Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Imagine a large, cosmopolitan city, where people from uncountable backgrounds and with numerous beliefs all thrive together. People embrace different cultural traditions, speak varying languages, enjoy countless cuisines, and educate their children on diverse histories and practices.

This is the kind of pluralism that most people are familiar with, but a diverse and culturally integrated area like this is specifically an example of cultural pluralism.

Pluralism in a general sense says there can be multiple perspectives or truths that exist simultaneously, even if some of those perspectives are contradictory. It’s contrasted with monism, which says only one kind of thing exists; dualism, which says there are only two kinds of things (for example, mind and body); and nihilism, which says that no things exist.

So, while pluralism more broadly refers to a diversity of views, perspectives or truths, cultural pluralism refers specifically to a diversity of cultures that co-exist – ideally harmoniously and constructively – while maintaining their unique cultural identities.

Sometimes an entire country can be considered culturally pluralistic, and in other places there may be culturally pluralistic hubs (like states or suburbs where there is a thriving multicultural community within a larger more broadly homogenous area).

On the other end of the spectrum is cultural monism, the idea that a certain area or population should have only one culture. Culturally monistic places (for example, Japan or North Korea) rely on an implicit or explicit pressure for others to assimilate. Whereas assimilation involves the homogenisation of culture, pluralism encourages diversity, often embracing people of different ethnic groups, backgrounds, religions, practices and beliefs to come together and share in their differences.

A pluralistic society is more welcoming and supportive of minority cultures because people don’t feel pressured to hide or change their identities. Instead, diverse experiences are recognised as opportunities for learning and celebration. This invites travel and immigration, and translates into better mental health for migrants, the promotion of harmony and acceptance of others, and enhances creativity by exposing people to perspectives and experiences outside of their usual remit.

We also know what the alternative is in many cases. Australia has a dark history of assimilation practices, a symptom of racist, colonial perspectives that saw the decimation of First Nations people and their cultures. Cultural pluralism is one response to this sort of cultural domination that has been damaging throughout history and remains so in many places today.

However, there are plenty of ethical complications that arise in the pursuit of cultural plurality.

For example, sociologist Robert D. Putnam published research in 2007 that spoke about negative short-medium term effects of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. He found that, on average, trust, altruism and community cooperation was lower in these neighbourhoods, even between those of the same or similar ethnicities.

While Putnam denied that his findings were anti-multicultural, and argues that there are several positive long-term effects of diverse societies, the research does indicate some of the risks associated with cultural pluralism. It can take a large amount of effort and social infrastructure to build and maintain diverse communities, and if this fails or is done poorly it can cause fragmentation of cultural communities.

This also accords with an argument made by journalist David Goodhart, that says people are generally divided into “Anywheres” (people with a mobile identity) and “Somewheres” (people, usually outside of urban areas, who have marginalised, long-term, location-based identities). This incongruity, he says, accounts for things like Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, because they speak to the Somewheres who are threatened by changes to their status quo. Pluralism, Goodhart notes, risks overlooking the discomfort these communities face if they are not properly supported and informed.

Other issues with pluralism include the prioritisation of competing cultural values and traditions. What if one person’s culture is fundamentally intolerant of another person’s culture? This is something we see especially with cultures organised around or heavily influenced by religion. For example, Christianity and Islam are often at odds with many different cultures around issues of sexual preference and gendered rights and responsibilities.

If we are to imagine a truly culturally pluralistic society, how do we ethically integrate people who are intolerant of others?

Pluralism as a cultural ideal also has direct implications for things like politics and law, raising the age-old question about the relationship between morality and the law. If we want a pluralistic society generally, how do the variations in beliefs, values and principles translate into law? Is it better to have a centralised legal system or do we want a legal plurality that reflects the diversity of the area?

This does already exist in some capacity – many countries have Islamic courts that enforce Sharia law for their communities in addition to the overarching governmental law. This parallel law-enforcement also exists in some colonised countries, where parts of Indigenous law have been recognised. For example, in Australia, with the Mabo decision.

Another feature of genuine cultural pluralism that has huge ethical implications and considerations is diversity of media. This is the idea that there should be (that is, a media system that is not monopolised) and diverse representation in media (that is, media that presents varying perspectives and analyses).

Firstly, this ensures that media, especially news media, stays accountable through comparison and competition, rather than a select powerful few being able to widely disseminate their opinions unchecked. Secondly, it fosters a greater sense of understanding and acceptance by exposing people to perspectives, experiences and opinions that they might otherwise be ignorant or reflexively wary of. Thirdly, as a result, it reduces the risk that media, as a powerful disseminator of culture, could end up creating or reinforcing a monoculture.

While cultural pluralism is often seen as an obviously good thing in western liberal societies, it isn’t without substantial challenges. In the pursuit of tolerance, acceptance and harmony, we must be wary of fragmenting cultures and ensure that diverse communities have adequate social supports to thrive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Today feels eerily like the age that spawned the philosophy of radical freedom in defiance of the absurdity of life. Perhaps it’s time for a revival.

Parenting during the Covid-19 pandemic involved many new and unwelcome challenges. Some were obvious, practical things, like having the whole family suddenly working and learning under one roof, and the disruptions caused by lockdowns, isolation, and being physically cut off from extended family and friends.

But there were also what we might call the more existential challenges, the ones that engaged deeper questions of what to do in the face of radical uncertainty, absurdity and death. Words like “unprecedented” barely cover how shockingly the contingency of our social, economic and even physical lives were suddenly exposed. For me, one of the most confronting moments early in the pandemic was having my worried children ask me what was going to happen, and not being able to tell them. Feeling powerless and inadequate, all I could do was mumble something about it all being alright in the end, somehow.

I’m not sure how I did as a parent, but as a philosopher, this was a dismal failure on my part. After all, I’d been training for this moment since I was barely an adult myself. Like surprisingly many academic philosophers, I was sucked into philosophy via an undergraduate course on existentialism, and I’d been marinating in the ideas of Søren Kierkegaard in particular, but also figures like Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus, ever since. These thinkers had described better than anyone such moments of confrontation with our fragility in the face of an uncaring universe. Yet when “the stage sets collapse”, as Camus put it, I had no great insight to share beyond forced optimism.

In fairness, the existentialists themselves weren’t great at giving advice to young people either. During World War II, Sartre was approached by a young pupil wrestling with whether to stay and look after his mother or join the army to fight for France. Sartre’s advice in reply was “You are free, therefore choose” – classic Sartre, in that it’s both stirringly dramatic and practically useless. But then, that’s all Sartre really could say, given his commitment to the unavoidability of radical choice.

Besides, existentialism itself seems to have fallen out of style. For decades, fiction from The Catcher in the Rye through to Fight Club would valorise a certain kind of existential hero: someone who stood up against mindless conformity, exerting a freedom that others – the unthinking masses that Heidegger derisively called das Man, ‘the They’ – didn’t even realise they had.

These days, however, that sort of hero seems passé. We still tell stories of people rejecting inauthentic social messages and asserting their freedom, but of an altogether darker sort; think Joaquin Phoenix’s take on the Joker, for example. Instead of existentialist heroes, we’ve got nihilists.

I can understand why nihilism staged a comeback. In her classic existentialist manifesto, The Ethics of Ambiguity, Simone de Beauvoir tells us that “Nihilism is disappointed seriousness which has turned in upon itself.” For some time now, the 2020s have started to feel an awful lot like the 1920s: worldwide epidemic disease, rampant inflation and rising fascism. The future that was promised to us in the 1990s, one of ever-increasing economic prosperity and global peace (what Francis Fukuyama famously called the “end of history”) never arrived. That’s enough to disappoint anyone’s seriousness. Throw in the seemingly intractable threat of climate change, and the future becomes a source of inescapable dread.

But then, that is precisely the sort of context in which existentialism found its moment, in the crucible of occupation and global war. At its worst, existentialism can read like naïve adolescent posturing, the sort of all-or-nothing philosophy you can only believe in until you’ve experienced the true limits of your freedom.

At its best, though, existentialism was a defiant reassertion of human dignity in the face of absurdity and hopelessness. As we hurtle into planetary system-collapse and growing inequality and authoritarianism, maybe a new existentialism is precisely what we need.

Thankfully, then, not all the existential heroes went away.

Seeking redemption

During lockdowns, after the kids had gone to bed, I’d often retreat to the TV to immerse myself in Rockstar Games’ epic open-world first-person shooter Red Dead Redemption II. The game is both achingly beautiful and narratively rich, and it’s hard not to become emotionally invested in your character: the morally conflicted, laconic Arthur Morgan, an enforcer for the fugitive Van Der Linde gang in the twilight of the Old West. [Spoiler ahead.]

That’s why it’s such a gut-punch when, about two-thirds of the way through the game, Arthur learns he’s dying of tuberculosis. It feels like the game-makers have cheated you somehow. Game characters aren’t meant to die, at least not like this and not for good. Yet this is also one of those bracing moments of existential confrontation with reality. Kierkegaard spoke of the “certain-uncertainty” of death: we know we will die, but we do not know how or when. Suddenly, this certain-uncertainty suffuses the game-world, as your every task becomes one of your last. The significance of every decision feels amplified.

Arthur, in the end, grasps his moment. He commits himself to his task and sets out to right wrongs, willingly setting out to a final showdown he knows that, one way or another, he will not survive. It’s a long way from nihilism, and in ‘unprecedented’ times, it was exactly the existentialist tonic this philosopher needed.

We are, for good or ill, ‘living with Covid’ now. But the other challenges of our historical moment are only becoming more urgent. Eighty years ago, writing in his moment of oppression and despair, Sartre declared that if we don’t run away, then we’ve chosen the war. Outside of the Martian escape fantasies of billionaires, there is nowhere for us, now, to run. So perhaps the existentialists were right: we need to face uncomfortable truths, and stand and fight.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

BY Pat Stokes

Dr Patrick Stokes is a senior lecturer in Philosophy at Deakin University. Follow him on Twitter – @patstokes.

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 9 AUG 2023

If we are to engage with the ethical complexity of the world, we need to learn how to hold two contradictory judgements in our mind at the same time.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

– Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

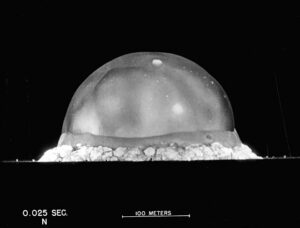

A fraction of a second after the first atomic bomb was detonated in New Mexico in 1945, a dense blob of superheated gas with a temperature of over 20,000 degrees expanded to a diameter of 250 metres, casting a light brighter than the sun and illuminating the surrounding valley as if it were daytime. We know what the atomic blast looked like at this nascent moment because there is a black and white photograph of it, taken using a specialised high-speed camera developed just for this test.

I vividly remember seeing this photo for the first time in a school library book. I spent long stretches contemplating the otherworldly beauty of the glowing sphere, marvelling at the fundamental physical forces on display, awed and diminished by their power. Yet I was also deeply troubled by what the image represented: a weapon designed for indiscriminate killing and the precursor to the device dropped on Nagasaki, taking over 200,000 lives – most civilians.

I’m not the only one to have mixed feelings about the atomic test. The “father” of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer – the subject of the new Christopher Nolan film – expressed pride at the accomplishment of his team in developing a weapon that could end a devastating war, but he also experienced tremendous guilt at starting an arms race that could end humanity itself. He reportedly told the U.S. President Harry S. Truman that his involvement in developing the atomic bomb left him feeling like he had blood on his hands.

In expressing this, Oppenheimer was displaying ethical ambivalence, where he held two opposing views at the same time. Today, we might regard Oppenheimer and his legacy with similar ambivalence.

This is not necessarily an easy thing to do; our minds often race to collapse ambivalence into certainty, into clean black and white. But it’s also an important ethical skill to develop if we’re to engage with the complexities of a world rendered in shades of grey.

In all things good, in all things bad

It’s rare that we come across someone or something that is entirely good or entirely bad. Fossil fuels have lit the darkness and fended off the cold of winter, but they also contribute to destabilising the world’s climate. Natural disasters can cause untold damage and suffering, but they can also awaken the charity and compassion within a community. And many of those who have offered the greatest contributions to art, culture or science have also harboured hidden vices, such as maintaining abusive relationships in private.

When confronted by these conflicted cases, we often enter a state of cognitive dissonance. Contemplating the virtues and vices of fossil fuels at the same time, or appreciating the art of Pablo Picasso while being aware of his relationship towards women, is akin to looking at the word “red” written in blue ink. Our minds recoil from the contradiction and race to collapse it into a singular judgement: good or bad.

But in our rush to escape the discomfort of dissonance, we can cut ourselves off from the full ethical picture. If we settle only on the bad then we risk missing out on much that is good, beautiful or enriching. The paintings of Picasso still retain their artistic virtues despite our opinion of its creator. Yet if we settle only on the good, then we risk excusing much that is bad. Just because we appreciate Picasso’s portraits doesn’t mean we should endorse his treatment of women, even if his relationships with those women informed his art.

Ambivalence doesn’t mean withholding judgement; we can still decide that the balance falls clearly on one side or the other. But even if we do judge something as being overall bad, we can still appreciate the good in it.

The key is to learn how to appreciate without endorsement. Indeed, how to appreciate and condemn simultaneously.

This might change the way we represent some historical figures. If we want to acknowledge both the accomplishments and the colonial consequences of figures like James Cook, that might mean doing so in a museum rather than erecting statues, which by their nature are unambiguous artifacts intended to elevate an individual in the public eye.

Despite our minds yearning to collapse the discomfort of ambivalence into certainty, if we are to engage with the full ethical complexity of world and other people, then we need to be willing to embrace good and bad simultaneously and with nuance, even if that means holding contradictory attitudes at the same time.

So, while I remain committed to the view that nuclear weapons represent an unacceptable threat to the future of humanity, I still appreciate the beauty of that photo of the first atomic test. It does feel contradictory to hold these two views simultaneously. Very well, I contradict myself. I, like every facet of reality, contain multitudes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Barbie and what it means to be human

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 7 AUG 2023

It was with a measure of apprehension that I recently travelled to the cinema to watch Greta Gerwig’s Barbie.

I was conscious of being an atypical audience member – with most skewing younger, female and adorned in pink (I missed out on all three criteria). However, having read some reviews (both complimentary and critical) I was expecting a full-scale assault on the ‘patriarchy’ – to which, on appearances alone, I could be said to belong.

Warning: This article contains spoilers for the film Barbie

However, Gerwig’s film is far more interesting. Not only is it not a critique of patriarchy as a singular evil, but it raises deep questions about what it means to be human (whatever your sex or gender identity). And it does this all with its tongue firmly planted in the proverbial cheek; laughing not only at the usual stereotypes but, along the way, at itself.

The first indication that this film intends to subvert all stereotypes comes in the opening sequence – an homage to the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s iconic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rather than encountering a giant black ‘obelisk’ that reorients the history of humankind, a group of young girls wake to find a giant Margot Robbie looming over them in the form of ‘Stereotypical Barbie’. Until that time, the girls have been restricted to playing with baby dolls and learning the stereotypical roles allotted to women in a male-dominated world.

What happens next is instructive. Rather than simply putting aside the baby dolls in favour of the new adult form represented by Barbie, the girls embark on a savage work of destruction. They dismember the baby dolls, crush their skulls, grind them into the dirt. This is not a gentle awakening into something that is more ‘pure’ than what came before. From the outset, we are offered an image of humanity that is not one in which the divide between ‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘dominant’ and submissive’, ‘peaceful’ and ‘violent’ is neatly allocated in favour of one sex or another. Rather, virtues and vices are shown to be evenly distributed across humanity in all its variety.

That the violent behaviour of the little girls is not an aberration is made clear later in the film when we are introduced to ‘Weird Barbie’. She lives on the margins of ‘Barbieland’ – both an outcast and a healer – whose status has been defined by her broken (imperfect) condition. The damage done to ‘Weird Barbie’ is, again, due to mistreatment by a subset of girls who treat Barbie in the same way depicted in the opening scenes. Then there is ‘Barbieland’ itself – a place of apparent perfection … unless you happen to be a ‘Ken’. Here, the ‘Patriarchy’ has been replaced by a ‘Matriarchy’ that is invested with all of the flaws of its male counterpart.

In Barbieland, Kens have no status of their own. Rather, they are mere cyphers – decorative extensions of the Barbies whom they adorn. For the most part, they are frustrated by, but ultimately accepting of, their status. The conceit of the film is an obvious one: Barbieland is the mirror image of the ‘real world,’ where patriarchy reigns supreme. Indeed, the Barbies (in all their brilliant variety) believe that their exemplary society has changed the real world for the better, liberating women and girls from all male oppression.

Alas, the real world is not so obliging – as is soon discovered when the two worlds intersect. There, Stereotypical Barbie (suffering from a bad case of flat feet) and Stereotypical Ken are exposed to the radically imperfect society that is the product of male domination. Much of what they find should be familiar to us. The film does a brilliant job of lampooning what we might take for granted. Even the character of male-dominated big business comes in for a delightful serve. The target is Mattel (which must be commended for its willingness to allow itself to be exposed to ridicule – even in fictional form).

Unfortunately, Ken (played by Ryan Gosling) learns all the wrong lessons. Infected by the ideology of Patriarchy (which he associates with male dominance and horse riding) he returns to Barbieland to ‘liberate’ the Kens. The contagion spreads – reversing the natural order; turning the ‘Barbies’ into female versions of the Kens of old.

Fortunately, all is eventually made right when Margot Robbie’s character, with a mother and daughter in tow, returns to save the day.

But the reason the film struck such a chord with me, is because it raises deeper questions about what it means to be human.

It is Stereotypical Barbie who finally liberates Stereotypical Ken by leading him to realise that his own value exists independent of any relationship to her. Having done so, Barbie then decides to abandon the life of a doll to become fully human. However, before being granted this wish by her creator (in reality, a talented designer and businesswoman of somewhat questionable integrity) she is first made to experience what the choice to be human entails. This requires Barbie to live through the whole gamut of emotions – all that comes from the delirious wonder of human life – as well as its terrors, tragedies and abiding disappointments.

This is where the film becomes profound.

How many of us consciously embrace our humanity – and all of the implications of doing so? How many of us wonder about what it takes to become fully human? Gerwig implies that far fewer of us do so than we might hope.

Instead, too many of us live the life of the dolls – no matter what world we live in. We are content to exist within the confines of a box; to not think or feel too deeply, to not have our lives become more complicated as when happens when the rules and conventions – the morality – of the crowd is called into question by our own wondering.

Don’t be put off by the marketing puffery; with or without the pink, this is a film worth seeing. Don’t believe the gripes of ‘anti-woke’, conservative commentators. They attack a phantom of their own imagining. This film is aware without being prescriptive. It is fair. It is clever. It is subtle. It is funny. It never takes itself too seriously. It is everything that the parody of ‘woke’ is not.

It is ultimately an invitation to engage in serious reflection about whether or not to be fully human – with all that entails. It is an invitation that Barbie accepts – and so should we.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Get mad and get calm: the paradox of happiness

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Agape

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 7 AUG 2023

“I have blood on my hands.” This is what Robert Oppenheimer, the mastermind behind the Manhattan Project, told US President Harry Truman after the bombs he created were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing over an estimated 226,000 people.

The President reassured him, but in private was incensed by the ‘cry-baby scientist’ for his guilty conscience and told Dean Acheson, his Secretary of State, “I don’t want to see that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

With the anniversary of the bombings this week while Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is in cinemas, it is a good moment to reflect on the two people most responsible for the creation and use of nuclear weapons: one wracked with guilt, the other with a clean conscience.

Who is right?

In his speech announcing the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Truman provided the base from which apologists sought to defend the use of nuclear weapons: it “shortened the agony of war.”

It is a theme developed by American academic Paul Fussell in his essay Thank God for the Atom Bomb. Fussell, a veteran of the European Theatre, defended the use of nuclear weapons because it spared the bloodshed and trauma of a conventional invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Military planners believed that this could have resulted in over a million causalities and hundreds of thousands of deaths of service personnel, to say nothing of the effect on Japanese civilians. In the lead up to the invasion the Americans minted half a million Purple Hearts, medals for those wounded in battle; this supply has lasted through every conflict since. We can see here the simple but compelling consequentialist reasoning: war is hell and anything that brings it to an end is worthwhile. Nuclear weapons, while terrible, saved lives.

The problem is that this argument rests on a false dichotomy. The Japanese government knew they had lost the war; weeks before the bombings the Emperor instructed his ministers to seek an end to the war via the good offices of the Soviet Union or another neutral state. There was a path to a negotiated peace. The Allies, however, wanted unconditional surrender.

We might ask whether this was a just war aim, but even if it was, there were alternatives: less indiscriminate aerial attacks and a naval blockade of war materials into Japan would have eventually compelled surrender. The point here isn’t to play at ‘armchair general’, but rather to recognise that the path to victory was never binary.

However, this reply is inadequate, because it doesn’t address the general question about the use of nuclear weapons, only the specific instance of their use in 1945. There is a bigger question: is it ever ethical to use nuclear weapons. The answer must be no.

Why?

Because, to paraphrase American philosopher Robert Nozick, people have rights and there are certain things that cannot be done to them without violating those rights. One such right must be against being murdered, because that is what the wrongful killing of a person is. It is murder. If we have these rights, then we must also be able to protect them and just as individuals can defend themselves so too can states as the guarantor of their citizen’s rights. This is a standard categorical check against the consequentialist reasoning of the military planners.

The horror of war is that it creates circumstances where ordinary ethical rules are suspended, where killing is not wrongful.

A soldier fighting in a war of self-defence may kill an enemy soldier to protect themselves and their country. However, this does not mean that all things are permitted. The targeting of non-combatants such as wounded soldiers, civilians, and especially children is not permitted, because they pose no threat.

We can draw an analogy with self-defence: if someone is trying to kill you and you kill them while defending yourself you have not done anything wrong, but if you deliberately killed a bystander to stop your attacker you have done something wrong because the bystander cannot be held responsible for the actions of your assailant.

It is a terrible reality that non-combatants die in war and sometimes it is excusable, but only when their deaths were not intended and all reasonable measures were taken to prevent them. Philosopher Michael Walzer calls this ‘double intention’; one must intend not to harm non-combatants as the primary element of your act and if it is likely that non-combatants will be collaterally harmed you must take due care to minimise the risks (even if it puts your soldiers at risk).

Hiroshima does not pass the double intention test. It is true that Hiroshima was a military target and therefore legitimate, but due care was not taken to ensure that civilians were not exposed to unnecessary harm. Nuclear weapons are simply too indiscriminate and their effects too terrible. There is almost no scenario for their use that does not include the foreseeable and avoidable deaths of non-combatants. They are designed to wipe out population centres, to kill non-combatants. At Hiroshima, for every soldier killed there were ten civilian deaths. Nuclear weapons have only become more powerful since then.

Returning to Oppenheimer and Truman, it is impossible not to feel that the former was in the right. Oppenheimer’s subsequent opposition to the development of more powerful nuclear weapons and support of non-proliferation, even at the cost of being targeted in the Red Scare, was a principled attempt to make amends for his contribution to the Manhattan Project.

The consequentialist argument that the use of nuclear weapons was justified because in shortening the war it saved lives and minimised human suffering can be very appealing, but it does not stand up to scrutiny. It rests on an oversimplified analysis of the options available to allied powers in August 1945; and, more importantly, it is an intrinsic part of the nature of nuclear weapons that their use deliberately and avoidably harms non-combatants.

If you are still unconvinced, imagine if the roles were reversed in 1945: one could easily say that Sydney or San Francisco were legitimate targets just like Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If the Japanese dropped an atomic bomb on Sydney Harbour on the grounds that it would have compelled Australia to surrender thereby ending the “agony of war”, would we view this as ethically justifiable or an atrocity to tally alongside the Rape of Nanking, the death camps of the Burma railroad, or the terrible human experiments conducted by Unit 731? It must be the latter, because otherwise no act, however terrible, can be prohibited and war truly becomes hell.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Reports

Science + Technology

Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

READ

Society + Culture

10 dangerous reads for FODI24

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

While the stories of Virginia Woolf are not traditionally considered as works of philosophy, her literature has a lot to teach us about self-identity, transformation, and our relationship to others.

“A million candles burnt in him without his being at the trouble of lighting a single one.” – Virginia Woolf, Orlando

Woolf was not a philosopher. She was not trained as such, nor did she assign the title to herself, and she did not produce work which follows traditional philosophical construction. However, her writing nonetheless stands as comprehensive, albeit unique, work of philosophy.

Woolf’s books, such as Orlando, The Waves, and Mrs Dalloway, are philosophical inquiries into ideas of the limits of the self and our capacity for transformation. At some point we all may feel a bit trapped in our own lives, worrying that we are not capable of making the changes needed to break free from routine, which in time has turned mundane.

Woolf’s characters and stories suggest that our own identities are endlessly transforming, whether we will them to or not.

More classical philosophers, like David Hume, explore similar questions in a more forthright manner. Also reflecting on matters of the stability of personal identity, Hume writes in his A Treatise of Human Nature:

“Our eyes cannot turn in their sockets without varying our perceptions. Our thought is still more variable than our sight; and all our other senses and faculties contribute to this change; nor is there any single power of the soul, which remains unalterably the same, perhaps for one moment. The mind is a kind of theatre…”

Woolf’s books make similar arguments. Rather than stating them in these explicit forms, she presents us with characters who depict the experience that Hume describes. Woolf’s surrealist story, Orlando, follows the long life of a man who one day awakens to find themselves a woman. Throughout we are made privy to the way the world and Orlando’s own mind alters as a result:

“Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than to merely keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.”

When Hume describes the mind as a theatre, he suggests there is no core part of ourselves that remains untouched by the inevitability of layered experience. We may be moved to change our fashion sense and, as a result, see the world treat us differently in response to this change. In turn, we are transformed, either knowingly or unknowingly, by whatever this new treatment may be.

Hume suggests that, while just as many different acts take place on a single stage, our personal identities also ebb and flow depending on whatever performance may be put before us at any given time. After all, the world does not merely pass us by; it speaks to us, and we remain entangled in conversation.

While Hume constructs this argument in a largely classical philosophical form, Woolf explores similar themes in her works through more experimental ways:

“A million candles burnt in him”, she writes in Orlando, “without his being at the trouble of lighting a single one.”

Using the gender transforming character of Orlando, Woolf examines identity, its multiplicity, and how, despite its being an embodied sensation, our sense of self both wavers and feels largely out of our control. In the novel, any complexities in Orlando’s change of gender are overshadowed by the multitude of other complexities in the many transformations that one embarks in life.

Throughout the book, readers are also given the opportunity to reflect on their own conceptions of self-identity. Do they also feel this ever-changing myriad of passions and selves within them? The character of Orlando allows readers to consider whether they also feel as though the world oftentimes presents itself unbidden, with force, shuffling the contents of their hearts and minds again and again. While Hume’s Treatise aims to convince us that who we are is constantly subject to change, Orlando gives readers the chance to spend time with a character actively embroiled in these changes.

A Room of One’s Own presents a collated series of Woolf’s essays which explore the topics of women and fiction. Though non-fictional, and evidently a work of critical theory, Woolf meditates on her own experience of acquiring a large, lifetime inheritance. She reflects on the ways in which her assured income not only materially transformed her capacities to pursue creative writing, but also how it radically transformed her perceptions of the individuals and social structures surrounding her:

“No force in the world can take from me my [monthly] five hundred pounds. Food, house and clothing are mine for ever. Therefore not merely do effort and labour cease, but also hatred and bitterness. I need not hate any man; he cannot hurt me. I need not flatter any man; he has nothing to give me. So imperceptibly I found myself adopting a new attitude towards the other half of the human race. It was absurd to blame any class or any sex, as a whole. Great bodies of people are never responsible for what they do. They are driven by instincts which are not within their control. They too, the patriarchs, the professors, had endless difficulties, terrible drawbacks to contend with.”

While Hume tells us, quite explicitly, about the fluidity of the self and of the mind’s susceptibility to its perceptual encounters, Woolf presents her readers with a personal instance of this very phenomenon. The acquisition of a stable income meant her thoughts about her world shifted. Woolf’s material security afforded her the freedom to choose how she interacts with those around her. Free from dependence, hatred and bitterness no longer preoccupied her mind, leaving space for empathy and understanding. The social world, which remained largely unchanged, began telling her a different story. With another candle lit, and the theatre of her mind changed, the perception of the world before her was also transformed, as was she.

If a philosopher is an individual who provokes their audiences to think in new ways, who poses both questions and ways in which those questions may be responded to, we can begin to see the philosophy of Virginia Woolf. Woolf’s personal philosophical style is one that does not set itself up for a battle of agreement or disagreement. Instead, it contemplates ideas in theatrical, enlivened forms which are seemingly more preoccupied with understanding and exploration rather than mere agreement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

What is all this content doing to us?

Three years ago, the eye-wateringly expensive television show See aired. Starring Jason Momoa, the budget for the show tapped out at around a million dollars per episode, a ludicrous amount of money even in today’s age.

As to what See is about – well, that’s not really worth discussing. Because chances are you haven’t seen it, and, in all likelihood, you’re not going to. What matters is that this was a massive piece of content that sank without a single trace. Ten years ago, a product like that would have been a big deal, no matter whether people liked it or not. It would have been, regardless of reception, an event. Instead, it’s one of a laundry list of shows that feel like they simply don’t exist.

This is what it means to be in the world of peak content. Every movie you loved as a kid is being rebooted; every franchise is being restarted; every actor you have even a passing interest in has their own four season long show.

But what is so much content doing to us? And how is it affecting the way we consider art?

The tyranny of choice

If you own a television, chances are you have found yourself parked in front of it, armed with the remote, at a complete loss as to what to watch. Not because your choices are limited. But because they are overwhelmingly large.

This is an example of what is known as “the tyranny of choice.” Many of us might believe that more choice is necessarily better for us. As the philosopher Renata Salecl outlines, if you have the ability to choose from three options, and one of them is taken away, most of us would assume we have been harmed in some way. That we’ve been made less free.

But the social scientists David G. Myers and Robert E. Lane have shown that an increase in choice tends to lead to a decrease in overall happiness. The psychologist Barry Schwartz has explained this through what he understands as our desire to “maximalise” – to get the best out of our decisions.

And yet trying to decide what the best decision will be takes time and effort. If we’re doing that constantly, forever in the process of trying to analyse what will be best for us, we will not only wear ourselves down – we’ll also compare the choice we made against the other potential choices we didn’t take. It’s a kind of agonising “grass is always greener” process, where our decision will always seem to be the lesser of those available.

The sea of content we swim in is therefore work. Choosing what to watch is labour. And we know, in our heart of hearts, that we probably could have chosen better – that there’s so much out there, that we’re bound to have made a mistake, and settled for good when we could have watched great.

The big soup of modern life

When content begins to feel like work, it begins to feel like… well, everything else. So much of our lives are composed of labour, both paid and unpaid. And though art should, in its best formulation, provide transcendent moments – experiences that pull us out of ourselves, and our circumstances – the deluge of content has flattened these moments into more capitalist stew.

Remember how special the release of a Star Wars movie used to feel? Remember the magic of it? Now, we have Star Wars spin-offs dropping every other month, and what was once rare and special is now an ever-decreasing series of diminishing returns. And these diminishing returns are not being made for the love of it – they’re coming from a cynical, money-grubbing place. Because they need to make money, due in no small part to their ballooning budgets, they are less adventurous, rehashing past story beats rather than coming up with new ones; playing fan service, instead of challenging audiences. After all, it’s called show business for a reason, and mass entertainment is profit-driven above all else, no matter how much it might enrich our lives.

This kind of nullifying sameness of content, made by capitalism, was first outlined by the philosophers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. “Culture now impresses the same stamp on everything,” they wrote in Dialectic of Enlightenment. “Films, radio and magazines make up a system which is uniform as a whole and in every part.”

Make a choice

So, what is to be done about all this? We obviously can’t stop the slow march of content. And we wouldn’t even want to – art still has the power to move us, even as it comes in a deluge.

Of course, being more aware of what we consume, and when we consume it, and why won’t stop capitalism. But it will change our relationship with art.

The answer, perhaps, is intentionality. This is a mindfulness practice – thinking about what we’re doing carefully, making every choice with a weight and thrust. Not doing anything passively, or just because you can. But applying ourselves fully to what we decide, and accepting that is the decision that we have made.

The filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard once said that at the cinema, audience goers look up, and at home, watching TV, audience goers look down. As it turns out, we look down at far too much these days, regardless of whether we’re at home or in the cinema. We take content for granted; allow it to blare out across us; reduce it to the status of wallpaper, just something to throw on and leave in the background. It becomes less special, and our relationship to it becomes less special too.

The answer: looking up. Of course, being more aware of what we consume, and when we consume it, and why won’t stop capitalism. But it will change our relationship with art. It will make us decision-makers – active agents, who engage seriously with content and learn things through it about our world. It will preserve some of that transcendence. And it will reduce the exhausting tyranny of choice, and make these decisions feel impactful.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JUL 2023

Judith Jarvis Thomson (1929-2020) is one of the most influential ethicists and metaphysicians of the 20th century. She’s known for changing the conversation around abortion, as well as modernising what we now know as the trolley problem.

Thomson was born in New York City on October 4th, 1929. Her mother was Catholic of Czech heritage and her father was Jewish, who both met at a socialist summer camp. While her parents were religious, they didn’t impose their beliefs on her.

At the age of 14, Thomson converted to Judaism, after her mother died and her father remarried a Jewish woman two years later. As an adult, she wasn’t particularly religious but she did describe herself publicly as “feel[ing] concern for Israel and for the future of the Jewish people.”

In 1950, Thomson graduated from Barnard College with a Bachelor of Arts (BA), majoring in philosophy, and then received a second BA in philosophy from Cambridge University in England in 1952. She then went on to receive her Masters in philosophy from Cambridge in 1956 and her PhD in philosophy from Columbia University in New York in 1959.

Violinists, trolleys and philosophical work

Even though she had received her PhD from Columbia, the philosophy department wouldn’t keep her as a professor as they didn’t hire women. In 1962, she began working as an assistant professor at Barnard college, though she later moved to Boston University and then MIT with her husband, James Thomson, for the majority of her career.

Thomson is most famous for her thought experiments, especially the violinist case and the trolley problem. In 1971, Thomson published her book A Defense of Abortion, which presented a new kind of argument for why abortions are permissible during a time of heightened debate in the US as a result of the second wave feminist movement. Arguments that defended a woman’s right to an abortion circulated feminist publications and eventually led to the Supreme Court ruling in favour of Roe v. Wade (1973).

“Opponents of abortion commonly spend most of their time establishing that the foetus is a person, and hardly any time explaining the step from there to the impermissibility of abortion.” – Judith Jarvis Thomson

The famous violinist case asks us to imagine if it is permissible to “unplug” ourselves from a famous violinist, even if it is only for nine months and being plugged in is the only thing keeping them alive. As Thomas Nagel said, “she expresses very clearly the essentially negative character of the right to life, which is that it’s a right not to be killed unjustly, and not a right to be provided with everything necessary for life.” To this day, the violinist case is taught in classrooms and recognised as one of the most influential thought experiments arguing for the permissibility of abortion.

Thomson is famous for another famous thought experiment, the trolley problem. In her 1976 paper “Killing, Letting Die and the Trolley Problem,” Judith Jarvis Thomson articulates a famous thought experiment, first imagined by Philippa Foot, that encourages us to think about the moral relevance of killing people, as opposed to letting people die by doing nothing to save them.

In the trolley problem thought experiment, a runaway trolley will kill five innocent people unless someone pulls a lever. If the lever is pulled, the trolley will divert onto a different track and only one person will die. As an extension to Foot’s argument, Thomson asks us to think if there is something different about pushing a large man off a bridge, thereby killing him, to prevent five people from dying from the runaway trolley. Why does it feel different to pull a lever rather than push a person? Both have the same potential outcomes and distinguish between killing a person and letting a person die.

In the end, what Thomson finds is that oftentimes, the action as well as the outcome are morally relevant in our decision making process.

Legacy

Thomson’s extensive philosophical career hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2012, she was awarded the American Philosophical Association’s prestigious Quinn Prize for her “service to philosophy and philosophers.” In 2015, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Cambridge, and then in 2016 she was awarded another honorary doctorate from Harvard.

Thomson continues to inspire women in philosophy. As one of her colleagues, Sally Haslanger, says: “she entered the field when only a tiny number of women even considered pursuing a career in philosophy and proved beyond doubt that a woman could meet the highest standards of philosophical excellence … She is the atomic ice-breaker for women in philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

COP26: The choice of our lives

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Rawls

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lies corrupt democracy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 6 JUL 2023

The billionaire has become a ubiquitous part of life in the 21st century.

In the past many of the ultra-wealthy were content to influence politics behind the scenes in smoke-filled rooms or limit their public visibility to elite circles by using large donations to chisel their names onto galleries and museums. Today’s billionaires are not so discrete; they are more overtly influential in the world of politics, they engage in eye-catching projects such as space and deep-sea exploration, and have large, almost cult-like, followings on social media.

Underpinning the rise of this breed of billionaire is the notion that there is something special about the ultra-wealthy. That in ‘winning’ capitalism they have demonstrated not merely business acumen, but a genius that applies to the human condition more broadly. This ‘epistemic privilege’ casts them as innovators whose curiosity will bring benefits to the rest of us and the best thing that we normal people can do is watch on from a distance. This attitude is embodied in the ‘Silicon Valley Libertarianism’ which seeks to liberate technology from the shackles imposed on it by small-minded mediocrities such as regulation. This new breed seeks great power without much interest in checks on the corresponding responsibility.

Is this OK? Curiosity, whether about the physical world or the world of ideas, seems an uncontroversial virtue. Curiosity is the engine of progress in science and industry as well as in society. But curiosity has more than an instrumental value. Recently, Lewis Ross, a philosopher at the London School of Economics, has argued that curiosity is valuable in itself regardless of whether it reliably produces results, because it shows an appreciation of ‘epistemic goods’ or knowledge.

We recognise curiosity as an important element of a good human life. Yet, it can sometimes mask behaviour we ought to find troubling.

Hubris obviously comes to mind. Curiosity coupled with an outsized sense of one’s capabilities can lead to disaster. Take Stockton Rush, for example, the CEO of OceanGate and the author of the tragic sinking of the Titan submarine. He was quoted as saying: “I’d like to be remembered as an innovator. I think it was General MacArthur who said, ‘You’re remembered for the rules you break’, and I’ve broken some rules to make this. I think I’ve broken them with logic and good engineering behind me.” The result was the deaths of five people.

While hubris is a foible on a human scale, the actions of individuals cannot be seen in isolation from the broader social contexts and system. Think, for example, of the interplay between exploration and empire. It is no coincidence that many of those dubbed ‘great explorers’, from Columbus to Cook, were agents for spreading power and domination. In the train of exploration came the dispossession and exploitation of indigenous peoples across the globe.

A similar point could be made about advances in technology. The industrial revolution was astonishing in its unshackling of the productive potential of humanity, but it also involved the brutal exploitation of working people. Curiosity and innovation need to be careful of the company they keep. Billionaires may drive innovation, but innovation is never without a cost and we must ask who should bear the burden when new technology pulls apart the ties that bind.

Yet, even if we set aside issues of direct harm, problems remain. Billionaires drive innovation in a way that shapes what John Rawls called the ‘basic structure of society’. I recently wrote an article for International Affairs giving the example of the power of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in global health. Since its inception the Gates Foundation has become a key player in global health. It has used its considerable financial and social power to set the agenda for global health, but more importantly it has shaped the environment in which global health research occurs. Bill Gates is a noted advocate of ‘creative capitalism’ and views the market as the best driver for innovation. The Gates Foundation doesn’t just pick the type of health interventions it believes to be worth funding, but shapes the way in which curiosity is harnessed in this hugely important field.

This might seem innocuous, but it isn’t. It is an exercise of power. You don’t have to be Michel Foucault to appreciate that knowledge and power are deeply entwined. The way in which Gates and other philanthrocapitalists shape research naturalises their perspective. It shapes curiosity itself. The risk is that in doing so, other approaches to global health get drowned out by focussing on hi-tech market driven interventions favoured by Gates.

The ‘law of the instrument’ comes to mind: if the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail. By placing so much faith in the epistemic privilege of billionaires, we are causing a proliferation of hammers across the various problems of the world. Don’t get me wrong, there is a place for hammers, they are very useful tools. However, at the risk of wearing this metaphor out, sometimes you need a screwdriver.

Billionaires may be gifted people, but they are still only people. They ought not to be worshipped as infallible oracles of progress, to be left unchecked. To do so exposes the rest of us to the risk of making a world where problems are seen only through the lens created by the ultra-wealthy – and the harms caused by innovation risk being dismissed merely as the cost of doing business.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

We are turning into subscription slaves

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

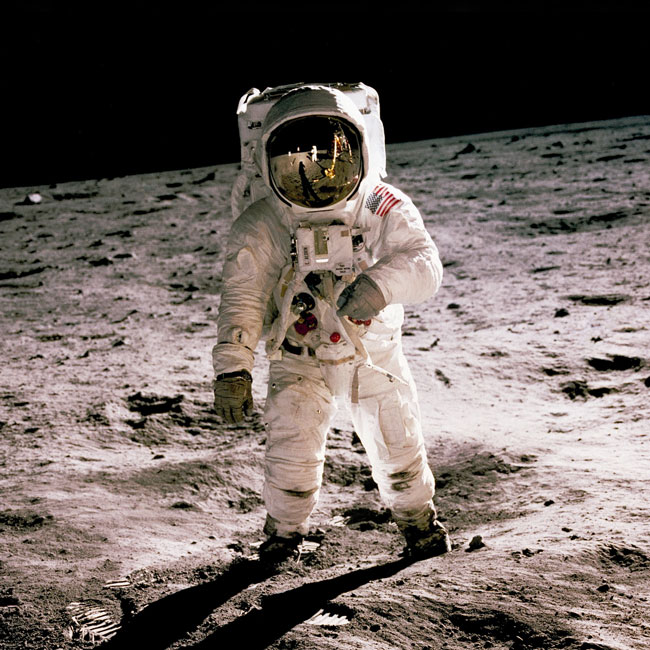

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 3 JUL 2023

Nothing can or should diminish the good done by Gladys Berejiklian. And nothing can or should diminish the bad. One does not cancel the other. Both are true. Both should be acknowledged for what they are.

Yet, in the wake of Independent Commission Against Corruption’s finding that the former premier engaged in serious corrupt conduct, her political opponent, Premier Chris Minns, has refused to condemn the conduct that gave rise to this finding. Other politicians have gone further, putting personal and political allegiance ahead of sound principle to promote a narrative of denial and deflection.

Political corruption is like a highly contagious virus that infects the cells of the brain. It tends to target people who believe their superior virtue makes them immune to its effects. It protects itself from detection by convincing its hosts that they are in perfect ethical health, that the good they do outweighs the harm corruption causes, that noble intentions excuse dishonesty and that corruption only “counts” when it amounts to criminal conduct.

By any measure, Berejiklian was a good premier. Her achievements deserve to be celebrated. I am also certain that she is, at heart, a decent person who sincerely believes she always acted in the best interests of the people of NSW. By such means, corruption remains hidden – perhaps even from the infected person and those who surround them.

In painstaking legal and factual detail, those parts of the ICAC report dealing with Berejiklian reveal a person who sabotaged her own brilliant career, not least by refusing to avail herself of the protective measures built into the NSW Ministerial Code of Conduct. The code deals explicitly with conflicts of interest. In the case of a premier, it requires that a conflict be disclosed to other cabinet ministers so they can determine how best to manage the situation.

The code is designed to protect the public interest. However, it also offers protection to a conflicted minister. Yet, in violation of her duty and contrary to the public interest, Berejiklian chose not to declare her obvious conflict.

At the height of the COVID pandemic, did we excuse a person who, knowing themselves to be infected by the virus, continued to spread the disease because they were “a good person” doing ‘a good job’? Did we turn a blind eye to their disregard for public health standards just because they thought they knew better than anyone else? Did it matter that wilfully exposing others to risk was not a criminal offence? Of course not. They were denounced – not least by the leading politicians of the day.

But in the case of Berejiklian, what we hear in reply is the voice of corruption itself – the desire to excuse, to diminish, to deflect. Those who speak in its name may not even realise they do so. That is how insidious its influence tends to be. Its aim is to normalise deviance, to condition all whom it touches to think the indefensible is a mere trifle.

This is especially dangerous in a democracy. When our political leaders downplay conflicts of interest in the allocation of public resources, they reinforce the public perception that politicians cannot be trusted to use public power and resources solely in the public interest.

Our whole society, our economy, our future rest on the quality of our ethical infrastructure. It is this that builds and sustains trust. It is trust that allows society to be bold enough to take risks in the hope of a better future. We invest billions building physical and technical infrastructure. We invest relatively little in our ethical infrastructure. And so trust is allowed to decay. Nothing good can come of this.

When our ethical foundations are treated as an optional extra to be neglected and left to rot, then we are all the poorer for it.

What Gladys Berejiklian did is now in the past. What worries me is the uneven nature of the present response. Good people can make mistakes. Even the best of us can become the authors of bad deeds. But understanding the reality of human frailty justifies neither equivocation nor denial when the virus of corruption has infected the body politic.

This article was originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights