Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 10 MAY 2022

Yellowjackets, with its widely acclaimed first season, has a more disturbing element than its surface of considerable violence and horror.

Sure, the Showtime series, which follows a group of young athletes as they crash-land following a disastrous plane trip in the middle of the wilderness and turn, with visceral, enjoyable brevity, to cannibalism and taboo-shattering behaviour, contains a lot in the way of gore. There are broken limbs; bodies eating up bodies; physically construed nightmares which the protagonists cannot escape.

But underneath that immediate level of violence is a claim, considerably more unsettling than fractured calcium, that our ethical systems are far from stable and robust. We’re not bent towards virtue. We seem to be shaped in the opposite way. Yellowjackets knows that. And more than that, the show loves it.

Corruption Seeps In, Naturally

Yellowjacket’s “heroes” – a word which only means to indicate those characters who are applied with a particular, and frequently intense, narrative scrutiny – are the stereotypes of “ordinary” people. The show, which flips back and forth between the present and the deep, traumatic past, makes a great deal of effort to depict that. There are extended shots of the central characters, moving their way through the world, not even thinking about the trauma they inflicted on others, deep in their pasts.

Indeed, the flashback structure of proceedings, one that allows the central mystery to unfurl slowly – who ate who, following that terrible plane crash? – mines much from the main characters’ attempts to live their lives freely in the aftermath of their great collectively-constructed horror.

In the show’s temporal present, these plane crash survivors are all people who wake up every day, and apply themselves to their jobs, and are loved and love in turn. You’d meet them, and catch their eyes in a shopping centre, and smile, astonishingly oblivious of their histories. It’s only when we get painful stabs of their past, unfolded in flashback, that we come to understand that there is something hiding here; a history streaked by vicious behaviour.

That “something” can’t be pinned down to the specifics of our heroes’ lives, either. We can’t shirk the implication that we’d fail to avoid the same behaviour – it is nothing less than the human capacity for violence. We are all confronted, more frequently than we would like to admit, with the idea that we have a potential for evil.

Remember that time you stood on the train platform, and considered, all of a sudden, pushing a stranger onto the tracks? Not for any reason – just because you could. Because, despite what we hope ethics might teach us, there’s something actively joyful about vicious behaviour.

Yellowjackets doesn’t make anything extraordinary out of its central characters. These are just human beings, ones who happen to have been freed – predictably, almost boringly – from the social code of morality, and plunged into horror. We all could be there. All that Yellowjackets tells us is that, most worrying of all, we would enjoy it.

So Why?

The philosopher David Hume constructed his ethical system out of twin poles: pleasure and pain. Hume believed that we all have a natural repulsion to pain, and an attraction to pleasure. That, for him, was the foundation of all ethical behaviour, the starting point that explains empathy, charity, and goodness.

Yellowjackets tells us that’s not true. The show’s spark of originality is not to prove that we all have a propensity for inflicting suffering. That’s already been explored through multiple works of art – consider, for example, the Netflix smash hit Squid Game, which should be considered the contemporary final word on what happens when you guide desperate people towards viciousness.

No. What makes Yellowjackets special is that its central characters have spent the rest of their lives following the plane crash pursuing the highs of gnawing on another human being. They’re not tortured – they’re hungry.

We Do What We Want – Thank God

If that sounds horrifically bleak, it’s because, despite its considerable vein of humour, Yellowjackets is horrifically bleak. We are inundated with art that aims to provide us with a moral compass, designating bad and good behaviour, and telling us how to navigate both. The thematic work, quite often, in these pieces of popular culture, is to condition us emotionally – to train us to be repulsed by horror, and drawn to goodness.

Yellowjackets does not do this. It makes the horrendous appear attractive: “look at these regular people, who ate one another, and defied the social norm, and found themselves in the process.” And it makes the virtuous seem weak: “look at those fools who let their sense of goodness stop them from doing what they want to do.”

If there’s any hope here, then, it’s our capacity to understand pleasure and pain in a more complicated way than Hume did, and that much contemporary art concerned with morality encourages us to do so. Rather than monoliths of feeling – this is pleasurable, and thus morally good; this is not pleasurable, and thus morally bad – Yellowjackets encourages us to mine the depth of our affect, and see it as being filled with nuance.

As Yellowjackets teaches us, we can’t hope that we will have an intrinsic and affective pull away from vicious behaviour, and a pull towards virtuous behaviour. What we can hope, instead, is that we understand our emotional states of pleasure and pain as containing more complexity than mere repulsion and attraction. We should become the experts in our own emotional states – not merely how they feel, but how they tell us to act.

After all, as plane crash victims who begin gnawing on each other’s bones tell us – not to mention addicts, or those who hurt the people they love – we can sink, pleasurably, into horror, and feel good about things that we don’t like, or no longer want to do.

We will never extinguish the joy of doing something we know we shouldn’t do. That’s the kid peeking at the Christmas presents before he should; of turning to our friend, maimed in a plane crash, and eyeing up their naked leg, considering our teeth in it. But what we can do is explore those feelings, and truly feel their complexity, and understand that no affect leads us more closely to one conclusion than any other. It’s up to us. That’s scary. But it’s also beautiful.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Let the sunshine in: The pitfalls of radical transparency

Let the sunshine in: The pitfalls of radical transparency

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Tim Dean 3 MAY 2022

“Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.” So wrote United States Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, in his 1914 book critical of the concentration of power in banks and financial institutions, Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It.

Over a century later, sunlight is experiencing a resurgence in popularity as a disinfectant through the concept of radical transparency. This movement towards greater transparency is increasingly being adopted by a wide range of businesses from the technology, legal and environmental sectors as well as the banking and finance sector that motivated Brandeis’ book.

The movement has received a surge of attention in recent years due to policies promoted by pioneers like Ray Dalio, the founder of asset management firm Bridgewater Associates. Dalio sought to improve decision making by encouraging all employees to express their opinions freely about all aspects of the business, creating what he calls an “idea meritocracy”, where the best ideas rise to the surface.

Other pioneers include the US media streaming company, Netflix, and Finnish software consultancy, Reaktor, both of which have implemented wide ranging radical transparency policies covering everything from wage transparency to radical candour in internal communications to releasing employee emails to the public.

And the idea is growing in its appeal. The 2018 Future of Work Study, commissioned by online communications platform Slack, found that “80% of workers want to know more about how decisions are made in their organization and 87% want their future company to be transparent”.

However, there’s no single definition or implementation of radical transparency and it is employed in different ways in different contexts, and each has its own ethical implications.

The virtue of openness

In its broadest sense, transparency simply means openness, especially when it comes to revealing and sharing information. What makes it “radical” is when information that was previously closely guarded is systematically opened up to a wider audience, whether that’s within the organisation or without.

The primary ethical virtues of radical transparency are that it improves accountability and prevents corruption, in the sense of the improper use of power.

A culture of radical transparency not only makes it harder to conceal wrongdoing or compromising information, it also encourages a greater sense of honesty in dealings with others because of the anticipation that all information about those dealings will be revealed.

Radical transparency can also help counteract some of the power dynamics that influence decision making within organisations, whereby individuals might be reluctant to challenge the ideas and opinions of their leaders. A culture of radical transparency can improve decision making, as is claimed by Bridgewater, but also encourage people to speak up if they see something they believe is inappropriate.

Another form is wage transparency, which can promote fairness by giving employees more bargaining power in negotiations, placing them on a more even informational playing field with the employers. This is especially beneficial for those who are less inclined towards aggressive negotiation and can help counteract biases based on gender, racialisation and disability.

In an environment where trust in institutions, government and business is increasingly strained, radical transparency directed towards the public can serve to rebuild some of that trust. More organisations are laying bare information such as their employee diversity data, the results of internal or independent reviews – such as conducted by The Ethics Centre on behalf of the Australian Olympic Committee in 2017 – or details of their supply chains and environmental record.

Virtues and vices

Openness is a virtue. However, as Aristotle pointed out, any virtue taken to extreme can become a vice, and pushing transparency into “radical” territory steers it towards several ethical pitfalls and trade-offs that can easily be overlooked.

For a start, transparency sits in natural tension with privacy. Privacy is not just about restricting access to information but it can be thought of as the right of each individual to exercise some control over their personal information. This means they should have some power to choose whether or not to reveal their personal information. Some examples of radical transparency, such as wage transparency or the sharing of internal emails, can violate that right to privacy.

Privacy also enables us to protect ourselves from those who might use our personal information in bad faith to exclude, discriminate or persecute us. Radical transparency risks bleeding over into the personal space, such as if health, sexuality or religious attitudes are revealed that have no bearing on someone’s professional performance but which could expose them to unjust persecution.

One of the goals of radical transparency is to promote trust, but ironically it can also work to undermine it.

There are many kinds of special trusted relationships that are dependent on privacy, such as the relationship between patient and doctor or priest and parishioner. Should these conversations be made open, many people would end up concealing information for fear that it would be made public.

While no-one is suggesting radical transparency in the doctor’s surgery quite yet, it underscores that transparency in inappropriate contexts can actually cause people to suppress information rather than share it. There is already evidence that some workers in radically transparent workplaces change their behaviour to conceal information from their peers and act in a performative way that will be seen in a favourable light by others even if it’s not productive.

Trust in others is something that is learnt and must be cultivated through experience and practice. Should radical transparency seek to make trust redundant by making all information public, there is a risk that the virtue of trust will atrophy. This represents a real ethical risk should those individuals return to a less transparent environment where the virtue of trust is required once again.

Respectfully disagree

Radical transparency also requires an organisation to establish appropriate norms and culture in order to execute it in a safe and non-toxic way. In many instances, we modulate how we speak, how honest we are and what information we share on the basis of the relationships we have and the respect we owe to the other parties. In many contexts, deference, sensitivity or an ethic of care – or just the norms of good manners – trump candour, such as when we are speaking to a senior or vulnerable individual.

If we have implicit norms that promote deference to senior management, for example, or that encourage us to be sensitive towards a colleague who has just lost their job, these can come into conflict with the norms of radical transparency. There are accounts of employees feeling tremendous awkwardness when they’re thrust into radically transparent meetings where they’re expected to criticise managers or give reasons why a colleague should be fired.

It can take considerable time and effort to change the norms of discourse within the workplace to enable something like Dalio’s “meritocracy of ideas” in a way that is not overly confronting, where people feel like disagreement is tantamount to a personal attack.

These norms require that people feel respected, secure and safe to speak, which can also be threatened if radical transparency is executed poorly.

If implemented in a targeted and systemic way, radical transparency can deliver considerable ethical benefits in terms of elevating trust, improving decision making and encouraging constructive disagreement. But the most radical and hasty implementations carry serious ethical risks. Arguably, the point of the radical transparency movement is not to continually drive towards ever greater levels of transparency in every domain but to make openness an ethical norm that is, itself, no longer radical.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Althea Kuzman 2 MAY 2022

It’s just to get my foot in the door, I tell myself for the fifth time today as I offer my brain, my degrees and time to someone for free.

It’s a phrase that I’ve always found to be so incredibly visceral. I picture a door just about to slam shut in my face, that I have to hastily shove my foot in before it swings to a heavy close. Or a door that is slightly ajar, an unknown little me comes knocking and I have to slip my foot in and pry the thing open – to beg for an opportunity.

A foot in the door to do tasks which by now should be compensated. Because somehow in my years of trying to find a suitable job, no-one deems my skills to be transferable.

None of these scenarios really paint a picture for a healthy work foundation.

One would think that multiple arts degrees and years of casual jobs following instructions, would qualify me for an “entry level position”.

But it doesn’t. It leaves me cold emailing organisations, asking if they can send their off cuts to me so that I can get exposure. So that I can build a portfolio. So that I can earn a living and build my career.

But in my thinly veiled bitterness I digress. I chose the arts. I chose the creative field where getting your foot in the door is seen as a ‘privilege’. Having worked actual entry level jobs such as gallery host, our role was held up on a pedestal, yet we were not. We were made to simultaneously feel so lucky to have this job and yet so small and very replaceable. Why? Well, because it looks so good on the CV.

But in reality, it hasn’t really done anything to help my long-term career. And while I’ve had some wonderful bosses who have helped mentor me to learn and grow, this no longer seems like valid proof that I can, in fact, progress my career. It also doesn’t help that the pandemic cut arts positions in half.

The issue that lies here is often the refusal in hiring processes to acknowledge transferable skills. Which leaves you wondering, where do you gain these industry specific skills if no one will hire you for entry level jobs? Internships, of course.

Internship or Indenture?

Internships are fascinating mostly because of their prevalence, lack of regulation and lack of overall purpose. A report for the Fair Work Ombudsman by Adelaide Law School in 2013 states that “In Australia, as elsewhere, the term ‘internship’ is without fixed content. It has a broad and uncertain meaning covering everything from unpaid or paid entry level jobs to volunteer work in the not-for-profit sector”. This covers such a breadth of options that no wonder those starting out in their careers can fall into the trap of being exploited.

Internships are rife, particularly in the arts and on a global scale. Note when referring to the arts I include any creative industry, because they all bleed into each other – skills intersect and majority of skills learned are transferrable. There would be no issue with internships… if they were paid, but they rarely are.

In the UK, Sutton Trust is a non-for-profit organisation that fights for youth social mobility. Their work spans research on the prevalence and the social impact that internships have on recent graduates or those looking to change their career. Their 2018 report found that that 86% of arts internships are unpaid. The issue with unpaid internships is that life isn’t free.

Putting numbers on this, to live in London for a month whilst doing an unpaid internship costs £1,019 (about AUD$1800). And to make matters worse, due to the lack of legal clarity surrounding internships, there are concerns that some employers are exploiting this grey area. A harrowing ethical dilemma – getting an extra pair of hands without even attempting to understand their own responsibilities towards interns.

Due to the lack of legal clarity surrounding internships, there are concerns that some employers are exploiting this grey area.

It’s interesting to note that internships are always perceived as a stepping-stone. The Australian National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA) has a fact sheet on internships and what to expect, stating that they can be either paid or unpaid but the ‘crux of the situation is that it is an educational exchange’. NAVA go further to highlight the Fair Work Ombudsman’s criteria of an internship as a ‘meaningful learning experience, training or skill development’. This sounds completely reasonable, except when there is a precarious edge that tips easily into exploitation.

Researcher at the University of Montreal, Mirjam Gollmitzer recently detailed the precarious entryways into journalism. Often internships are seen as a socialisation into an industry or workplace, but Gollmitzer states that whilst that is ideal, research shows the opposite.

Through interviews with interns within the journalism industry, she finds interns who are ‘starved of mentorship and training’ and often left to their own devices. She highlights a powerful observation arguing that ‘the tacit assumption is that workers, not employers, are tasked with making the internship a success’.

How do we determine the success or value of an internship? To be seen as a meaningful learning experience, interns require mentorship, an environment to gain confidence and an understanding of how an industry works. Instead, Gollmitzer finds interns are often merely an extra pair of hands doing menial tasks, “with their experiences marred by haphazard interactions with time-strapped colleagues and arbitrary decisions by supervisors.”

The onus should be with employers to ensure interns are offered a valuable and structured experience where they can come out having truly learnt something and be given a genuine leg up in their career.

Instead many interns are left with a bitter taste in their mouth. They’re overworked, under paid (or not at all) and don’t walk away with skills or tangible experience they can take into an entry level job, which seems barely adequate. Which leads to the questions… when did jobs stop being a place of meaningful learning experiences and skill development? And how did we palm this off onto unpaid internships?

How did you get your start?

The above two questions are integral in understanding the shift that has occurred in the workplace. When listening to boomers talk about their start in the industry, often we hear those anecdotes about how they started in the photocopy room and someone noticed their intelligence and they were given a chance. Or how they were internally trained and given qualifications within the organisation.

The fact of the matter is that entering the workforce has been increasingly difficult for young people. The latest statistics from the HILDA Survey by The Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic & Social Research shows that only about 40% of graduates find full-time work in the first year out of full-time education. Their median hourly earnings are about two-thirds of median earnings of all workers, which is abysmal since our cost of living is ever on the rise. But this is certainly part of the discussion surrounding internships. With more and more people unable to find full-time work, we turn to casual work, to subsidise rent and to simply make a living, despite these casual jobs often not actually having relevance to one’s degree or career aspirations.

Casual work is the backbone of all unpaid internships. We all know someone who has worked in a pub whilst doing an unpaid internship in their desired creative field. But this leaves young people with burnout, and a distaste for a particular industry. Imagine that – already having doubts about something you studied just because from the get go you’re told you’re lucky to be working for free.

Nothing in life is free, therefore internships shouldn’t be. Making internships unpaid ‘learning’ experiences often leaves out entire demographics of people who simple cannot afford to work for free. It perpetuates the elite nature of industry, and the idea of the grind straight off the diving block. It’s cruel and unnecessary. Particularly because it wasn’t quite as brutal in different generations. For the first time ever, gen Z are running the risk of earning LESS than their parents, something that has never happened in the course of history.

How do we fix this? While I’m not well versed in economics or capitalism, I do know that people need to be paid for their work. Don’t take on an employee if you don’t have the bandwidth to mentor or financially compensate them. We need to start treating entry level jobs as a first stepping stone into an industry and leave the exploitation of young workers in the past, where it belongs.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we can’t learn from our past (and shouldn’t try to)

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

BY Althea Kuzman

Althea Kuzman is an emerging curator and arts writer. She holds a Master of Curating and a BA in Communications and International Studies.

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 21 APR 2022

There’s a reason our parents told us to steer clear of discussing politics (along with sex and religion) in polite company. Because as soon as politics is raised, there’s a very real chance that the company will become significantly less polite.

One reason political disagreements can be so divisive is that, unlike other contentious topics, like whether pineapple belongs on pizza, politics taps into our deeply held moral values and emotions: taxation policy isn’t just about the budget’s bottom line, it’s fundamentally about fairness; climate policy isn’t just about decarbonisation, it’s about the harm that our society is inflicting on future generations.

The moral dimension of politics can make us less tolerant of disagreement and more likely to see other views as not just different but mistaken, and perhaps dangerously so. It’s easier to shrug off someone’s opinion about the latest episode of The Bachelor than it is to let their views on asylum seekers pass without rebuttal.

The good news is that there are ways to have fruitful conversations about political differences if you approach them with care.

Before you start

Disagreements don’t have to be corrosive to our relationships or wellbeing. In fact, genuine disagreements give us an opportunity to learn, grow and share our perspectives with others. But they take time and effort to set up.

So before you utter a contrary opinion to a friend or family member about a political issue, first reflect on the strength of your own views and how open you are to new perspectives and evidence.

In today’s heated political environment there can be a great deal of pressure on us to form an opinion and take a side before we’ve had a chance to digest all the relevant information. There’s also a strong tribal element to politics that makes us more likely to adopt the views of ‘our side’ and oppose anything said by the ‘other side’. Many of us might even admit we hold opinions that we would struggle to justify if pressed.

Ideally, the strength of our convictions should be proportional to the strength of the reasons and evidence we can muster in their support. It’s still OK to form an opinion without doing a Masters degree on it first, but it does mean we should remain open to new information and perspectives that could change our mind. As a rule of thumb, if there are no reasons or evidence that could even hypothetically change your mind, then you’re being dogmatic and will likely receive no joy arguing about your views with others.

Before deciding to engage in a political disagreement, it’s also worth pausing to consider whether it’s worth arguing at all. It’s natural to feel compelled to correct a view you believe is harmful or wrong. But if it is likely that a disagreement could get heated or emotional, or it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to influence the other person at all, then getting into a debate might end up being entirely fruitless. All you might achieve is damaging the relationship, even if you’re in the right.

Sometimes relationships matter more than being right. If you’re arguing with someone close to you, someone you care for or depend on, it may not be worth eroding that relationship for the sake of a political argument, especially if it’s almost certain to go nowhere.

And if you do want to actually change someone’s mind, you need to establish a base of trust and respect first. Foregoing one heated conversation in order to strengthen a relationship means you can build enough trust and respect so that you can have a constructive disagreement sometime in the future. Once you’re sure they’re willing to listen to you, you might even have a shot at changing their mind.

Where to start

If you do decide to wade in, the very first thing to do is keep your mouth shut! At least at the start of the conversation.

When we hear someone say something we disagree with, our first impulse is often to express our own contrary opinion. The problem is that this immediately frames the conversation as a ‘war of ideas,’ which can trigger all the baggage this metaphor implies. We see our conversation partner as our ‘opponent,’ we become focused on ‘winning,’ on ‘undermining’ and ‘outflanking’ their position. And absurdly, if we do learn something and change our mind, that’s considered ‘losing’.

It’s better to frame the conversation in terms of fellow travellers exploring an issue together. You might have different perspectives, but you have the same ultimate goal: improving your understanding of the world.

In order to avoid slipping into the argument-as-war frame, instead of expressing your opinion up front, start by asking questions. Ask why your conversation partner believes what they do. Get them to elaborate on what they mean by various terms. Then listen carefully, paying special attention to both the content of what they say as well as their emotional state when saying it.

Once they’ve had a chance to express themselves uninterrupted, summarise their view back to them and validate how they feel. You can do this without necessarily validating the content of their beliefs, even if you disagree with them. You might say something like “I see you’re really concerned about the economic impact of climate policy”, which acknowledges how they feel but doesn’t commit you to agreeing or disagreeing with them.

This kind of reflective listening achieves two crucial things. First, it gives you a fighting chance of actually understanding their view in detail rather than assuming you know what it is. This is important because people often mean different things when they use terms like ‘freedom’ in a political context, which can lead to confusion and crossed wires unless you probe them on what they mean.

Secondly, reflective listening helps people feel heard, which signals respect and can lower the temperature of a conversation. In fact, a lot of defensiveness can simply be a result of people wanting to be heard and feeling like no-one is listening.

Common ground

If you want to progress the conversation, the next stage is to seek out common ground, especially around values or goals that you both agree upon. For example, you might both care about taxes not being wasted, or you both care about the wellbeing of the next generation. At this point you can start to frame your difference in perspective as being different strategies to achieve common goals. This can take a lot of the edge out of arguments, making them feel less like you’re fundamentally at odds and show that you’re only disagreeing about the means to achieving shared ends.

Crucially, if you ever feel the conversation getting heated to the point where it’s difficult for either of you to engage constructively, then it can be wise to back out and change the subject before it’s too late. You can always revisit the topic once things have cooled down.

It’s also important to not let the conversation drag out. It’s unlikely that you’ll be able to fully grasp someone’s views or change their mind in a single conversation. But even a short conversation can help you better understand their views and allow you to offer up a different perspective. And if it’s done with patience and respect, it can open the door to future constructive conversations. After a few such chats, you might even find you change their mind – or find that your own view has changed. That’s not a bad thing.

The highly charged moral dimension to politics is why conversations about it are so fraught. But if we engage thoughtfully and respectfully we can have a rich conversation about politics, and still have a fighting chance of making it to dessert with friendships and family relationships intact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Tyson Yunkaporta is a researcher, arts critic, poet, and traditional wood carver. He works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges and is the founder of the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab at Deakin University.

A scholar of free-ranging ideas

Yunkaporta is not your typical academic. In a recent interview, he said:

“I try to avoid naming anything. And I try to avoid making too much sense, and I try to say things a bit differently every time and to mix it up. And I’ll make points that you can’t put together. I do that quite deliberately because I don’t want the things I’m thinking or working on to become an ideology or a brand, or something that people can use as a name… you’ve got to avoid that packaging and repackaging of ideas and let these things be free-range.”

Yunkaporta tries to keep his writing and discussions “free-range” because he doesn’t want to give complex ideas or concepts an “artificial simplicity.”

According to Yunkaporta, when we simplify complex ideas, they can become easily distorted or manipulated and the original intention behind them can become lost. But more problematically, when we simplify complex ideas, we fail to see how they connect to the larger patterns of creation at work.

“There is a pattern to the universe and everything in it.”

Nothing is really created or destroyed, it merely moves and changes. When we start to pay attention to the way that things move and change, and take note of the patterns that they make, we gain a better understanding of the world around us.

This is important, Yunkaporta states, because “future survival of all life on this planet will be dependent on humans being able to perceive and be the custodians of the patterns of creation again.”

Indigenous thinking can save the world

Yunkaporta’s recent book Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, is all about identifying and learning from the patterns of creation.

Sand Talk has sometimes been described as an exercise in “reverse-anthropology”, because rather than looking at Indigenous knowledge systems and practices from a Western perspective, Yunkaporta examines Western knowledge systems and practices from an Indigenous perspective.

He is careful about what knowledge he shares in the process, explaining that symbolic knowledge is often restricted (for example, by age or birth order) or is only appropriate for a specific places or groups (for example, members of particular clans).

However, he shares enough to help his readers start to recognise patterns in the world around them and to “come into Aboriginal ways of thinking and knowing, as a framework for the understandings needed in the co-creation of sustainable systems.”

Although Yunkaporta believes that sustainable systems cannot be manufactured by individuals (this is something that we must undertake collectively), he does think that each of us plays an important role as an agent of sustainability.

Agents of sustainability have four main protocols or guidelines, according to Yunkaporta: diversify, connect, interact, and adapt.

These guidelines tell us that we should diversify our interactions, so that we engage with people and systems that are dissimilar to ourselves and what we’re used to.

We should also aim to expand the networks of people that we currently engage with, so that we connect with as many new people and engage with as many new systems as we can.

Through these connections, we should also share knowledge, energy, and resources. But most importantly, we should allow ourselves to be transformed by the knowledge, energy and resources that are shared with us.

Ironically, Yunkaporta believes that frameworks are nothing more than “window dressing.” Yet, as he himself highlights, the four main protocols for sustainability agents are a kind of framework for sustainability.

This contradiction is, however, just part of Yunkaporta’s style. He describes his work as a “free-range ramble that should never be taken at face value.”

He writes to provoke thought and reflection in his audience, not to give them all the answers. After all, he muses, “perhaps the worst possible outcome of this work would be civilisation embracing these ideas.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jeremy Bentham

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Luara Ferracioli Dr Sam Shpall 12 APR 2022

Senior Lecturers in Philosophy at the University of Sydney, Dr Luara Ferracioli and Dr Sam Shpall, participated in a live Ethics Centre conversation last year, discussing: how do we respectfully disagree? Ferracioli and Shpall concluded the following seven lessons, and how there can be value in disagreeing.

It often feels like we’ve lost a sense of principled disagreement – the idea that it’s OK if reasonable people think differently about something that matters.

In part, this is because we’ve changed the boundaries on what it’s OK to disagree about. Today, disagreement and debate about sensitive issues is seen by some as harmful or violent.

This can be interpreted as both attempts to de-platform bigoted ideologies, and also as those upholding the status quo having their power threatened and hiding behind a veil of civil society. It’s why subjects like Black Lives Matter and Critical Race Theory attract so much opprobrium – they speak directly to and challenge power, particularly latent and overt power dynamics.

We can all be guilty of treating disagreement as something that must have a winner and a loser. Whilst in other times disagreement has been used as a tool for everyone to learn; today, we disagree without any readiness to be persuaded.

When should we respectfully disagree? Should we always be open to having our mind changed? Can we remain friends with someone who we disagree with about things that really matter?

1. Genuine disagreement is not a bad thing.

There is value in good disagreement. Arguing well helps to flesh out all sides of an issue, bring to light underrepresented perspectives and contribute to solutions that benefit the most people; as in a true, functioning democracy and political system.

People occasionally conflate disagreement over an idea with a personal attack. This is a mistake, because disagreeing over issues and rationally debating the outcome – whether it’s who will do the dishes or how to allocate the national budget – is the best way to ensure a measured outcome that is in the best interests of the greatest majority. The more diversity of opinion there is in the discussion, the better the chance that the outcome will be balanced and representative of the greatest range of points of view.

The trouble lies in ensuring that the debate is measured, rational and charitable, and does not resort to humiliation and point scoring, as it often does in politics and personal disagreements. It’s important, also, to consider whether some disagreements of opinion are so fundamental that they license strong non-engagement moves like cancellation, de-platforming, and defriending; for example, boycotting a festival because of the presence on the bill of an act or speaker with whose ideas you disagree, or demanding their invitation to speak be withdrawn, such as in the recent case of Sydney Festival.

2. Genuine disagreement is often positively necessary for intellectual and emotional development.

Hopefully it’s already clear that cancelling and de-platforming people’s voices is not the way to stimulate a healthy culture of disagreement. Imagine I disagree with my partner about the wisdom of buying an apartment. One of us could simply acquiesce to make things more comfortable. This seems dangerous and unproductive. It makes it more likely that we will make the wrong decision, and it makes it more likely that at least one of us will feel ignored, disrespected and resentful. Notice how familiar the gendered dynamic is here in heterosexual romantic relationships: the controlling, all too often abusive man makes the decisions and expects or enforces compliance.

To make the right decision we both need to express our needs, wants and arguments clearly, and treat each other’s opinions with respect, working our way through the pros and cons to eventually reach a compromise based on mutual respect, not on one person overpowering the other.

In the case of the marriage equality debate in Australia, it came down to a national referendum, where the majority voted in favour of same sex marriage, proving pointless all the misleading ad campaigns and snarky media baiting of politicians and pundits.

3. Sometimes what people call “disagreement” is not disagreement at all.

Rather than disagreeing over philosophical ideas, sometimes people resort to the tactics of personal attack and outright hostility. If your aim is to humiliate a political opponent or win an election, you might well find that genuine disagreement and a contest of ideas is a less effective strategy than belittling them and misrepresenting their policies. (This goes partway to explaining political apathy, because it appears that many politicians are more interested in humiliating their opponent and scoring a point than having a real battle of ideas.)

Similarly, if your aim is to “win” a fight with your partner (and make yourself feel good, humiliate them, and put them in their place), you might find that genuine disagreement is a less effective strategy than personal attack. How often in a personal disagreement have you found yourself wanting to bring up a time in the past when the person has wronged you, that has no bearing on the current situation?

These analogies run quite deep, involving posturing, self-absorption, strong rhetoric, a lack of charity, no engagement with the “opponent’s” perspective, and so on. It’s not a true “disagreement” and contest of ideas, though, but a personal attack motivated by ego.

4. Sometimes what people call “offensive” and “hostile” is in fact disagreement.

In any interlocution, the first interaction always sets the tone: if it starts off hostile, that hostility will only escalate. You need to ask yourself: are you attempting a good faith engagement, or are you being defensive and stereotyping and categorising your opponent’s argument points?

Take, for example, the disagreement in the media and social media between podcaster Joe Rogan and musician Neil Young. Young removed his music from streaming service Spotify to protest its hosting of Rogan’s podcast, accusing The Joe Rogan Experience of spreading misleading information about Covid-19 vaccines.

Young followed up with a plea for Spotify employees to leave the company before it “eats up [their] souls”. Other prominent social media users then posted clips of Rogan using racial slurs. Rogan apologised for the slurs and said he will try, “in the future, to balance things out” with information on Covid. Spotify CEO Daniel Ek wrote, “based on the feedback over the last several weeks, it’s become clear to me that we have an obligation to do more to provide balance.”

5. Contemporary technologies (text messaging, emailing, social media) can make it harder to disagree well.

Communicating through the brevity of screens does not do much to help the art of good disagreement. With social media we’re getting less charitable with our opponents’ points of view and not always assuming the best version of their views. The way social media enables discussion is counter-productive – it’s so short, often anonymous, and you’re not looking at each other so you can’t see that your opponent is generally trying to have a good faith discussion.

Sarcasm and irony do not translate over text – consider how many times you’ve been misunderstood over email or text message. Abbreviating our vocabulary down into the bite size shapes of an emoji also engenders a poverty of language and ideas that benefits nobody. Consider Godwin’s law, that the longer an online discussion grows, the more the probability of a reference to the Nazis or Adolf Hitler reduces to zero.

6. Philosophical-collegial disagreement is a useful model for productive transformations of disagreement, from the personal to the political.

The philosophical model of disagreement has some valuable tools that should be exported for use in everything from intimate relationships, work environments and political culture to anonymous social interaction. One of the hallmarks of bad disagreement is a lack of charity – presenting your interlocutor in an unflattering light.

One of the things philosophers try to do at a university level is to reconstruct the best, most plausible, compelling version of the argument that one’s opponent is presenting. The principle of charity is related to a lot of other principles of agreeing well, such as the principle of intellectual humility, understanding that even one’s most cherished beliefs could be improved or better justified.

You want to win not because you put your opponent down but because you’ve made the best argument and your opponent can see why it should go your way.

7. Some disagreements are not worth having

The phrase ‘agree to disagree’ is a funny one that’s worth thinking about – it’s usually employed in the same way as phrases such as ‘it’s all subjective anyway’ or ‘everyone has their opinion’, not as a real move in a conversation but more as an ending to the conversation. Sometimes we need to end a conversation because it’s not getting anywhere, but sometimes we employ phrases like that to paper over the fact that we don’t have anything more to add to our argument.

But what about when one party to a disagreement rejects the foundational presuppositions of liberalism? For example, if someone thinks that men and women are fundamentally different and women deserve to be paid less than men, it might be very difficult to have a reasonable conversation with them when your foundational viewpoints are so radically different.

We have laws that prohibit certain forms of hate speech, of course, but these are hard to enforce and do not really help to answer many of the practical questions about how to interact with people who have these views.

We can’t give an overall theory about what to do in such cases, but we want to suggest that we steer clear of two dangers:

- failing to confront the genuinely inegalitarian, illiberal views; pretending that such views deserve the same sorts of consideration as liberal ones;

- and overstretching this response to illiberal exceptions.

Maybe you disagree with us about some of the things we’ve written, but hopefully you agree that there is value in disagreeing well.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Normativity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

BY Dr Luara Ferracioli

Luara Ferracioli is Associate Professor in Political Philosophy at the University of Sydney and ARC DECRA fellow. She was awarded her PhD from the Australian National University in 2013, and has held appointments at the University of Oxford, Princeton University, and the University of Amsterdam. Her first book Liberal Self-Determination in a World of Migration was published in 2022 with Oxford University Press, and her new book Parenting and the Goods of Childhood is forthcoming (with Oxford University Press).

BY Dr Sam Shpall

Dr Sam Shpall is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Philosophy at The University of Sydney. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Southern California in 2011, and was a Postdoctoral Fellow there from 2011-2013. From 2013-2015 he was the Postdoctoral Associate in Law and Philosophy at Yale University, and a Lecturer at the Yale Law School. He also taught philosophy in four New York State Correctional Facilities from 2014-2015 as a faculty member of the Bard Prison Initiative. He works mostly in ethics, moral psychology, and the philosophy of art.

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Often, when we try to understand something, we ask questions like “What is it for?”. Knowing something’s purpose or end-goal is commonly seen as integral to comprehending or constructing it. This is the practice or viewpoint of teleology.

Teleology comes from two Greek words: telos, meaning “end, purpose or goal”, and logos, meaning “explanation or reason”.

From this, we get teleology: an explanation of something that refers to its end, purpose or goal.

For example, take a kitchen knife. We might ask why a knife takes the form and features that it does. If we referred to the past – to the process of its making, for example – that would be a causal (etiological) explanation. But a teleological explanation would be something that refers to its end, like: “Its purpose is to cut”. Someone might then ask: “But what makes a good knife?”, and the answer would be: “A good knife is a knife that cuts well.” It’s this guiding principle – knowing and focusing on the purpose – that allows knife-makers to make confident decisions in the smithing process and know that their knife is good, even if it’s never used.

What once was an acorn…

In Western philosophy, teleology originated in the writings and ideas of Plato and then Aristotle. For the Ancient Greeks, telos was a bit more grounded in the inherent nature of things compared to the man-made example of a knife.

For example, a seed’s telos is to grow into an adult plant. An acorn’s telos is to grow into an oak tree. A chair’s telos is to be sat on. For Aristotle, a telos didn’t necessarily need to involve any deliberation, intention or intelligence.

However, this is where teleological explanations have caused issue.

Teleological explanations are sometimes used in evolutionary biology as a kind of shorthand, much to the dismay of many scientists. This is because the teleological phrasing of biological traits can falsely present the facts as supporting some kind of intelligent design.

For example, take the long neck of giraffes. A shorthand teleological explanation of this trait might be that “evolution gave giraffes long necks for the purpose of reaching less competitive food sources”. However, this explanation wrongly implies some kind of forward-looking purpose for evolved traits, or that there is some kind of intention baked into evolution.

Instead, evolutionary biology suggests that giraffes with short necks were less likely to survive, leaving the longer-necked giraffes to breed and pass on their long-neck genes, eventually increasing the average length of their necks.

Notice how the accurate explanation doesn’t refer to any purpose or goal. This kind of description is needed when talking about things like nature or people (at least, if you don’t believe in gods), though teleological explanations can still be useful elsewhere.

Ethics and decision-making

Teleology is more helpful and impactful in ethics, or decision-making in general.

Aristotle was a big proponent of human teleology, seen in the concept of eudaimonia (flourishing). He believed that human flourishing was the goal or purpose of each person, and that we could all strive towards this “life well-lived” by living in moderation, according to various virtues.

Teleology is also often compared or confused with consequentialism, but they are not the same. If you were to take a business that specialises in home security, for example, a consequentialist would tell you to look at the consequences of your service to see if it is effective and good. Sometimes, though, it will be hard to tell if the outcome (e.g., fewer break-ins or attempted break-ins) can be attributed to your business and not other factors, like changes in laws, policing, homelessness, etc., or you might not yet have any outcomes to analyse.

Instead, teleological approaches to business decision-making would have you focus on the purpose of your service i.e., to prevent home intrusion and ensure security. With that in mind, you could construct your services to meet these goals in a variety of ways, keeping this purpose in mind when making hiring decisions, planning redundancies, etc., and be confident that your service would fulfil its purpose well (even if it is never needed!).

But how do we decide what a good purpose is?

Simply using a teleological lens doesn’t make us ethical. If we’re trying to be ethical, we want to make sure that our purpose itself is good. One option to do this is to find a purpose that is intrinsically good – things like justice, security, health and happiness, rather than things that are a means to an end, like profit or personal gain.

This viewpoint needn’t only apply to business. In trying to be better, more ethical people, we can employ these same teleological views and principles to inform our own decisions and actions. Rather than thinking about the consequences of our actions, we can instead think about what purpose we’re trying to achieve, and then form our decisions based on whether they align with that purpose.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

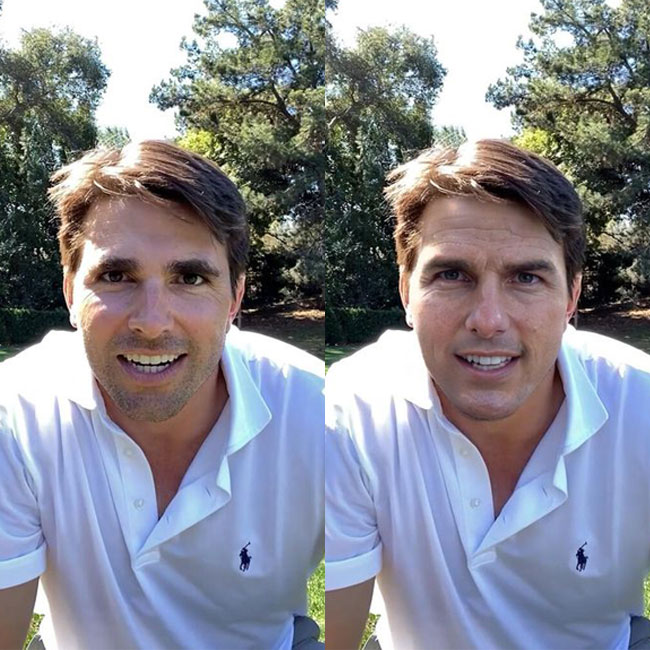

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

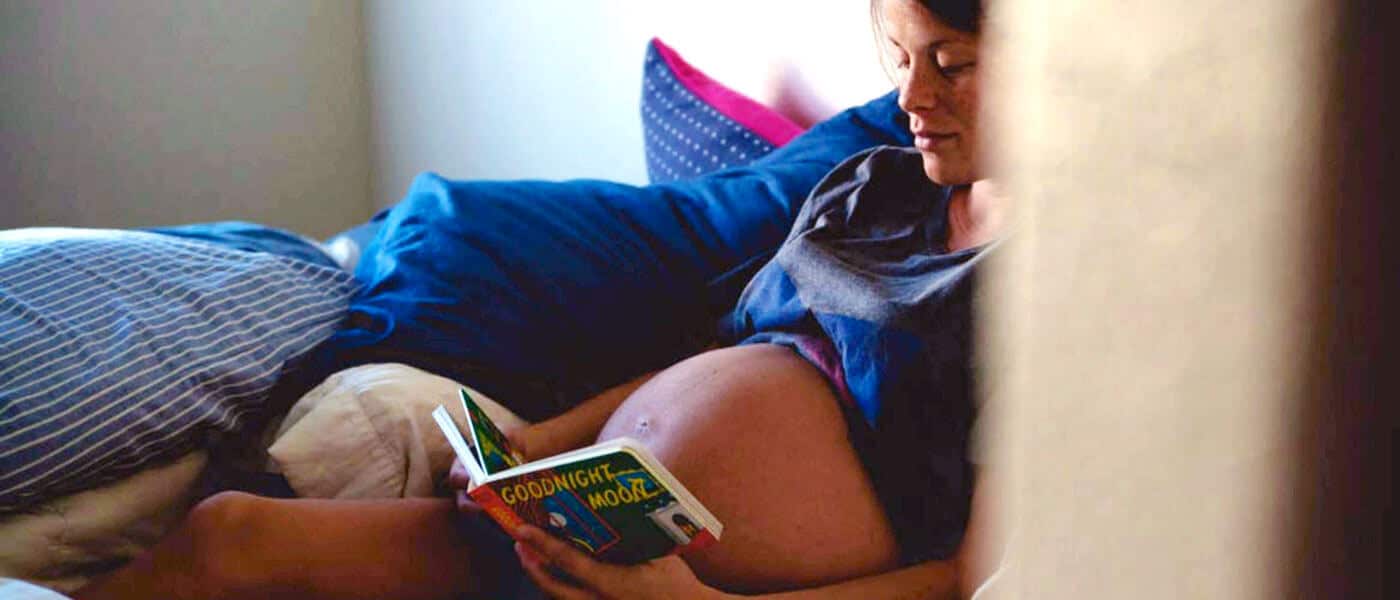

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Lucy Peach 1 APR 2022

Most people probably know more about the cycle on a washing machine than the one that got us all here. I’m talking about the menstrual cycle (again).

It’s true that we’ve made major gains in shedding some of the menstrual stigma in recent years but there is still a lack of awareness and interest in the cyclical lives of 26% of all people on Earth. There are real consequences to this.

For a start, menstrual education is still reduced to two things: the management of a period and how to control our capacity to reproduce. No one explained that the hormones of the menstrual cycle weren’t just for making babies and that my cycle hormones shape who and how I am. I didn’t know, that far from being an unpredictable rollercoaster (that I would internalise as constant feelings of being too much or not enough), that there was a pattern to the emotional landscape of my month, that there were predictable phases to the cycle that could be harnessed. That it was ok to feel differently from week to week.

At a tender age, I learnt that my body was a problem to be fixed, with pads, tampons and soon enough with the pill. I believed I was safest while my cycle was disarmed. Until I was ready for a baby, what was the point in having one at all or so I thought? The truth is, without ovulation, we have no hormones and therefore no cycle at all. I wonder, would I have been so eager to reject ovulation in favor of the pill during my teens and twenties had I known of this?

I didn’t know that there were short and long-term protective health benefits to ovulation that taking the pill would eliminate. I didn’t know it was common to feel depressed and flat while taking it. I felt crazy. Instead of cultivating care and curiosity for my young body and what it could do, I leant not to trust it.

This disregard for menstrual cycles extended to the scientific community such that until the 90’s, clinical trials for new drugs weren’t required to include women at all.

Because menstrual cycles were seen as too complicated, men were considered the biological norm.

It seems that even amid a growing movement of awareness and appreciation for menstrual cycles, this default male setting still persists.

When thousands and thousands of women and menstruators reported changes to their cycle after taking the Covid vaccine, their concerns were initially dismissed by the medical fraternity. Women were waved away and stress was cited as the probable culprit for the mostly temporary changes.

It is true that stress can wreak havoc on a cycle — and who hasn’t felt stressed in new ways since the arrival of the pandemic? But the real kicker, was that there was no proof to speak of; important early clinical trials investigating the side effects of the Covid vaccine failed to consider the impacts on women’s menstrual cycles. This glaring omission at such a critical juncture is menstrual stigma still in action. That women were dismissed before being asked about their experiences after the vaccine is an indictment into how far we haven’t come.

Women were dismissed before being asked about their experiences after the vaccine is an indictment into how far we haven’t come.

In the absence of due diligence, people worried and concerns for post vaccination fertility also proliferated, risking confidence in the vaccine unnecessarily.

Vaccines work by creating an immune response which can cause the body stress. It stands to reason that there might be side effects to our cycles when our immune system is triggered. The latest research was funded by the NIH and published in Obstetrics and Gynecology. It was confirmed that while changes were (on average) minor and temporary, it was true: there was an impact. After looking at three cycles before and after vaccination, on average, the impact on cycle length following vaccination was just under a day.

For people who had both shots within one cycle, the average cycle length extension was 2 days and of these people, there were 10% who experienced cycle delays of 8 days or more. All of these changes were reported to have been resolved within two subsequent cycles and there was no effect found on the length of the bleed itself. Obviously within all of the experiences that create averages, the range for individuals could be considerable but with variations of up to 8 days considered to be within the realm of a normal cycle, these results are generally reassuring. Furthermore, in another study with more than 2000 couples there was no difference found in fertility when comparing unvaccinated and vaccinated couples. Conversely, a Covid infection was associated with a temporary decline in male fertility. So far so good.

Research like this is a positive step after a bungled start and authors of the menstrual study have called for more investigation into how the Covid-19 vaccination could affect other aspects of menstruation such as pain and changes to the bleeding itself. Going forward, bigger sample sizes that also include menstruators with more varied experiences are important.

With access to information and the stains of stigma beginning to fade, women and menstruators are learning to listen to their bodies and to speak up about their experiences. To be wary of doctors who prescribe the pill to fix a period when it merely masks underlying issues. To demand better than the average wait time of eight years to receive an endometriosis diagnosis and subsequent treatments. Weary of being disregarded when it comes to our health, we are finally beginning to trust ourselves. As Lisa Hendrickson-Jack explains in ‘The Fifth Vital Sign’, the menstrual cycle gives us important insights and is a critical marker of our overall health, just like heart rate or body temperature. Understanding your menstrual cycle is basic body literacy that is crucial to wellness.

The changes to menstrual cycles may be no more significant than a sore arm, but that doesn’t mean we don’t deserve to know about them. Small changes can still be significant to people hoping to plan or avoid a pregnancy, for instance. We need vaccines to combat Covid but we also need to be informed.

If there are any silver linings to be had during Covid it’s that we know that the old ‘normal’ wasn’t working for many of us.

Women’s health has long been overlooked, under-researched and under reported and now perhaps the new normal is to consider women’s health from the outset.

Hopefully it will be for the future we are carrying.

Normalise asking people about their cycles whether you are a researcher, a doctor, a partner or even a friend. Normalise noticing your own cycle and how you feel throughout the month. Normalise expecting better.

Lucy Peach, day 28 and vaccinated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

BY Lucy Peach

Lucy Peach is a long-time champion of the power of the menstrual cycle and an advocate for self-love and positive body literacy. She’s educated and empowered thousands with her theatre performances, workshops, and book, using science stories and songs to shift the period narrative in our culture from one of shame to one of pride. Lucy has spent the past two decades studying human biology, woman’s health & wellbeing, and Menstruality Leadership. She has a Bachelor of Science in human biology and biomedicine with honours in medicine, and a graduate diploma of education in human biology.

The Dark Side of Honour

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 30 MAR 2022

If someone insulted a family member, would you rush to defend their honour? If you said “yes”, then you’re not alone. In fact, American actor Will Smith did just this when he confronted comedian Chris Rock on stage at the 94th Academy Awards in March 2022.

It happened after Rock directed a joke at Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett-Smith, that appeared to make light of her alopecia, a medical condition that causes hair loss. Smith mounted the stage, strode up to Rock and slapped him across the face, before returning to his seat shouting “Keep my wife’s name out of your fucking mouth!”

Many onlookers in the room and around the world were shocked at this outburst of violence, even if they thought the joke was offensive and hurtful to Pinkett-Smith. But others interpreted things differently. They saw a chivalrous husband doing what a good husband should do.

One such defence of Smith came from American comedian and actress, Tiffany Haddish. “As a woman, who has been unprotected, for someone to say, ‘Keep my wife’s name out your mouth, leave my wife alone,’ that’s what your husband is supposed to do, right? Protect you”, she told the media during the awards.

“That meant the world to me. And maybe the world might not like how it went down, but for me, it was the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen because it made me believe that there are still men out there that love and care about their women, their wives.”

Haddish is speaking about the importance of an old moral concept: honour. It’s one that has been a core feature of many cultures around the world and throughout history, and even where its influence has waned, it still exerts some pull on our hearts, as we can see in the case of Will Smith.

But honour also has a dark side, not least contributing to violence as well as the oppression of women. The question is whether honour ought to play a role in our ethical thinking today, or whether it should be replaced by a more liberal ethic that prioritises reducing harm and injustice.

Reputation is life

At its heart, honour is about protecting one’s reputation as a virtuous and trustworthy individual. Anything that threatens that reputation, whether scurrilous gossip or a verbal insult, can – or even must – be forcefully challenged, violently if necessary.

Honour is particularly prevalent in smaller-scale societies that lack trustworthy institutions that prevent people from lying or cheating others, like law courts or government regulation of business. In smaller societies, it’s often left to individuals to figure out who can be trusted and who should be avoided.

This is where reputation plays a key role. If you have a good reputation, others will be happy to cooperate with you. If you’re found to be an untrustworthy cheat, word will get around that you should be avoided. In a society where cooperation might be essential to your survival, a bad reputation could be tantamount to a death sentence.

This is one reason why insults trigger such an acute response to people who value honour. An insult does two things: first it besmirches the target’s good name, often accusing them of some deviant or dishonourable act; and second it paints them as being weak, which is seen as a kind of moral vice in itself, especially in honour cultures that have norms that equate masculinity with strength.

As the psychologists Richard Nisbett and Dov Cohen describe in their famous study of the honour culture in the Southern United States:

“A key aspect of the culture of honor is the importance placed on the insult and the necessity to respond to it. An insult implies that the target is weak enough to be bullied. Since a reputation for strength is of the essence in the culture of honor, the individual who insults someone must be forced to retract; if the instigator refuses, he must be punished – with violence or even death.”

Even when honour culture has waned in popularity, as it has in the Southern United States, it can continue to influence the way people behave. Nisbett and Cohen describe one experiment that showed that when university students from Southern states were insulted, they were more likely to show signs of elevated hormones related to stress and aggression than students from the Northeastern states.

The price of honour

If an insult is to be met with force rather than shrugged off, then it can easily descend into conflict even over trivial statements. It can also easily lead to violence. Nisbett and Cohen cite evidence that the homicide rate in the Southern United States is significantly higher than other regions.

But there’s another price of honour: the oppression of women. Honour cultures are usually also patriarchal, with men occupying most of the positions of power. In these societies, men often seek to control women, especially their sexuality.

One motivation is to help ensure the paternity of their children, which is difficult without modern medical technology. One way to do so is to only marry a woman who is virgin and then to control her sexuality to guarantee sexual exclusivity. This is one reason why many honour cultures are obsessed with sexual fidelity, primarily of women, and why promiscuous women can be subject to “honour killings” by their own families.

This connects with another motivation for men to control women’s sexuality: alliances. Marriage has been used as a strategic tool for millennia to create bonds between families, usually to serve the interests of the heads of those families, who were predominantly men.

Again, virginity and sexual fidelity make marriable women more attractive as mates for other men, which feeds into an honour culture that seeks to protect the reputation of women as being faithful and chaste. These same cultures often encourage men to violently respond to any perceived slight against their female family members, or to ostracise or enact violence towards women who choose to deviate from the sexually oppressive norms constraining them.

The decline of honour

None of this is to suggest that Will Smith was seeking to control women as a sexual or political resource. But the same sensitivity to honour that motivated him to stand in his wife’s defence can be used to control and disempower women. Indeed, some interpreted Smith’s slap as robbing Pinkett-Smith of her own voice when it came to defending herself.

While honour can be a vehicle to encourage people to take responsibility for their actions, to promote virtues like honesty and loyalty, it can also place a higher priority on protecting one’s reputation – and that of their family (and often the women in their family) – over de-escalating violence and solving injustices through other means.

Honour is also largely redundant in a world with institutions that protect us from miscreants. We no longer live or die by our reputation. This is why we teach children the “sticks and stones” rhyme. Yet it is all too easy in the heat of the moment to let a sensitivity to our reputation carry us away, compromising the values of care and justice that have become dominant in liberal societies.

It is precisely these values that are reflected in Will Smith’s public apology, posted the day after the Academy Awards when some of the heat had died down. “Violence in all of its forms is poisonous and destructive,” he wrote in an Instagram post. “There is no place for violence in a world of love and kindness.”

The question for each of us to answer next time someone insults us or a loved one is what do we value more: a society of reactive violence or a society where we prioritise compassion and justice through more considered responses?

Image: Ana Gremard / Flickr

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY John Neil 28 MAR 2022

Ash Barty’s shock retirement from tennis while seemingly at the peak of her powers left the sporting world reeling.

But from all accounts it was no surprise to those close to her. From what we’ve learnt about her throughout her career, and especially through her retirement announcement, the lack of surprise from those close to her is a testament to Barty’s principles of leadership.

In times of uncertainty and unpredictability we often look to our folk heroes to provide guidance and inspiration. However, all too often we default to sportspeople as the exemplars for lessons in how to live, cherry picking attributes of heroism and resilience on the field of play only to find our heroes’ winning lustre tarnished when the invariable accounts of various misdeeds or behaviours kept private between teammates invariably surface.

Exemplary people play a key role in the branch of ethics known as virtue ethics. Its head coach, Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, gave exemplars a starting guernsey in his philosophical line up because they are people who can practically demonstrate to others how to live a life well. For Aristotle, ethics is not simply a matter of internalising a rule; but is about doing the right thing at the right time, in the right way and for the right reason. Moral exemplars help show us the way.

Both on and off the court, Ash Barty is a moral exemplar in the full sense of Aristotle’s term. In her humility, good will and clear-eyed purpose that she demonstrated in her retirement announcement, we can see five fundamental principles for how to lead in our work, and how to live a life inspired by someone worth emulating.

1. Relationships are an ends, not merely a means

Throughout her career Barty was consistently clear how highly she valued relationships; not because they helped her achieve sporting success, but because they were important in and for themselves. They were a foundation for her to live a flourishing life, on and off the court.

Her opening exchange in her interview announcing her retirement with good friend Casey Dellacqua, spoke volumes for the power of relationships and friendships in particular. The refreshingly genuine and heartfelt connection that began the exchange with her good friend, who thanked Barty for ‘trusting me again’ to break the news was as refreshing as it was surprising. Less surprising when we remember that Barty, in a sport notorious for its individualism, referred continuously throughout her career and especially in winning, to the central role of her team, family, friends and community played in it – just as she did in her retirement announcement.

As all great leaders do, Barty skilfully and genuinely removed herself from the centre wherever possible – no mean feat in an individualistic sport like tennis. Relationships for Barty, as they are for the best leaders, are of intrinsic value in themselves. They are not a means to achieve an outcome, they are an end in themselves.

And no doubt just as they helped Barty get the best out of herself, she, in turn, enabled the best in the team around her.

2. Leave it all out there – but don’t lose yourself in the process

On the surface Barty lived the cliched sporting principle ‘leave it all out on the field.’ From her epic Wimbledon title win after coming back early from a serious hip injury to reach the final and then holding off Karolina Pliskovain in a four-set thriller through to her epic Australian Open win – which is now all the more astonishing now we know she was running on empty – she demonstrated the drive to give it her all.