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture