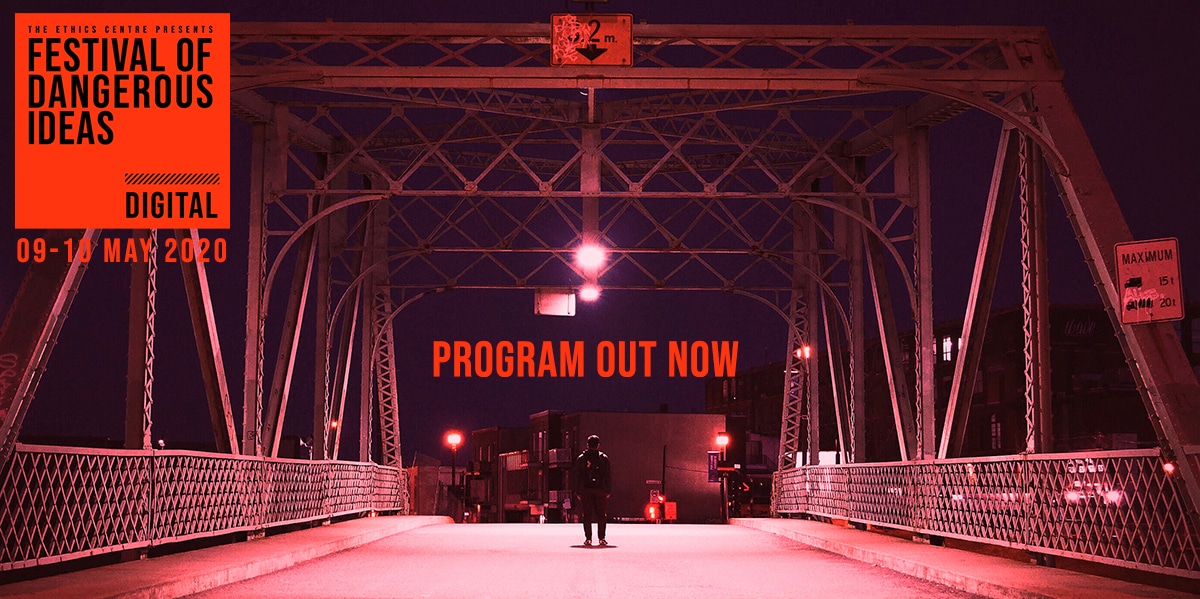

FODI launches free interactive digital series

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

FODI Digital, announced today, is an exciting series of free, online conversations to be live-streamed on May 9 and 10.

The line-up will feature a selection of the international and Australian speakers originally slated for the live festival that was cancelled, by government order, as the COVID-19 lockdown came into effect last month.

“The theme for 2020’s live festival was Dangerous Realities and we seem to well and truly have encountered one. Critical thinking is essential, especially as we isolate further from our communities, families and global neighbours.” said Festival Director, Danielle Harvey.

Executive Director of The Ethics Centre and Co-Founder of FODI Simon Longstaff says FODI digital is a timely invitation to think critically.

“We may submit to a lockdown of our bodies, but never our minds. If ever there was a time to test the boundaries of our thinking … it is today!”

The series of online conversations takes inspiration from the original FODI 2020 theme of ‘Dangerous Realities’, with online sessions being streamed via the festival website. The series will interrogate the reality of the current pandemic and its wider implications for our world and society.

Audiences can contribute questions live while the discussions take place.

For Festival Director Danielle Harvey, there’s never been a more important time for these critical conversations. “Decisions are being made at every level that will shape how we live our lives both now and in the future.

“While we can’t present the program in the way originally planned, these digital conversations will address topics that really need to be put under the microscope. COVID-19 will hopefully end at some point, and understanding what kind of world we will then be entering is essential.”

Sessions include:

- The Truth About China – Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is joined by journalists Peter Hartcher and Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, with Human Rights Watch researcher Yaqiu Wang, and strategist Jason Yat-Sen Li, in a wide-ranging discussion about China;

- The Future Is History – Russian-American journalist, high-profile LGBTQI activist and outspoken critic of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, Masha Gessen, shares her thoughts on Russia and the coming US elections;

- Snap Back To Reality – Philosopher Simon Longstaff leads a discussion with social researcher Rebecca Huntley, political journalist Stan Grant, and fellow philosopher Tim Soutphommasane, on the social shifts, policy and economic consequences that await us in a post-COVID-19 world;

- States of Surveillance – Futurist Mark Pesce, 3A Institute data expert Ellen Broad, and founder of Old Ways, New Angie Abdilla discuss the issue of digital surveillance for virus tracking and the potential threat posed by the ‘normalisation’ of government surveillance;

- Misinformation Is Infectious – First Draft’s Claire Wardle, tech journalist Ariel Bogle discuss COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and what they tell us about technology’s role in the spread of damaging misinformation;

- Stolen Inheritance – Australian youth leaders, Daisy Jeffrey, Audrey Mason-Hyde and Dylan Storer discuss their concerns for the world they will inherit: a world of debt, educational disadvantage, diminished job opportunities, climate catastrophe and … future pandemics;

- The Ethics of the Pandemic – Philosophers Matt Beard, Eleanor Gordon-Smith and Bryan Mukandi take a step back from the day-to-day dilemmas of the pandemic to try to understand what’s really going on, the lessons we learn and the hidden costs of the choices we make;

- Political Correct-Mess – Conservative Australian commentator Kevin Donnelly, journalist Chris Kenny, and journalist Osman Faruqi join journalist Sarah Dingle to dissect political correctness and ask, “Has it gone too far?”;

- Ageing is a Disease – Biologist David Sinclair talks about cracking and reversing the ageing process, which may help the elderly in their fight against a range of diseases and viruses.

The event will live stream straight from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas website across May 9-10. Visit www.festivalofdangerousideas.com to view the program.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Thought experiment: The original position

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 24 APR 2020

A senior executive starts making out-of-character decisions that reflect his personal fears. Teams are frozen in indecision as the ground continually shifts beneath them. Days become punctuated with emotional meltdowns from people you have always relied upon in a crisis.

At home, you might be disagreeing with loved ones about the right response to COVID -19. Is the situation as serious as officials claim? Or are people exaggerating the risks? What is the right amount of physical distancing? Why should the whole of a society bear the costs for the sake of the few? Is this even a fair way to frame the questions?

These are some of the signs that the prolonged impact of COVID-19 is causing moral fatigue in the people around you.

Moral fatigue can occur when the “right thing to do” is unclear. Who should bear the cost of protecting a business? What if personally caring for elderly parents risks exposing them to deadly infection? It can be exhausting to make decisions in this kind of ambiguity, day after day.

Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School, says moral fatigue comes from situations where attempts to do good also result in “destroying a good”.

“People have often referred to the idea of moral fatigue as compassion fatigue or moral distress,” he told me on a zoom call from the US. “What we have in the current context is a situation that makes it increasingly difficult to understand if I’m doing the right thing. It’s no longer possible to assume that the good that I’m doing is unambiguously good,” he says.

It could be dangerous to keep running a business, for instance, if it means employees are in danger. “There’s a real conflict there. And there are no rules.”

Why people panic

Usually, as people go about their normal lives many actions are performed on “autopilot”. Typing on a keyboard, for instance, is done out of habit; the decision of which keys to hit doesn’t exercise mental exertion; one’s finger ‘do the work’. Baur says a crisis such as COVID-19 “jumbles” the keys on the keyboard. It changes the rules and worse still, you don’t know what those new rules are as they can change, minute-by-minute.

“It’s really disorienting,” says Baur. “People go back to what they know is safe, and they become more infantile, more self-protective and defensive.”

This is the kind of response that decreases our capacity to make good decisions. It leads to the hoarding behaviours we have seen in supermarkets, anxiety about money and a focus on individual survival.

Slow down and be more forgiving

Thinking about ‘just getting beyond this’ assumes a future state where the problem no longer exists and everything is the same as before. It’s too simplistic to suggest we will all be ok – many of us won’t be, unless we adapt.

A common result of moral fatigue can be impatience. When we try to think through frameworks that no longer serve us well we can become increasingly impatient, the more we do so, the more mistakes we make – leading to even more frustration.

Baur likens our situation to building the raft at the same time that you are using it to survive. He says, it’s okay to make mistakes because we’re all trying to refashion this raft, even as we’re stepping on top of each other trying to stay afloat. Mistakes will be made.

“You’re not alone. Everybody feels the same way. We have to be more forgiving of others and I think individuals have to be more forgiving of themselves in the sense that it’s okay to be freaked out. Everybody is.”

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 16 APR 2020

The coronavirus pandemic has affected nearly everything we do in our everyday lives. The things that give us joy and meaning – going to the gym, the beach, meeting friends for coffee – are no longer possible.

This is having a real impact on our mental health and capacity for good decision making. Beyond Blue have reported a four-fold increase in the number of calls and enquiries related to COVID-19 since March, a level far exceeding the period during the summer fires.

Our brains are wired to seek certainty and our neural circuits register unexpected events as threats. This triggers a fear response, known commonly as ‘fight or flight’, which causes a cascading chemical reaction in our bodies. That response prevents or impairs access to the higher levels of the brain where we deal with complex decisions.

So, it’s fair to say that uncertainty and fear reduce our capacity for quality decision making. This is, in part, because the area of impeded access involves the pre-frontal cortex, the part of our brain that actively processes information, accesses creative thinking and enables good decision making.

At its very core, ethics is about making good decisions. It asks us to consider all the ways we might act and to choose for the best. To take responsibility for our beliefs and our actions, and live a life that is entirely our own.

We know that many of you are facing challenging choices in circumstances that involve an unprecedented level of change and uncertainty in our individual and collective lives.

People are moving to work from home with kids in the house, facing job losses, closing businesses and deciding how to care for vulnerable loved ones. Many people are also experiencing the impacts of hyper-connection and feeling overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information.

With the sense of control and certainty taken from us, it’s easy for our decisions to be overcome by what we fear. With that in mind, it’s important to make time to find new activities that will help to activate the feel-good chemicals in our brains.

These seven activities can be practised while experiencing physical distancing. They are proven to slow down the stress response and boost your mood.

-

Take a nature break

2,500 years ago, Hippocrates, the Ancient Greek Physician and so-called ‘father of medicine’, said “walking is man’s best medicine”. Having invented the Hippocratic oath, he certainly wouldn’t lie! The moment you step outside the concrete jungle and into nature, your body shows its gratitude by releasing serotonin, a mood-regulating neurotransmitter. We are encouraged to stay at home. But if you have a backyard or nature reserve nearby, take regular breaks from the computer for fresh air or to use these spaces for exercise. Just be mindful to ensure you’re following recommendations and maintaining safe physical distancing in the process.

-

Move your body

Physical exercise acts like a power booster, it increases endorphins, the ‘peptide good guys’ that reduce pain perception and trigger positivity. Literally, happy days. Running and walking are great ways to shift pent-up energy. If you’re in self-isolation, try skip rope, something you could make, at a stretch, with a plastic cord or clothes line. A 32 year old French man ran the entire length of a marathon on his balcony during lockdown! Give yourself a tech-tox and move your body, ideally in nature, even if it’s just for ten minutes.

-

Take a bath

Many people experience a sense of calm around water and it’s no surprise if you consider the fact that our bodies are 60% water, and our brains more than 70%. Both Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine believe that the water element is crucial to rebalancing the body. With many beaches closed, look to what you can do within your own home. Fill up the bathtub and immerse your body in water. To super charge the experience you might even soften the lighting or drop in some essential oils to stimulate your senses.

-

Have a laugh

Laughter triggers the release of dopamine into the brain’s reward centre, giving you a high that lowers stress levels and increases your receptivity to pleasure. What may come as a surprise is that research also suggests that simply anticipating a laugh can have a similarly powerful effect. The expectation of something funny turns on our parasympathetic response system. So, it seems there’s never been a better time to practise your best ‘dad jokes’ on friends or the kids. There’s plenty of funny fodder available on streaming services. Check out Vulture’s list of the 50 best comedies on Netflix.

-

Practice yoga

The benefits of this ancient practise go far beyond the physical. In a yoga class, the combination of breath awareness and asana (postures) act to still the fluctuations of the mind and deepen your mind-body connection. Studies have shown that just a single one-hour yoga class can have a positive biochemical impact on your brain. Regular practise can reduce stress, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder and depression. With traditional classes currently cancelled, many yoga teachers and studios are live streaming offerings, by donation or free of charge, for you to practise from home.

6. Listen to some tunes

Music makes your brain sing. You know that happy rush you get when your favourite song comes on the radio? It’s a chemical romance, one that lets off steam, injects the good vibes and let’s be real, is just a whole lot of fun. When music triggers your pleasure receptors dopamine is released into the striatum, the same part of the brain that responds to sex, chocolate, and is stimulated by artificial narcotics like cocaine. Research has also found that that some music has meditative qualities and can positively impact stress reduction and overall happiness. Fun fact: neuroscientists have found that listening to this song can reduce anxiety by up to 65%.

-

Dance it out

Dancing, like any other physical activity, releases neurotransmitters and endorphins to alleviate stress. Combining the dopamine response stimulated by music with these endorphins has the potential to supercharge your positivity. Plus, it’s almost certain that you’ll laugh along the way. Right now, you really can dance around the house like no one is watching. Prefer company? Have a virtual dance party. Many companies are rolling out video call dance breaks to manage the impacts of social isolation on extroverts in the workforce. Whether you want to do it with work, or friends, it’s easy to set up a time, pick a song, and all jump on a video call to dance it out together.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Explainer: Hedonism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

Moving work online

Moving work online

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Talya Wiseman The Ethics Centre 10 APR 2020

As the COVID-19 dominos continue to fall, many organisations are scrambling to rethink the way they work. These changes are happening in real time; on a scale both unprecedented and unpredicted.

The last pandemic of this nature, the Spanish Flu, occurred 100 years ago – well before anyone had dreamed up the internet, computers and video conferencing. In 2020, advances in technology, such as international flights, have allowed this virus to spread at a much faster rate. However, they have also afforded many organisations the opportunity to pivot their operations online.

Schools and universities have, for the most part, managed this at an incredibly fast pace. With barely any notice, teachers have become adept at using online delivery platforms and are coming up with new ways to engage their students online.

Students are able to continue their same classes via platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams; all the while knowing that the rest of their class is right there, learning alongside them.

Now that all but essential workers are urged to stay at home, ideas about working environments have also been forced to alter at an unusually rapid pace. For example, workplaces and teams have begun to adapt to meeting online. A popular meme doing the rounds at the moment depicts a scenario 40 years from now when a grandchild asks their grandparent with wonder “Go to work? You used to actually GO to work?”

It is incredible to see how many fundamental changes and shifts in thinking have occurred in such a short space of time. We simply had neither the time nor the opportunity to incorporate long policy discussions, carefully timed rollout plans or trial periods. Many organisations that previously assumed they needed a common workplace are now questioning the validity of this assumption.

What happens next?

The big question is this: when all of this is over and we return to normal, what will normal look like? Will organisations revert to their old ways? Or will we have seen the value in new patterns of working? Our eyes have been opened through this experience. Our assumptions about the nature of work have been challenged. Having reorientated towards online workplaces, will it be so easy to pivot back? And will we want to?

There are certainly benefits to workplaces accepting remote working as a viable option. Parents and carers, who previously struggled to convince their employers that they could effectively work from home, will likely find this argument much easier to make. If people have been able to fulfill their work duties in these most trying times, clearly it will be easier for them to continue to do so when it is an option they are choosing.

The stigma of working from home has rapidly been removed. It should no longer be seen as the ‘lesser’ option compared to attending an office. Organisations are finding innovative ways to ensure staff feel supported while working from home; while also maintaining expectations of staff – wherever they happen to be located.

The role of the physical workplace

However, there is a risk in realising just how easy it is to do things online. The role that work plays for individuals is much more than just providing an income. Work is also about fulfilment; it is about social interaction. The best initiatives can arise from bouncing ideas around with colleagues. Families can laugh together at the dinner table when sharing work stories and funny moments that occurred at the office. Colleagues can celebrate each other’s success and commiserate together when things don’t go as planned. Work is about so much more than ‘work.’

One of our principles, here at The Ethics Centre, is to “know your world and know yourself”. We believe in the importance of questioning who we are and being conscious of what we do. If the nature of work is fundamentally to change, we must recognise what we are giving up, as well as the opportunities that may arise. Just because we were rushed into this new reality doesn’t mean we can’t carefully consider the best way to move on from it.

Let’s not just fall back into old patterns. Let’s use this as an opportunity for questioning and for finding a better ‘normal’. That might well be a workplace that embraces flexible arrangements and is open to non-traditional office environments, while at the same time never losing touch with deeply human moments and interactions.

Perhaps we will realise that work, regardless of industry, is about purpose, fulfilment and human interaction.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

BY Talya Wiseman

is an experienced educator who has worked extensively in both the formal and experiential education space. At The Ethics Centre, Talya is the Educational Program Manager creating innovative, engaging and quality ethics-focused education

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Gentilin 9 APR 2020

Crises, especially as momentous as this one, have a habit of exposing leaders. At worst, they expose incompetence and self-interest. At best, they reveal courage, resilience and deep concern for others. It is the latter that is the hallmark of ethical leadership.

Make no mistake, these are challenging times. There are potentially some dark days ahead. Humanity has not faced a perilous situation of this magnitude in my lifetime.

Unfortunately, ethical leadership is not something that can be ‘switched’ on at will. In trying times, one cannot simply dust off the ethical leadership manual and, like a chameleon, transform one’s approach. The reason for this is that ethical leadership is honed through many years of practice.

Ethics is a long game

This is not a new idea. Aristotle described ethical virtue as a “hexis” – a state or disposition – that is shaped by our habits. We come to be ethical by acting ethically, consistently being guided by an ethical framework when making choices, regardless of how difficult this might be given the prevailing circumstances. This is what it means to be a person with integrity.

For this reason the COVID-19 pandemic will (and in some cases already has) reveal what leaders believe to be good (their values) and right (their principles). More importantly, it will reveal how committed they are to their ethical core. Those who have failed to make ethical practice a daily habit will find it difficult. They may already have stumbled or are perhaps struggling to win the trust of sceptical followers. For those who have made integrity central to their leadership, the turbulent waters will be somewhat easier to navigate. Making the ethical choice will come more instinctively.

There is also the possibility that ethical leadership will emerge in the current crisis from the most unlikely of places. People whom we may have thought were not cut out to deal with a crisis or a thrust into a position of leadership will rise to the occasion. Perversely, moments like these, instead of paralysing leaders, can provide greater clarity on what is the ‘right’ thing to do. The path one must take, although rocky, lights up and is clearly signed. A leader comes into their own.

Ethical leadership, not perfection

All this being said, one thing that we should not (and cannot) expect is ethical perfection. In situations like these where there are excruciating trade-offs associated with many decisions, ethical perfection cannot be defined. The available choices are evenly balanced, providing a myriad of possible outcomes that all have considerable merit. It would therefore be preposterous to think that any leader in these circumstances, no matter how ethical, will get everything ‘right’. We should respect those who are being called upon to make extraordinarily difficult decisions, with imperfect information, in a highly dynamic environment.

However, there are some minimal expectations we should expect from our leaders. We should expect a degree of candour and honesty, accepting that in some cases full transparency will do more harm than good. We should expect that the safety of people – particularly the most vulnerable – is prioritised, accepting that there will be unfortunate loss of life. Above all, we should expect leaders to act with sincerity, rely on the best available evidence and display ethical competence. ‘Winging it’, ‘intuition’ and ‘common sense’ are not enough.

We all have a role to play

We should also understand that ethical leadership is not reserved for those who sit highest in the hierarchy, especially in unprecedented moments like these. This is something that can’t be underestimated. Ethical leadership will need to emerge at every level of society if we are to find a way through what will be some very difficult weeks and months ahead. Do not discount our essential role as ethical citizens.

Jon Haidt, a professor of ethical leadership at the Stern School of Business at NYU, talks about how morality “blinds and binds”. It can evoke the passions and bind people around a common cause. However, in doing so, it can breed dogmatism and drive us into our ideological camps, blinding us to our common humanity.

For the first time in a while, the coronavirus has created a present and common cause that all of humanity can bind to. It will test our leaders and in doing so reveal those who make ethics more than a word in their by-line. It will produce benevolent and heroic acts among citizens that extreme circumstances like these so often educe. And hopefully, by producing a cause we can all be bound by, it will dampen some of the tribalism and self-interest that has been an unfortunate feature of some sectors of our society in recent times.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

When you hire a philosopher as your ethicist, you are getting a unicorn

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do Australian corporations have the courage to rebuild public trust?

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics at Work, a 2018 Survey of Employees

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

360° reviews days are numbered

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 9 APR 2020

You’ve been hitting us up with your COVID-19 ethical questions. We’ve been sending our ethicists into the philosophy lab to cook up some answers.

This week, we’re talking about trade-offs. How do we the balance risks and potential harms from our behaviours against the value they might have?

I have family members who are at high-risk from COVID-19 but who are also at risk of mental stress from isolation, what should I prioritise – their physical safety or their psychological wellbeing?

When I was teaching medical students (about ethics, nobody wants me teaching them science), I was often relieved to find an openness to considering the holistic needs of the patient. They weren’t interested in healing the body at the expense of the mind. This was thanks in part to something called the ‘biopsychosocial model of health’, which basically suggests that we need to think of health at the intersection of the physical body, the mind and the environment we find ourselves in.

What this model reminds us of is that we don’t make trades between mental and physical health – those terms are somewhat of a misnomer. There aren’t different kinds of health; there’s just health. Someone who is suffering from a virus isn’t enjoying a healthy life; nor is someone whose depression is worsening as a result of isolation.

Think about it this way: if your family members were diabetic and needed to go to the pharmacy to fill their insulin prescription, you wouldn’t advise them not to go because they were high risk of COVID-19; because that’s not the only thing that’s going to set back their health. I’m not convinced you should think about their health any differently because the problem is mental rather than physical.

That said, it’s important to bear in mind that you should still do what you can to minimise the risk to your family members – not least because they may not be the only ones who are at increased risk of infection if you choose to visit. Again, think of the diabetes analogy. It would be unreasonable to tell them not to go to the pharmacy for fear of COVID-19, but it would be safer if someone who wasn’t high risk collected their prescription on their behalf.

By the same logic, if there are ways you can alleviate their sense of loneliness and isolation without increasing their risk, then you should do those things. You might not have to choose between minimising the risk of infection and helping a lonely family member at a time when loneliness is rife. But if you can’t, it’s helpful to remember that you’re dealing with risky options either way.

I’m struggling to decide whether I should visit my two loved ones in their aged care facilities right now. Do I leave them and trust they will get the correct care if the outbreak spreads or ‘check in’ and visit them?

Ever heard the story of the two wolves? It’s an old proverb. A Native American elder explains to a young man that there are two wolves inside us all. One represents the lesser demons of our nature, and the other the better angels. The wolves are in constant battle with one another to determine the kind of person we’ll be. ‘Which wolf wins?’, asks the young man. The elder responds, ‘the one you feed.’

In times of enormous stress and uncertainty, the two wolves duking it out inside us tend to be our attitudes toward control. One wolf screams ‘Jesus take the wheel!’ and surrenders all sense of agency – throwing in the towel and hoping for the best, taking no responsibility for the future. The other wolf cries, ‘let me drive!’ and tries to manage every possible variable to secure a half-decent outcome. And, just like the story goes, the wolf we feed – the one we reinforce through behaviour and habit – is the one that will win out.

The reason I share the story of the wolves with you is because your concern for loved ones doesn’t seem to be primarily about giving them social connection or making sure they’re not lonely. Rather, your question suggests what’s bothering you most is whether the carers will do a good job without you to check in. That kind of distrust is likely the product of one of two things: reason or anxiety.

Do you have reasons why you suspect the care for your loved ones will languish in your absence? If so, I can only imagine how heart-wrenching it must be to stay away at a time like this. However, if you’ve generally had good experiences and haven’t had any reason to distrust the staff until now, it’s worth reflecting on whether your inner micro-managerial wolf needs some time off to meditate.

I mean that sincerely – most of us need to meditate during this pandemic – to get clarity on how we manage uncertainty. Do we have trouble accepting our lack of control? Are we too lackadaisical or passive when shit hits the fan?

The truth is, I can’t answer the question of whether you should check in on your family – and in doing so expose them and everyone else at those aged care facilities – because I don’t know if you’ve got good reasons for concern. But let me plead with you on behalf of every person who has loved ones in aged care: if you’re doing this because you’re anxious and scared, please stay at home. We’re all scared for our loved ones, but hopefully you can see that resolving that fear by exposing the people you love to risk is as pointless as howling at the moon.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Michelle Bloom The Ethics Centre 6 APR 2020

COVID-19 has created a cascade of unprecedented changes to how we work, live and interact.

With many organisations moving online, managing restructures, significant job loss and transformation of existing roles and responsibilities, leaders need to be consciously aware of the impact of stress on individual and team performance.

Certain aspects of organisational behaviour can trigger threat reactions in people that impede their effectiveness and limit their ability to contribute to the success of the team. Research in neuroscience can inform our response to such situations, as the neural functioning of individuals within the workplace underlies the social nature of high performance.

What happens to us in stressful environments

The brain is a social organ. Studies by UCLA have found that when we feel excluded from play or rewards, our brains trigger a response from the same neural regions associated with the distress that comes with physical pain. This neurophysiological link has been explained as evolutionary, a developmental hangover from the dependency of infancy. As UCLA neuroscientist Matthew Liebermann puts it, “To a mammal, being socially connected to caregivers is necessary for survival”.

This neurological response has a number of implications for business and leaders navigating this current crisis – especially in regards to remote working and communicating organisational changes driven by COVID-19.

A person who feels their position and work to be valued, by their leaders, solely as an economic and rational transaction (labour for money) will likely feel betrayed, unrecognised and disengaged.

Research shows that each time a person feels like this, it is physiologically and psychologically analogous to a ‘blow to the head’ and is processed in the brain in the same way as physical pain. Naturally, our conscious selves rationalise the discomfort, but if this situation is chronic and ongoing, it is more likely that employees will begin to desensitise in self-protection. They will effectively push the discomfort away, so as to not feel it consciously. This shutting down of large parts of our response pathways disables us, making high-performance impossible.

Many studies, including Paul MacLean’s infamous “Triune Brain” theory, look at how fear responses negatively impact the quality of mental functioning. In more mild circumstances, the emotional centres associated with the limbic brain will interfere with the circuitry of the logical neo-cortex. In extreme circumstances, our ‘fight, flight, freeze’ response gets triggered, creating a chemical reaction that entirely hijacks the brain’s emotional centre, the amygdala, making logical thinking impossible.

However you conceptualise it, high emotion is disastrous for the adaptive thinking required for complex problems – so critical for ethical decision making.

Physiologically, the threat response ties up glucose and oxygen, as lower areas of the brain, more intimately concerned with survival, take precedence over higher centres. In threat situations, these resources are withheld from working memory, impairing the processing of new information or ideas, and slowing analytic thinking, creativity and problem solving.

Addressing the needs of the individual and the organisation

We’ve all heard that adults are poor learners, fundamentally intractable, or that their natural response to change is resistance. While elements of these statements are true, what is also true is that the adult brain continues to be highly plastic; albeit not as much as children or infants. That means that not only can behaviours change, but that the neural networks that underlie all thought and behaviour are in fact changing every day.

To increase the chances of your business being high-performing, David Rock’s SCARF Model, as outlined in his paper “SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating with and Influencing Others,” suggests that leaders should look at how the organisation deals with the following aspects of individual functioning in the collective social system.

1. Certainty

Our brains are wired to crave certainty. This desire is underpinned by neural circuits that register unexpected events as gaps or errors. Because an assumed pattern is no longer functioning as it should, it is registered as a threat.

Think about how you respond when the car in front slams on the brakes. Normally, we can do multiple things at the same time when we drive – hold a conversation, listen to music, monitor what’s going on around us, think about the shopping list – but faced with a potential accident, your working memory is diminished. All other activities and thoughts must cease as you shift full attention to the potential threat ahead.

Some uncertainty can be intriguing and enjoyable; too much leads to panic and bad decisions. For many people right now, the levels of uncertainty – combined with imminent health and employment risks – will be triggering this aspect of the ‘fight or flight’ response. This impedes their capacity to access creative thinking and good decision making.

Of course, certainty is an illusion. However, people need a semblance of certainty in order to perform. Leaders need to build confidence in their people so they, in turn, can trust in individual and collective capability to work through whatever comes. Keeping a clear and regular stream of communication around how decisions are being made increases trust and promotes engagement. Chunking larger problems into shorter time frames also helps people feel more certain.

2. Status

As humans, our relative status within social systems matters. This is the basis for all competition, social hierarchy, and, conversely, much social unrest. Many organisations have processes and practices that threaten people’s status. Hierarchy reinforces a notion of ‘greater than’ and ‘less than’, while performance appraisals and coaching generally place one person in the position of being more knowledgeable, capable and powerful than the other. Unless these interactions are carefully considered and thoughtfully executed, they will feel threatening to an individual’s status.

Actions that enhance status include private, as well as public, recognition. In addition, the quality of interactions from leaders with their people can raise the self-status of those who sit lower in the hierarchy. Therefore, one of the most important (albeit intangible) skills of a leadership team is their capacity to interact with others in a respectful and status-enhancing way.

With staff working digitally, and from home, leaders need to innovate and find new ways to show this recognition. This will make people feel seen and valued for the work they do.

3. Autonomy

When people feel they can execute their own decisions, without interference, their felt stress is lower. In a 1977 study, residents of aged care facilities who had more agency and decision making rights, lived longer and healthier lives. While what they were deciding about was insignificant; their autonomy was critical. In another study, franchise owners principally left corporations citing work-life balance. Once in their own business, they generally worked longer hours, for less money, and nevertheless reported better work-life balance, because they were making their own decisions.

Delegation systems, hierarchy, confusing reporting lines, moribund policy and procedure, and parochial mindsets can all contribute to less agency for individuals in businesses. Often people are not aware that they are not delegating, that they are effectively withholding decision making from others.

Lack of autonomy is also closely linked with the phenomena of people not working ‘at the right level’. When leaders find themselves working at a level of complexity lower than where they should be working, the flow on to the rest of the organisation is usually inevitable.

4. Relationships

Perceived difference is another human threat-trigger. Collaboration, trust and empathy are predicated on perceiving that the ‘other’ is from the same social group as we are. The decision of friend or foe is usually made in milliseconds.

The organisational implications for bringing groups together are profound. Forming new relationships at this time, such as buddy systems or mentor programs, need to be carefully thought through so as to minimise the potential to ‘spook the horses’. The creation of productive strategic relationships requires repetition via multiple, sequential opportunities and reinforcement through the removal of organisational impediments.

5. Fairness

Fairness is a cognitive construct that motivates people so strongly they will persist in situations that are manifestly unfavourable because they value a perceived fairness on the part of an organisation or a cause. Consider how people historically have volunteered to fight in wars that are not their own, such as the Spanish Civil War, and are prepared to die based on apparent fairness.

People not only want to avoid being unfairly discriminated against, they will also often feel uncomfortable if they find themselves being unfairly favoured by a person or a situation.

Organisationally, the implications are similar and connected to that of certainty. People will be much more accepting of decisions and processes, as fair, if they are transparent.

Fairness is also related to status in that people will feel fairly dealt with if they perceive they are respected as a person and employee. These principles are often coded as ‘natural justice’. In some ways, fairness is an amalgam of the previous four areas of concern.

What leaders need to think about

The upshot for leaders is this – when you trigger a threat response in others, you make them less effective. When you make people feel good about themselves, clearly communicate your expectations and give agency through appropriate delegations, people feel a reward response which is intrinsically engaging – something your people want more of.

In situations where threat is felt to be ongoing, people typically experience burnout. This emotional exhaustion is a result of chronic over-stimulation of the fear centres of the brain. Physiologically, high levels of adrenalin and cortisol can only be supported for so long before they start to damage the nervous system.

Where these sorts of threatening social conditions are widespread, ongoing or both, each individual’s sub-optimal reaction is reinforced by the reactions of the people around them, magnifying the pattern. This looks like ‘learned helplessness’, passivity or protective withdrawal. Sometimes it drives an aggressive pattern where individuals seek authoritarian control over whatever small part of their world they feel they can have an effect on.

Practical steps that can be taken during COVID-19

If you’re an organisation transitioning working roles or letting go of staff due to the impacts of COVID closures, ensure you are both transparent and compassionate in your communications.

Be clear and straight forward about how government policy impacts your workers, keep them informed of the decisions being made and communicate the rationale behind them, particularly when they impact others.

When communicating changes, respect for the people affected is crucial. While your decisions have economic drivers, there are very real human costs associated with the outcomes.

Relationships and connection are of heightened importance now. Take care in implementing processes to foster positive relationships between people – whether by virtual catch ups, a mentor support system, or regular virtual check ins by managers with their staff to see how they are coping and adjusting.

Tension will also be high, and any perceived difference may trigger as a threat. Leaders will need to be conscious of how relationships are managed between staff who may be actively competing for scarce resources or roles, if facing redundancies.

None of these strategies ameliorates the situation

It is the responsibility of the leaders of the transformation to monitor if what is going on in their organisation is supporting or undermining people’s performance. If performance is being undermined, it is their responsibility to raise those instances to awareness of their peers in the leadership team, to mobilise and support staff to break the prevailing patterns and to experiment with alternative approaches.

Navigating the changes ahead won’t be easy, and for many this may be the hardest professional challenge they’ve had to face given the stakes have never been so high. But careful attention to how decisions are made and communicated is critical to staff safety and wellbeing in the current climate. And that’s never been more important.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The virtues of Christmas

BY Michelle Bloom

Michelle Bloom is the Director of Consulting and Leadership at The Ethics Centre. Drawing on 30 years as a consultant, clinician, and organisational development specialist, she has worked with Australia’s largest organisations in developing and delivering solutions to assess and build value-driven leaders and cultures.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 3 APR 2020

Imagine a parallel universe somewhere, one without a pandemic. What would you be spending this week concerned with? What social and political issues would you be wrestling with? How would you be spending your day?

Ironically, my parallel life looks very similar. Locked in a room, thinking a lot about pandemics. I’m not an epidemiologist or a public health expert though – in my parallel universe, I’m preparing to run a thought experiment for The Festival of Dangerous Ideas: The Ethics of the Apocalypse.

The basic premise is to find out whether, facing a couple of end-of-the-world scenarios, the audience can save the human race without losing their humanity in the process. I won’t give away how the event works or is scored, but there are a bunch of different victory conditions – survival is a necessary condition of success, but alone, it’s not sufficient.

That point bears repeating as we live through a pandemic of our very own: survival is a necessary, but insufficient condition for success.

By focusing solely on what is going to guarantee success or best facilitate a flattening of the curve and minimise deaths, we risk permitting a political and social environment that we would, in that parallel universe, reject outright.

Over the last few weeks, as Australia’s containment measures around COVID-19 have grown increasingly strict, there’s been a widespread movement demanding an immediate lockdown. #Lockusdown and other variations have trended on Twitter, and major mastheads have called for increasingly severe policing measures to manage the pandemic. Writing for The Guardian, Grattan Institute CEO John Daley wrote:

“There is no point trying to finesse which strategies work best; instead the imperative would be to implement as many as possible at once, including closing schools, universities, colleges, public transport and non-essential retail, and confining people to their homes as much as possible.

Police should visibly enforce the lockdown, and all confirmed cases should be housed in government-controlled facilities. This might seem unimaginable, but it is exactly what has already happened in China, South Korea and Italy.”

Similar comments have been made by other public commentators in support of such measures, including the ABC’s Norman Swan. Swan has pointed to the efficiency with which China were able to control the spread through draconian measures – including in one case, welding people inside their apartment building.

Imagine in a pre-COVID world, suggesting a liberal democracy like Australia look to the authoritarian state of China for political guidance. Yet, this is what happens when we reduce all things to a single metric: the goal of keeping people at home and flattening the curve of new infections. It is easy to conceptualise. We can visualise what it involves and we can imagine the benefits it confers.

However, whilst this logic is comforting – especially in times when fear and uncertainty are rife – it places us dangerously close to the crude and morally repugnant catch cry: the ends justify the means.

In NSW, new laws and extreme penalties aim to enforce self-isolation regimes – as John Daley’s piece suggested. The maximum penalties for leaving your home without a reasonable excuse (of which sixteen are listed) are six months imprisonment or a fine of up to $11,000.

Are you cooped up in your share house, finding it impossible to work? If you choose to go to the park, you’ll face a severe penalty. Considering using the time your teenager has off school to rack up some learner driving hours by leaving the city and heading to the mountains for a bushwalk? Want to do a drive-by birthday celebration in lieu of an actual party? All of them are now subject to police enforcement. Do any of them, and you’re potentially breaking the law.

There are still those who will argue that it’s good these activities have been made illegal. After all, if you go to the park and sit at a bench, you might pick up coronavirus from someone who was just sitting there, or leave some behind for somebody else. If you go for a drive, you may need to stop for petrol, or break down and need mechanical assistance… more exposures means more risk for vulnerable Australians. The elderly, those with chronic illness, Indigenous Australians and immunocompromised people might be more at risk if you do this. However, it doesn’t follow from this that we should threaten people with prison sentences for failing to play ball.

In suspending our ordinary ways of life, we don’t also suspend the moral norms and ethical principles that give them direction and meaning. Punishments should still be reasonable and proportionate to the offenses; we should still aim to strike a reasonable balance between risk, security and freedom.

As Schwatz Media’s Osman Faruqi – who has been following the authoritarian developments around COVID-19 management – noted ,we should remember that increased law enforcement itself carries a cost. Whilst we’re all equal before the law in principle, in practice, minority communities, the poor, homeless and a range of other groups – vulnerable Australians – tend to bear the brunt of increased police activity around the world.

Police have been encouraged to use their discretion in enforcing these laws, but discretion is subject to bias and inconsistency, as is any other aspect of our decision-making. If new police powers are necessary to protect vulnerable Australians from COVID-19, who will be protecting the Australians made vulnerable by these new laws?

In the best-selling board game, Pandemic: Legacy, players have to combat a fast-evolving, unknown virus, using various measures. Options range from quarantines to military lockdowns to the literal, nuclear option. However, because the goal of the game is simply to ensure humanity’s survival and the effective control of the pandemic, these options are all seen as morally equal.

In a game, that’s fine. In reality, as we go from suspending ordinary life to suspending more basic moral and political norms and rights, we need to be able to understand and consider the costs it involves. We can’t do that if our sole metric for success is flattening the curve.

In his column, John Daley wrote that “Covid-19 is the real-life “trolley problem” in which someone is asked to choose between killing a few or killing many.” This framing only obfuscates the deeper issues which pit health and safety against other essential political values; short-term outcomes against a long-term political landscape and the competing needs of different of vulnerable communities.

That’s not a simple trolley problem, it’s a political smorgasbord. And we need a much more sophisticated scoring system to work out what success looks like.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Learning risk management from Harambe

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

This isn't home schooling, it's crisis schooling

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Talya Wiseman The Ethics Centre 1 APR 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken a way of life we previously took for granted – going to work, celebrating weddings, seeing friends and wandering aimlessly down fully-stocked supermarket aisles.

However, one of the biggest changes for many parents is that kids are being urged to stay home unless it is absolutely essential they go to school. Overnight, parents have had to become teachers, along with everything else they are attempting to squeeze into already overfilled schedules.

Where a few weeks ago home schooling was a vague and unfamiliar concept, it’s now become the norm. Parents are scrambling to find a new routine where kids are at home while continuing their education.

As a parent, former school teacher and professional educator who now runs The Ethics Centre’s education programs from my lounge room – with two young kids and a husband in the same room – I’m struggling to do the same.

The juggle of schooling at home

What’s happening here is not home schooling, it’s crisis schooling. Parents who home school have made a conscious decision to educate their child at home. Those parents have spent time organising their resources and routines, deliberating over how to ensure an optimal learning environment for their child, specific to their own needs. Home school parents often have networks of other parents who have also chosen this option, and together, they collaborate and socialise their children.

Crisis schooling is different. With very little notice or choice, suddenly kids are home. Crisis schooling has opened a range of dilemmas which parents are now facing, including:

- “How do I prioritise between helping my child learn and continuing to do my job?”

- “I’ve always tried to teach my kids health and fitness and limit screen time, but giving my child a device is now the only way I get a break.”

- “My wife and I are both working full time while the kids are at home, which one of us must sacrifice our work time to learn with the children?”

So how do we navigate these new challenges?

As we often teach in workshops at The Ethics Centre, there are no ready-made answers to ethical challenges. Instead, we have to respond to the circumstances and relationships at play – which will be different for each of us – and try to balance these with our personal ethics; our purpose, values and principles.

It may help to keep in mind some advice from Greek philosopher, Socrates, who maintained that in order for education to occur a person must accept what they do not know. Parents don’t know how to be teachers, except for those who are trained to be so. Let’s not pretend to ourselves or our kids that we’re fully equipped to do this. We’re not.

As parents, we can use the resources that teachers have readily made available. We can admit to our children that there are some things that we don’t know how to do, and that we need to figure it out together.

What we can control

What parents do know is how to love and care for their children. Parents understand their children better than anyone else in the world and can provide them with the love and support they need. During this incredibly uncertain and anxious time, that really is their most important need. Rather than being overly concerned with how much they are learning, whether or not they’re reading enough, practicing fractions or working on their fine motor skills, let’s focus on our children’s mental wellbeing.

The world is a stressful place right now and anxiety is contagious. Children need to feel supported and comforted. Home is supposed to be a safe space for children, regardless of what is happening outside in the world, and this applies today, more than ever.

So, let’s throw out the rule book on schooling. Let’s remember we are in crisis and although we have moved rapidly to this point, we do not have to adjust with the same speed to a new home-based education system. Do what feels right for your family, even if that means throwing out the schedule. Try not to compare what you are doing to others posting about their experience on social media. What works for one family, might not work for yours.

Human beings are incredibly resilient, children especially so. We’ll all adapt. One day soon, normal life will resume – with a much greater appreciation for the things we took for granted before. What our kids will remember is the extra time they got to spend with their parents; the extra cuddles, the extra stories.

Right now, let’s all take a deep breath and cherish the closeness that comes with distancing.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

BY Talya Wiseman

is an experienced educator who has worked extensively in both the formal and experiential education space. At The Ethics Centre, Talya is the Educational Program Manager creating innovative, engaging and quality ethics-focused education

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 30 MAR 2020

You’ve been hitting us up with your COVID-19 ethical questions. We’ve been sending our ethicists into the philosophy lab to cook up some answers.

This week, we’re tackling how to deal with people who you don’t think are doing their bit to socially isolate and help restrict the spread of coronavirus.

How do I talk to loved ones who have a ’this won’t stop me living’ attitude to staying at home?

There’s a quote I’ve seen floating around social media lately that comes from British author, CS Lewis. It’s from his reflections on living in the age of the atomic bomb, but plenty of people seem to be seeing a link between it and the current crisis. It’s a chunky quote, but this part gets to the gist of it:

If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.

Lewis’ message is being shared as one of defiance: better to die on our feet than live on our knees. Don’t let the fear of a microbe stop us from doing the things that define meaningful life. I reckon some of your loved ones would happily share this quote on their Insta Stories if given the chance.

I’m also very confident that Lewis would be livid at the use of his quote in the context of the current pandemic. There’s a big difference between living through the threat of nuclear bombs – where you have little to no ability to affect what happens – and living through a pandemic where each of our individual actions make a real difference between life and death. I promise you this: if Lewis had thought there was something people could have done to stop an atomic bomb from killing them, he would have advised them to do that. Indeed, Lewis himself willingly lived on limited rations during WWII – not the kind of behaviour for someone who thinks we should live it up in the face of death.

But there is a way of reading Lewis’ quote that is helpful in the COVID-19 pandemic, and which might help you navigate your loved ones’ mindset. We should read Lewis’ quote as an encouragement not to let our external circumstances dictate our happiness. Rather than seeing ourselves as ‘waiting out’ the coronavirus, or living in fear of infection, perhaps it is helpful to keep living – just doing so indoors.

I’ve seen plenty of people suggest that they’ve cancelled screen limits on their phones so they can continually check live updates on the coronavirus issue. It’s tempting for it to be the only thing we talk or think about. It’s dominated most of my group chats for the last month. And here’s where we need to ask: is this really living? Wouldn’t it be better to go about our days as best we can in isolation, knowing we’d done all in our power to address the pandemic – and have made the most of life – rather sit in fear and anxiety?

Your loved ones need to get the message that nobody wants them to stop living: they just want to stop other people from dying. But the rest of us need to remember that life hasn’t stopped: there’s meaning, connection and value all around us – if we can just turn away from the fear and see it.

My flat-mate/parents/family aren’t observing physical distancing. I’m so worried, but they won’t stop. What do I do?

If you follow the advice of some politicians, you might consider reporting your flat-mates to the police. However, I’m not convinced that’s great advice for several reasons which I’ll come back to.

In situations where we witness someone else doing the wrong thing, it’s worth being aware of how our biases can kick in and cloud our judgement. We’ll often infer from someone’s behaviour the worst possible intentions.

Let’s say we see someone walk past a homeless person without even looking at them. It’s likely we’ll assume they’re callous or cold, rather than that, perhaps, they just didn’t see them. By contrast, if we did the same thing, we’d know whether or not we were being callous, because the only minds we can truly read are our own.

What this suggests is that you should begin by engaging from a position of curiosity. Do those not observing physical distancing actually know the rules? They certainly should, and ignorance isn’t an excuse at this point – being a good citizen and neighbour means knowing what we need to do to protect people – but if their behaviour is coming from ignorance, the solution might be easy: inform them.

Of course, there are plenty of people who know what they should do, and just don’t care. Here’s where things get tricky – especially if you’re outnumbered – because it’s very hard to persuade someone to be altruistic when they’re fundamentally motivated by self-interest. You’ve either got to convert them into a much more empathetic person or target their selfishness. The former is a long game; the latter is fraught with risk.

For instance, you might threaten to report them to the police if they keep flouting the rules. However, not only might that be a disproportionate response, it also robs your household of the community and solidarity that you’re probably going to rely on to get through isolation.

One possible solution is to leverage the power of shame. We’re social animals – desperate for inclusion and acceptance. If you can show these people how at odds their behaviour is with social expectations and norms, that will create a powerful impulse in them to self-correct. We don’t like doing things that might cause us to be ostracised – that’s probably the reason you haven’t spoken up until now.

But if you can harness the collective moral expectation for people to socially distance from one another, if you can show them that their behaviour makes them a pariah in the eyes of the community, you might find they change their behaviour on their own, and learn something in the process.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships