Moral injury

Each of us believes that, at our core, we are fundamentally ethical people. We always try to do the right thing. We have deeply held values and principles that we are not willing to compromise.

But sometimes we are thrust into situations where there appears to be no ‘right answer’ – where the best we can hope for is to take the ‘least bad’ option or, worse still, where we are forced to act against what we believe is right.

Moral injury is caused when we are compelled to act against what we believe is right in a high stakes situation.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why do good people do bad things?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Unconscious bias

Our brains are evolved to help us survive.

That means they take a lot of shortcuts to help us get through the day. These shortcuts, or heuristics, are vital. But they come at a cost. Learn what unconscious bias is and how you become aware of your own unconscious bias.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

Every time we make a decision, we change the world just a little bit.

This is why moral imagination plays a crucial role in good ethical decision making. It helps us appreciate other people’s perspective. And sometimes when we must make those decisions, they can be difficult, this is where moral courage comes into play.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

By checking in to our intuitions and using them to inform our judgements, we can come up with decisions that make sense, but also feel right.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to help your kid flex their ethical muscle

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

WATCHRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2023

The world around us is a smorgasbord of beliefs, claims, rules and norms about how we should live and behave.

It’s important to tease this jumble of ethical pressures apart so we can put them in their proper place. Otherwise, it can be hard to know what to do when some of these requirements contradict others. Let’s talk about three different categories of demands on how we should live: ethics, morality and law.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

WATCH

Relationships

Virtue ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Virtue ethics

What makes something right or wrong?

One of the oldest ways of answering this question comes from the Ancient Greeks. They defined good actions as ones that reveal us to be of excellent character.

What matters is whether our choices display virtues like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. Importantly, virtue ethics also holds that our actions shape our character. The more times we choose to be honest, the more likely we are to be honest in future situations – and when the stakes are high.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Deontology

What makes something right or wrong?

One answer comes from the work of German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who is considered the founder of an ethical theory called deontology. Deontology comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. It holds, quite simply, that actions are good or bad based on whether they fulfil universal moral duties.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Consequentialism

For lots of people, what makes a decision right or wrong depends on the outcome of that decision.

Does it increase or decrease the amount of happiness in the world? This kind of thinking is typical of consequentialism: an ethical school of thought that says what makes an action good or bad is, you guessed it, the consequences.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: Should I tell my student’s parents what they’ve been confiding in me?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

An ethics framework is a statement of an organisation’s purpose, values and principles.

It makes clear what they believe in and what standards they’ll uphold. It’s a roadmap to good decision making and, if it’s lived throughout the organisation. It’s also a guide to making an organisation the best version of itself.

Trying to make a decision without knowing your purpose, values and principles, is like being at sea without a rudder. They’ll be pushed around by the winds of our desires, mood, unconscious mind, group dynamics and social norms. The choices they make won’t really be their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Stopping domestic violence means rethinking masculinity

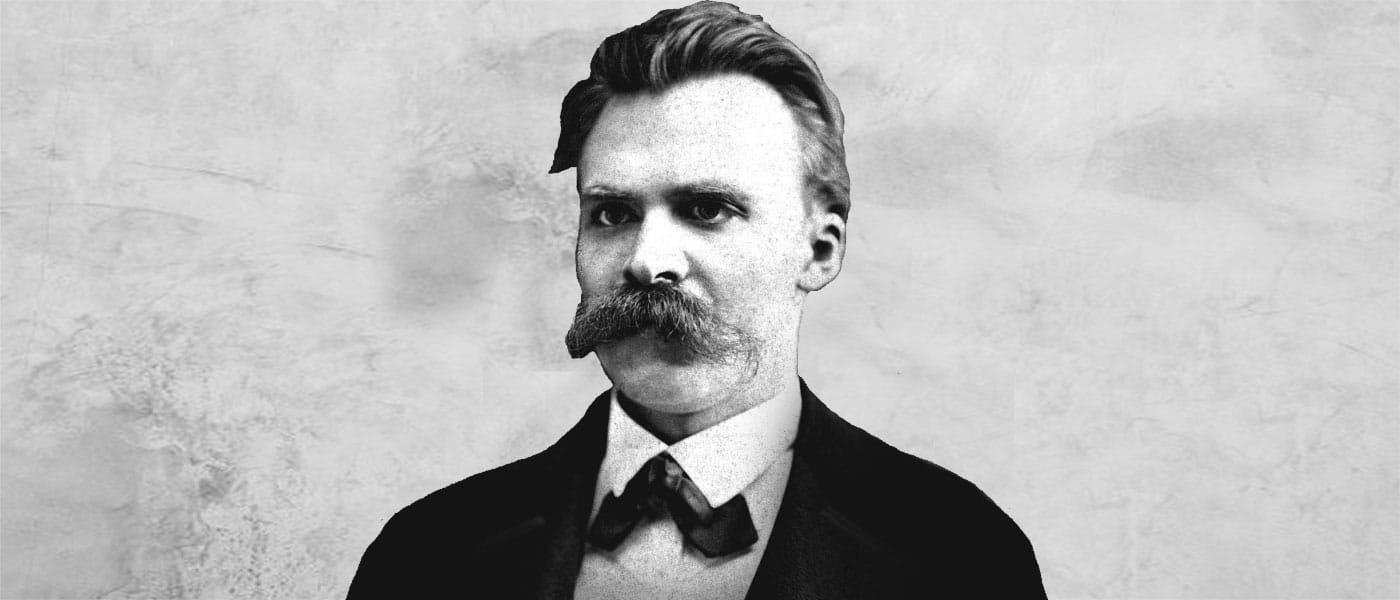

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What is ethics?

Ethics asks how we should live, what choices we should make and what makes our lives worth living.

It helps us define the conditions of a good choice and then figure out which of all the options available to us is the best one. Ethics is the process of questioning, discovering and defending our values, principles and purpose. It’s about finding out who we are and staying true to that in the face of temptations, challenges and uncertainty. It’s not always fun and it’s hardly ever easy, but if we commit to it, we set ourselves up to make decisions we can stand by, building a life that’s truly our own and a future we want to be a part of.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The Ethics of Online Dating

Explainer

Relationships