Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 31 MAY 2020

Having navigated the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic with a relatively low loss of life, Australians are hoping to return to a more familiar pattern of living.

For many of those Australians, they seek an illusion. The world to which they return will have been fundamentally altered – not by the virus – but by the decisions we have taken in response to its emergence.

At one point, we feared those decisions would be especially difficult for those working in a health system overwhelmed by infected patients. We imagined health care professionals confronted by the terrible dilemma of having to ration medical resources, deciding who should live or die. Fortunately we have largely been spared from that horror we imagined.

However, it would be a mistake to think that the worst of the ethical dilemmas associated with COVID-19 have been avoided. Rather, they have merely been displaced to another arena – the economy, and the world of work, in particular.

The devastation of the Australian economy has already claimed many victims – not least the hundreds of thousands of people who have lost (or are about to lose) their jobs once the JobKeeper ‘safety net’ is removed.

Those who join the unemployment queues or whose business collapse or whose opportunities dry up will pay the highest price for the choices we have made, so far.

However, there will also be a considerable burden borne by those who must make the terrible decisions about who keeps, or loses, their job during an extended recession – and by those who appear to have survived the crisis, seemingly unscathed.

Every organisation in Australia will be affected by COVID-19. A few will have prospered. However, most will be re-evaluating every aspect of their operations. It is our contention that those with the strongest ethical foundations are most likely not only survive the immediate crisis – but will emerge stronger.

This is not to suggest that the process of change will be easy … in fact, it will be incredibly difficult. However, there are three key insights that we believe will not only ‘limit the damage’ but actually set up organisations for a better future.

-

Crises usually bring to light the ‘shadow values’ at work within an organisation: the fewer the better.

Values and principles inescapably shape our choices – and therefore the world they produce. Many organisations enter a situation of crisis with an established set of stated values and principles. However, a crisis can bring into the light an operative set of values and principles that may otherwise dwell in the ‘shadows’.

These ‘shadow’ values and principles often arise as a ‘mutation’ of the stated set. For the most part, the process of mutation is subtle – beginning with an initial act that is at first tolerated (often because it delivers a profitable outcome) and then accepted as ‘normal’. The process of drift is known as the ‘normalisation of deviance’ – and often proceeds without being observed for what it is: a corruption of the norms of the organisation. Occurring in the ‘shadows’ of an organisation’s culture, the mutations are genuinely ‘unseen’ and therefore resistant to correction.

The most common reason for shadow values and principles gaining a foothold during a crisis is that they are ready-made to fill the vacuum caused whenever ethics is reduced to being an ‘optional extra’, or regarded as a luxury that can only be afforded during easier times.

This weakening of commitment to an organisation’s espoused values and principles allows the shadow set to grow in strength.

One of the best examples is that of the German automaker, Volkswagen, where their stated value of ‘excellence’, was mutated into a shadow value of ‘technical excellence’. The resulting decisions led to an emissions scandal that has cost the company a small fortune in fines and severe reputational damage.

Identifying the risk of mutation of the ethical ‘DNA” of an organisation before it occurs, or if this is not possible, having the tools needed to recognise and correct shadow values and principles when they arise will be critical for organisations moving through this next period.

-

Those who ‘survive’ a crisis may suffer the effects of ‘moral injury’ – leading to sub-optimal results for them personally (and their organisation) if the injury is not addressed.

Many people working in business and the professions have already been confronted by the need to make some distressing decisions – not least of which has been to weigh in the balance the good of the organisation versus the livelihood and well-being of employees.

In many cases, the people who lose their jobs will have been loyal and diligent employees who have performed their roles with distinction; roles that are either unaffordable during a recession or that no longer make sense in the emerging strategic environment where the risks posed by the virus are controlled but not eliminated.

Those who make necessary – but unfair – decisions will suffer a certain amount of personal harm from doing so. However, exposure to the risks of such decision making is generally understood to be part of the job. The greater risk is to those people who play no direct part in the decision making but who also feel that they are the inadvertent ‘beneficiaries’ of the sacrifices made by others.

There is much to be learned about this phenomenon by considering the experience of those who survive disasters like shipwreck. The first phase of the disaster will see strangers (and even rivals) driven to work together by the indiscriminate ‘lash of necessity’. People will bend themselves to the task of rowing towards safety – hopeful that a rescuer might be close at hand.

The second phase arises when the situation becomes more desperate … when rations are depleted, when the water is rising toward the gunwales of an overloaded lifeboat. It is then that some place their personal interests before those of all others – throwing overboard any sense of fellow-feeling. Yet, there will be others who decide that they will make the ultimate sacrifice – quietly slipping below the waves so that others survive.

Finally, the moment of rescue comes and the lash is withdrawn. It should be a time of celebration and euphoria. However, it is common for those who survive enter a stage of grief – because they have survived when others, each equally deserving, have not.

‘Moral injury’ is not only experienced by those who made the decision to sacrifice others, or who hoarded goods that could have helped others. The same injury is caused by those who remain without any reason to explain (or justify) their relative good fortune.

Telling any of these people that they should count themselves ‘lucky to have survived’ is worse than useless. Mere survival, as experienced by such people may be a welcome reality – but it is also an ‘empty achievement’ – and does nothing to protect against the consequences of untreated moral injury; which include depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and in the most severe of cases, suicide.

-

The best response to moral injury is to offer the opportunity to find meaning in adversity – a positive reason that justifies continuing effort.

There are only two ways to prevent moral injury. First, one can seek support when making the initial decisions so that, no matter how tough, they do not give rise to a form of regret and self-blame linked to a series of ‘if only’ statements (‘if only I had considered that perspective’, ‘if only I had thought of that option’, ‘if only I had asked one more question’ …).

Second, one can offer a purpose that transcends mere survival. It is only then that the sacrifice of others can be a source of positive motivation. Instead of individuals being beneficiaries, they become ‘stewards’ of a purpose that, if realised, will justify the sacrifices made by others.

Of course, the saving purpose must be something of real substance – not just a few words that make people feel good about themselves. The purpose must be non-trivial, enduring and deep, the kind that people can truly believe in.

However, there is a temporal ‘twist’ at this point. There’s not much point in having a purpose that will rescue an organisation from crisis if decisions made during the crisis render the purpose invalid or unbelievable.

The last thing you want is for those who survive to look back on their experience of crisis and conclude that all that went before makes the purpose seem to be a ‘hoax and the organisation’s leadership a group of hypocrites. That is why it is essential that organisations identify and manage any shadow values or principles that might undermine the better future it must create in the aftermath of the crisis.

In these circumstances, ethics is neither an ‘optional extra’ nor a ‘luxury’. It is a necessity!

The lesson in all of this is relatively simple

Those who wish to prosper in the aftermath of a crisis need to project themselves into the future and identify an underlying purpose that guides their decision making in the present.

Of course, it will be impossible to predict all of the details that define the strategic and tactical environment in which the organisation will need to operate. However, an organisation’s Purpose, Values and Principles (the three principal components of an Ethics Framework) should provide an enduring platform that is serviceable in all environments but one … where there is no genuinely useful role left for the organisation to perform.

Unless that exception exists, organisations and their leaders have an obligation not merely to persist, but to flourish for the sake of all those that made their continued survival possible.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 31 MAY 2020

If you were to plot a timeline of the Covid-19 pandemic, one way of dividing up the different stages would be by reference to the resources shortage we were facing at the time. First stage: toilet paper and hand sanitiser. Second stage: masks and protective equipment. Third stage: ventilators and hospital beds. Fourth stage: money.

Fortunately, we seem to have skipped stage three in Australia, and for the most part, we’ve addressed shortages in protective equipment and at grocery stores. However, with the focus in Australia now largely on the economic fallout from the pandemic, the question of how to distribute and share limited wealth is now at the front of people’s minds.

Among a range of economic measures introduced to address the Covid-19 crisis, the government has suspended insolvent trading laws for six months. This enables organisations who would otherwise go out of business to continue trading.

Welcomed as a lifeline by many, the question we should be asking is: who is the lifeline for? Should every organisation who is eligible take advantage of the scheme? Whilst it would be tempting, and completely understandable for someone to try to take advantage of every possible support before letting their business go, doing so may well overlook other, more pressing concerns.

John Winter, the CEO of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency & Turnaround Association (ARITA), worries that the six-month safety net might have significant economic impacts later on. “All they are doing is kicking the can down the road,” he says. As a number of businesses take no-interest or low-interest loans to mitigate insolvency, they increase the risk of a more expensive insolvency later on.

“You’re going to have a tsunami of insolvency. You have to have one,” says Winter.

Ethicists use the term ‘moral temptation’ to refer to situations where personal needs and desires are strong enough to override our usual ethical decision-making. Moral temptations aren’t ambiguous ethical choices; rather, they’re situations where the potential benefits for a person are high enough that they might rationalise making a choice that doesn’t hold up to their ethical beliefs. The possibility of keeping a business afloat could generate this kind of situation.

What typically occurs in a moral dilemma is that a person puts disproportionate weight on their own needs and desires, thus overlooking or underestimating the importance of what other people need.

When it comes to the decision to continue trading whilst insolvent, this might mean failing to consider how desperately creditors need their outstanding debts paid. It might mean retaining staff and giving them false hope of ongoing employment, rather than giving them redundancies and the opportunity to seek work elsewhere, whilst unemployment payments are higher than usual. In many cases, it’s unlikely someone taking an objective view would think the benefits of keeping a struggling business afloat were justified, relative to the harms it generates for other groups of people.

“When you are insolvent as a business, you know that you’re not going to pay back the money you owe,” says Winter.

“You can’t get more broke than broke, [but] what you are doing is significantly impacting those that you owe money to,” he adds. “If you’re running a small business, it’s generally other small businesses you owe money to as well. You could actually be sending them broke.”

Here, it might be helpful to consider the kinds of questions that ventilator shortages and other health resource limitations are posing around the world – the kind we’ve managed to avoid here. In New York, where there is a real possibility of healthcare shortages, guidelines indicate that doctors “may take someone who is desperately ill and not likely to live off that ventilator and put someone else with a much better chance on.”

The logic here is simple: when faced with a choice between delaying inevitable, imminent death and restoring someone’s health to live a full life, we should choose the latter.

In many cases, families and patients will decide to remove a ventilator in such cases, knowing that in doing so, they are gifting a lifeline to someone else. For some, the choice is also one that offers considerable relief. Rather than fighting to maintain life, despite the suffering on all involved, they can finally let go.

Winter suggests a similar relief is possible for those whose businesses are in trouble. “When directors finally sit down and say, ‘yeah, I’m done, I’m handing the business over to a liquidator’, they feel a massive sense of relief. They’ve taken so much weight on their shoulders because of the ethical concerns they face around the consequences for others.”

For organisations on the brink of insolvency, the central question seems to be whether to take a lifeline or be a lifeline – resolving matters as best they can, ensuring staff and creditors are cared for – or taking a shot at reviving their business with the help provided?

Before making a choice, organisations facing insolvent trading may wish to consider:

- Do I have justifiable reasons to think that the business will be in a better financial position? Will it be able to pay its debt and meet its obligations in six months time?

- What effects would my decision to continue trading have, whether I am successful or not, on creditors and staff?

- What is the intended purpose behind the suspension? Am I exploiting a loophole or one of the intended beneficiary?

- Are there people who could be saved if I decided to cease trading now? Does the business have any obligations toward those people?

- Is my desire to see this business continue clouding my judgement? Do I need someone independent to help me make this decision?

There is no hard-and-fast rule here. Some organisations will be able to use this support to revive their business to a healthy state. Ideally, those that do have done so in the confidence that the risks they were posing to others were low: they weren’t ‘taking a punt’ with the time available, but making an informed choice about what was in the best interests of the business, creditors, staff and the economy at large.

There is an old saying in military circles: death before dishonour. The question facing some organisations now is just that: when are the social costs too high for me to continue trading? When is it the right thing to do to pull the plug?

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why businesses need to have difficult conversations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Reports

Business + Leadership

Managing Culture: A Good Practice Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

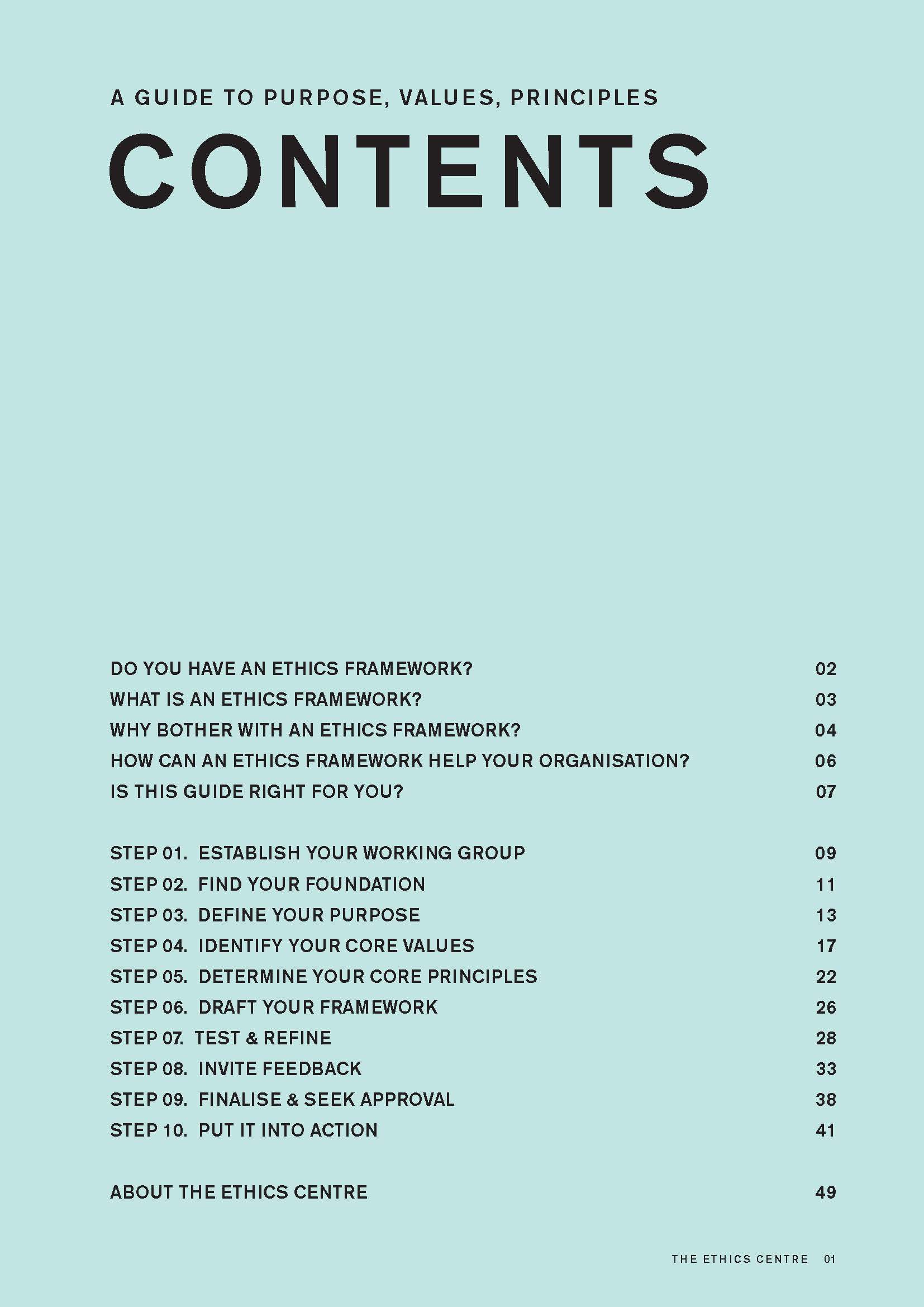

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

Purpose, Values, Principles: Ethics Framework Guide

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

Each day, countless decisions are made within organisations of all shapes and sizes. An Ethics Framework provides a compass for those choices.

A solid Ethics Framework offers a clear statement of what an organisation believes in and what standards it applies. It’s a roadmap for good decisions, and if it’s lived throughout an organisation, it’s also a guide to making that organisation the best version of itself.

Fundamental to good business, every organisation should have an Ethics Framework to guide decision making; from Apple, Amazon and ANZ, to the Nedlands Netball Association.

"An Ethics Framework is foundational. It provides the blueprint for organisational decision making, delivering clarity, consistency and connection across all levels and responsibilities."

WHATS INSIDE?

Learn what an ethics framework is

Why you need an ethics framework

A step by step process to establish your own

Tools to embed your framework

Whats inside the guide?

AUTHORS

Authors

Dr Matt Beard

is a moral philosopher with an academic background in applied and military ethics. He has taught philosophy and ethics at university for several years, during which time he has been published widely in academic journals, book chapters and spoken at national and international conferences. Matt’s has advised the Australian Army on military ethics including technology design. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement, recognising his “prolific contribution to public philosophy”. He regularly appears on television, radio, online and in print.

Dr Simon Longstaff

has been Executive Director of The Ethics Centre for over 25 years, working across business, government and society. He has a PhD in philosophy from Cambridge University, is a Fellow of CPA Australia and of the Royal Society of NSW, and in June 2016 was appointed an Honorary Professor at ANU – based at the National Centre for Indigenous Studies. Simon co-founded the Festival of Dangerous Ideas and played a pivotal role in establishing both the industry-led Banking and Finance Oath and ethics classes in primary schools. He was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2013.

DOWNLOAD A COPY

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

A new guide for SME's to connect with purpose

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 27 MAY 2020

Purpose, values and principles are the bedrock of every thriving organisation. With many facing a reset right now, we’ve released a guide to help small to medium sized businesses create a road map for good decisions and robust culture.

In the world of architecture, even the most magnificent building is only as strong as its foundations. The same can be said for organisations. In these times of constant change, a strong ethical culture is essential to achieving superior, long-term performance – driving behaviour, innovation, and every decision from hiring, through to partnerships and customer service.

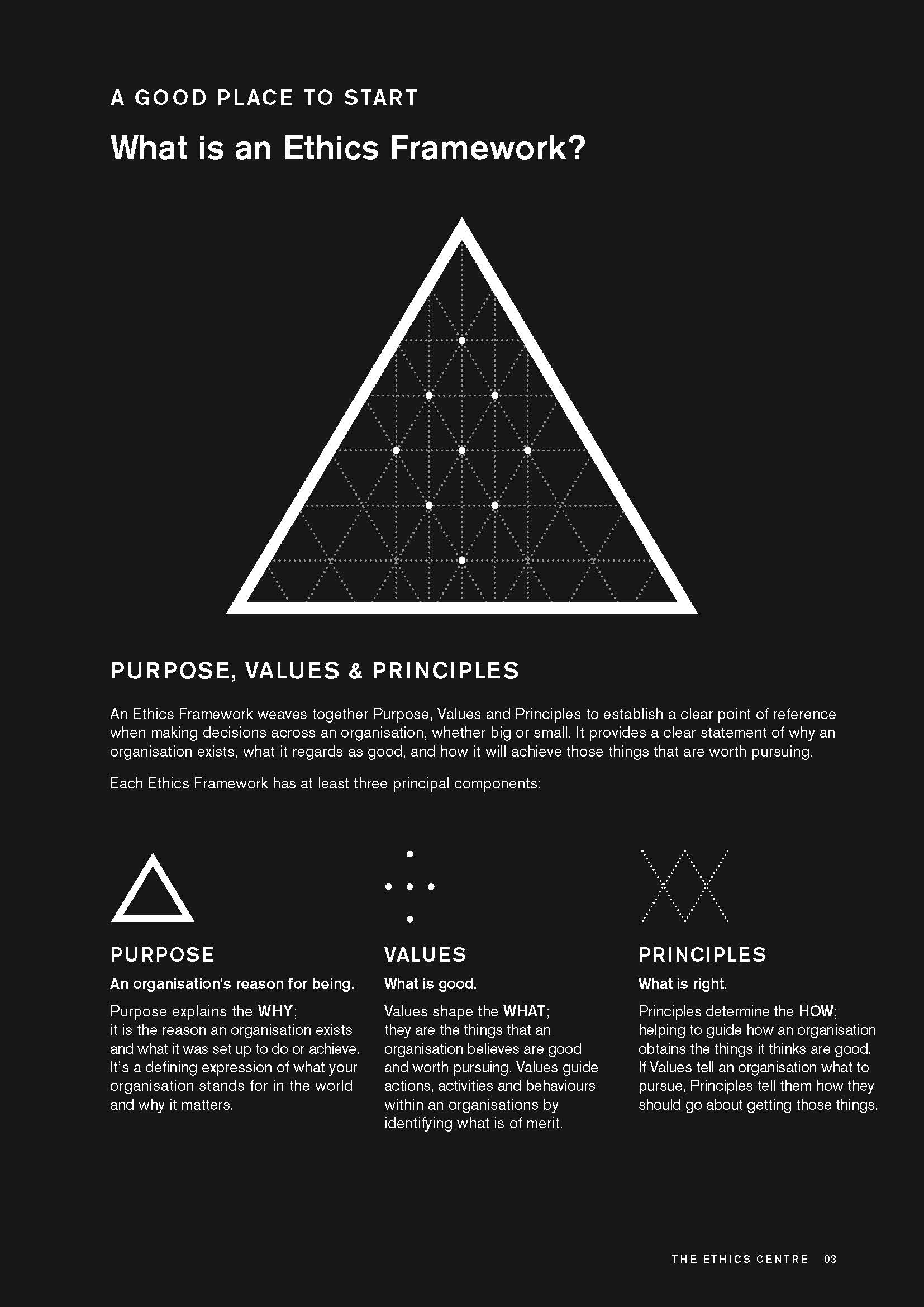

The foundations for a high-performance culture are made up of three principal components: Purpose, Values and Principles.

Each is necessary. Each plays a specific role. Each complements the other to make a stable foundation for the whole. Together, they make up what we call an Ethics Framework.

PURPOSE (WHY) – An organisation’s reason for being.

Purpose explains the WHY; it is the reason an organisation exists and what it was set up to do or achieve. It’s a defining expression of what your organisation stands for in the world and why it matters.

VALUES (WHAT) – What is good.

Values shape the WHAT; they are the things that an organisation believes are good and worth pursuing. Values guide actions, activities and behaviours within an organisations by identifying what is of merit.

PRINCIPLES (HOW) – What is right.

Principles determine the HOW; helping to guide how an organisation obtains the things it thinks are good. If Values tell an organisation what to pursue, Principles tell them how they should go about getting those things.

The Ethics Centre has spent the past thirty years helping organisations to build and strengthen their ethical foundations. In many cases, we have been able to work directly with organisations. However, not every organisation has either the time or the funds needed to invest in specialist advice.

So, the Centre was pleased to accept a grant from The Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s Community Benefit Fund for the purpose of creating a ‘DIY Guide’ for ethics frameworks – with a special focus on the needs of small to medium-sized businesses. It goes beyond broad theory to offer practical, step-by-step guidance to anyone wanting to define and apply their own Purpose, Values and Principles.

The publication of this guide comes at an especially important time. The current pandemic is testing organisations as never before.

Indeed, COVID-19 is every bit as dangerous as an earthquake – except, in this case, it is the ethical foundations of organisations that will determine whether they stand or fall. In a time of crisis, weak foundations are susceptible to crumble, opening up an organisation to the risk it will make ‘bad’ decisions that will ultimately cost it dearly.

The Ethics Centre believes that prevention is better than cure. Our hope is that the practical guidance offered by this guide will provide owners and managers with the tools they need to build stronger, better businesses.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 19 MAY 2020

If multinational tech platforms paid more tax on the revenues they made in Australia, would they be in a better moral position to resist government attempts to force them to pay a ‘license fee’ to news media?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

There are a couple of ways to look at this question – one as a matter of principle, the other through the lens of prudence. In terms of principle, I think that we should treat separately the issues of tax and the proposed ‘licence fee’. This is because each issue rests on its own distinct ethical foundations.

In the case of tax, all citizens (including corporate citizens) have an obligation to contribute to the cost of funding the public goods provided by the state. For example, a company like Google shares in the benefits of a society that is healthy, well educated, peaceful and effectively governed under the rule of law. All who draw on and benefit from such public goods should contribute to the cost of their generation and maintenance.

Instinctively, most citizens believe that we should each pay our ‘fair share’ of tax. However, that belief is at odds with the fact that our formal obligation is not to pay a fair amount of tax but, instead, to pay only the amount of tax due to be paid as defined by law. Most of us don’t have much choice about how we discharge this formal obligation – as our taxes are automatically remitted to the Australian taxation Office (ATO) by our employers.

However, most corporations, including Google, have considerable latitude when calculating the tax they think due. For example, corporations have a clear choice about the extent to which they move right to the edge of what the law allows: ‘avoiding’ (which is legal) but not ‘evading’ (which is illegal) tax obligations that, to an ordinary person, might seem to be due.

It is this approach to ‘tax planning’ that allows Google to earn revenue, in Australia, of $4.3B yet only pay tax of $100M. Google has a perfectly rational argument about how this can the case – and relies on the fact that it should only pay tax that is legally due.

However, as is the case with other multinational corporations who make similar calculations, Google’s position fails the ‘pub test’ in that it seems to be unfair? Why? Because it seems inherently improbable (and improper) that such massive local revenue should flow offshore to benefit people who contribute nothing to maintain the society that has made possible such a financial windfall.

The issue of Google paying a ‘licence fee’ to the creators of news content is somewhat different. In general, you’d think it a reasonable expectation that a company pay for the inputs it draws on to make a profit. After all, businesses pay for labour inputs (wages), for financial inputs (interest and dividends), for material inputs (cash outlays), etc. So, why not pay for content that is derived from other sources?

Of course, what’s good for the ‘goose’ should be good for the ‘gander’. Companies like News Corporation and Nine should also be asked if they pay for all of the inputs that they draw on to make a profit? For example, do they pay for all published opinion pieces, or for the interviews they conduct, etc.? However, in general, it seems reasonable to expect that Google (and other companies) should pay for what they derive from others.

Of course, Google does not agree – and is especially opposed to Australian proposals because, if adopted, they will set a precedent that other countries are likely to follow. It is this consideration that leads us to look at the issue through the lens of prudence.

Governments (of all political hues) are especially attentive to the demands of the media. What NewsCorp and Co. want, they usually get … unless opposed by the one force that wields even greater influence over the judgement of politicians – the force of public opinion. So, if Google wishes to prevent or limit the levying of a ‘licence fee’, its most potent ally might have been the Australian public.

However, the electorate is unlikely to back the interests of a company that is perceived not to back the interests of the people whose taxes provide the infrastructure on which Google depends for the enrichment of its overseas owners.

This is where principle and prudence align. Google (and other multinational corporations) should pay taxes that amount to a fair contribution to the maintenance of public goods. Had it done so, then Google might have many more friends who might stand beside it in its battle with other powerful corporations like NewsCorp and Nine.

I am not sure if arguments from principle or prudence will really carry much weight. Perhaps the situation needs to be expressed in the language of financial self-interest. Compared to a licence fee (which might be as high as $1B per annum), would a less aggressive approach tax planning have have been a good investment?

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are we ready for the world to come?

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 15 MAY 2020

We are on the cusp of civilisational change driven by powerful new technologies – most notably in the areas of biotech, robotics and expert AI. The days of mass employment are soon to be over.

While there will always be work for some – and that work is likely to be extremely satisfying – there are whole swathes of the current economy where it will make increasingly little sense to employ humans. Those affected range from miners to pathologists: a cross-section of ‘blue collar’ and ‘white collar’ workers, alike in their experience of displacement.

Some people think this is a far too pessimistic view of the future. They point to a long history of technological innovation that has always led to the creation of new and better jobs – albeit after a period of adjustment.

This time, I believe, will be different. In the past, machines only ever improved as a consequence of human innovation. Not so today. Machines are now able to acquire new skills at a rate that is far faster than any human being. They are developing the capacity for self-monitoring, self-repair and self-improvement. As such, they have a latent ability to expand their reach into new niches.

This doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Working twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week in environments that no human being could tolerate, machines may liberate the latent dreams of humanity to be free from drudgery, exploitation and danger.

However, society’s ability to harvest the benefits of these new technologies crucially depends on planning and managing a just and orderly transition. In particular, we need to ensure that the benefits and burdens of innovation are equitably distributed. Otherwise, all of the benefits of technological innovation could be lost to the complaints of those who feel marginalised or abandoned. On that, history offers some chilling lessons for those willing to learn – especially when those displaced include representatives of the middle class.

COVID-19 has given us a taste of what an unjust and disorderly transition could look like. In the earliest days of the ‘lockdown’ – before governments began to put in place stabilising policy settings such as the JobKeeper payment – we all witnessed the burgeoning lines of the unemployed and wondered if we might be next.

As the immediate crisis begins to ease, Australian governments have begun to think about how to get things back to normal. Their rhetoric focuses on a ‘business-led’ return to prosperity in which everyone returns to work and economic growth funds the repayment of debts accumulated during the the pandemic.

Attempting to recreate the past is a missed opportunity at best, and an act of folly at worst. After all, why recreate the settings of the past if a radically different future is just a few years away?

In these circumstances, let’s use the disruption caused by COVID-19 to spur deeper reflection, to reorganise our society for a future very different from the pre-pandemic past. Let’s learn from earlier societies in which meaning and identity were not linked to having a job.

What kind of social, political and economic arrangements will we need to manage in a world where basic goods and services are provided by machines? Is it time to consider introducing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) for all citizens? If so, how would this be paid for?

If taxes cannot be derived from the wages of employees, where will they be found? Should governments tax the means of production? Should they require business to pay for its use of the social and natural capital (the commons) that they consume in generating private profits?

These are just a few of the most obvious questions we need to explore. I do not propose to try to answer them here, but rather, prompt a deeper and wider debate than might otherwise occur.

Old certainties are being replaced with new possibilities. This is to be welcomed. However, I think that we are only contemplating the ‘tip’ of the policy iceberg when it comes to our future. COVID-19 has given us a glimpse of the world to come. Let’s not look away.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 13 MAY 2020

My employer sent me a questionnaire designed to test if my home working environment meets basic standards. If I’d answered truthfully I would have ‘failed the test’. But what’s the point in telling the truth when I have to work at home in any case? Was it wrong to lie on the form?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

Although this ethical issue seems to fall on you – as the person receiving the survey – it actually starts with your employer’s decision to request this information in the first place. I assume they did so in order to meet their legal obligations … and perhaps conditions set by their insurer, etc.

However, the process they activated was not designed to cope with circumstances like the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the occupational health and safety checks they are trying to use were developed for a time when working from home was the exception – rather than the rule.

Back then, it made excellent sense to check that those opting to work from home could do so with good lighting, an ergonomic chair … and all the other requirements one would reasonably expect to find in a safe, modern office environment.

However, for the time being, millions of people have no choice but to plonk themselves down a couch or at a kitchen table or … wherever … to work as best they can.

So, let’s imagine that your home environment is not especially suited for work? Suppose you pass on this information to your employer. Do we really think that they would rush over with a well-designed desk, chair, light, etc.?

Perhaps some might do so … but in the current circumstances I doubt that this would be the response. Even if one sets aside questions of cost – are there enough new chairs, desks, computers, etc. to make good the likely deficiencies in the working arrangements of a large percentage of the active workforce? I suspect not.

Given this, I imagine that many people have decided to collude (with their employer) in a ‘white lie’. Both sides know (but will not say) that to offer an honest response would probably be an exercise in futility.

With this in mind, ‘form’ triumphs over ‘substance’ – with employees signing off on a declaration that they know not to be strictly true – but that is practically required all the same.

Now, I know that thus might seem to be a fairly minor form of deception – something to be excused because deemed to be ‘necessary’. However, I reckon that it is never a good thing to lie – and that those who plead ‘necessity’ must first do everything they can to prevent this kind of dilemma from arising in the first place.

This is because even occasional acts of dishonesty can start to warp a culture because they suggest that core values and principles can be abandoned whenever the going gets tough.

In summary: I think it was wrong to lie on the form (even if understandable). However, it would have been far better – for all – if your employer had not put you in this invidious position in the first place.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Let the sunshine in: The pitfalls of radical transparency

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

Emerging from the turbulence of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to escape the hold of our past and use moral imagination to explore a better future.

After months of living through disruption, old work habits and perceptions may no longer fit the ‘new normal’, says Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School.

“There’s a very positive side to this, because it makes us realise that the seemingly obvious, natural way of operating is not so obvious anymore.” says Baur.

“It does afford us the ability to think a little bit more carefully about what we’re doing.”

A simple example may be that, after mastering virtual meetings, we realise that the regular face-to-face interstate meetings we thought to be essential are not, in fact, a necessary part of doing business. Instead of asking ‘can we do this online?’ we might now ask, ‘should we do this online, is there a good reason to do it in person?’

“It’s liberating, potentially, to be able to be thrown back and see that the seemingly natural is really not so natural and obvious after all,” says Baur.

Aspects of life previously unquestioned, such as our choices of where to live, send our kids to school or even the jobs we do, may be cast in a different light.

Speaking with Bob McCarthy, an Irish colleague, he spoke of the experience of the ‘Celtic Tigers’ during ten-year-plus period of economic growth prior to 2008. “Ireland had never experienced anything like it and our economy became the envy of the world. Of course, we lived in accordance with our new wealth and fame – two houses each, BMWs, ski holidays and buying chalets in Morzine”, says McCarthy.

Many rationalised their good fortune – ‘we’ve had it tough for so long we deserve a little luxury.’ So, when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) crash came, it came hard. There was a 60% average fall in property prices, high unemployment, many family tragedies, house repossessions and years of debt to repay.

Bob said that the experience of crisis changed attitudes and behaviours, “Now, those of us who have been through this look at life, business, money, relationships, values, ethics through a different filter than before”.

He describes the experience of having benefitted from the pain. What had once seemed important during the times of excess are no longer important. What didn’t matter then, matters to him now. “Don’t get me wrong – not everything has changed. But for most the filter we use has changed”.

Baur says that, with the experience of COVID-19, we now have a similar opportunity to reset our aspirations, “When we were riding easy, just several weeks ago, we were in a state of deception.” He recognises that the pandemic has caused major economic shocks – perhaps even more severe than those caused by the GFC, “And now we can regroup. That seems to me a more positive, healthy way of thinking of it – that all of this wealth and expectation was not really ours to have to begin with.”

Bigger is not always better

The aftermath of the pandemic presents a good time to reassess our attitude to growth. The fact that almost all sectors of business have suffered means that there is a collective opportunity to slow down and reassess whether the purpose of business is to make more money for money’s sake, or to provide for human need.

Business is now attending to issues that were always there to be addressed – but remained largely ‘unseen’. By presenting itself as a ‘common enemy’, COVID-19 has caused us all to look up at the same time and respond to a suite of collective problems.

In many cases, our response has been an expression of human goodness, compassion and altruism. ‘Them’ has become ‘us’.

For example, Accor hotels, is opening up unused accommodation to support vulnerable people. Simon McGrath, Accor’s CEO, says, “Our doors are open,” said Accor’s McGrath “We have accommodation assets that can help people in times of need, and while the industry’s been devastated commercially, it doesn’t mean we can’t help.”

In a similar vein, UBER has partnered with the Women’s Services Network to provide 3,000 free rides to support those needing safe travel to or from shelters and domestic violence support services.

Australia was relatively unscathed by the GFC of 2008 and did not experience the large economic downturn felt elsewhere on the globe. Australia has also managed to flatten the curve and “none have been more successful than Australia and New Zealand at containing the coronavirus,” said Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

This is thanks to our strong public health system and our comprehensive testing regime, to the tracing of carriers and our strict self-isolation and physical distancing laws. We were also lucky that our geographic isolation bought us an extra 10 precious days to prepare.

However, Australia has not and will not escape the economic consequences of the pandemic – and our response to the threat it poses. So, how will we shape up when the challenge is an economic recession as opposed to a medical emergency? Will the good will and sense of common endeavour persist during the next phase of struggle? More interestingly still, will the sense of mutual obligation survive a return to posterity? Or will we resume our ‘old ways’?

Baur says an argument could be made that business and society in general did not make the most of the lessons to be learned from the GFC, more than a decade ago. Ireland’s Bob McCarthy, is of the same opinion, “We may be having an opportunity that would have been a lost opportunity from that time,” he says.

“What might be seen as a loss of opportunity, a loss of growth, in one limited respect, is really a darn good thing for everybody,” Baur says.

Echoing the same sentiment, Mike Bennetts CEO of Z Energy in New Zealand told audiences at the Trans – Tasman Business Circle that this virus has accelerated us into the future by 5 years, so “let’s make the most of it”. Our instinct is to seek comfort and confidence in the known which will mean going back to the way it was.

The challenge, now, is not only to create a new future but a better future. For that to happen we need to unleash a better version of ourselves.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Ethical Infrastructure

Explainer, READ

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Moral hazards

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Leading ethically in a crisis

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

It is difficult to excel in the art of leadership at any time – let alone in the midst of a crisis. Yet, this is precisely when good leadership is at a premium.

Right now, we must ask: what is ‘good’ leadership and how should leaders respond to the demands placed upon them during periods of extraordinary ethical complexity?

In attempting to answer these questions, I am thrown back on my own experience of leadership – including at present. In that sense, this not a detached, objective account. Rather, it is a reflection on (and of) lived experience.

The first obligation of a leader is to see, and sense, the whole picture. This means being alive to the undercurrents of feeling and emotion flowing through the organisation, while simultaneously keeping a clear view of the evolving strategic landscape and being ‘present’ in the moment.

The good leader needs to ensure that no one affected by the crisis is either overlooked or marginalised. This is harder than it seems. When driven by the ‘lash of necessity’, it’s all too easy to favour some people because of their utility, while dismissing others as ‘dead weight’.

I have been struck by the number of times that people have said the current emergency requires them, albeit reluctantly, to be cold-hearted, brutal or even cruel. I realise that such comments do not reflect their personal inclination – but instead reflect their response to evident necessity. However, I think that ethical leaders have an obligation to challenge that tendency – not least by naming it for what it is.

This is not to say that issues of relative utility are unimportant. Nor is it the case that one should avoid difficult decisions – such as those that might lead to job losses. Rather, the leader’s job is to ensure that such decisions are not made on the basis of cold, dispassionate calculation. Instead, the leader has an obligation to ensure that the ethical weight of each decision is felt and the heft of the burden that falls from each decision is known.

The second requirement of ethical leaders is that they resist demands for a certainty they cannot or should not provide. This is easier said than done. There are some contexts in which the suspense of ‘not knowing’ can be thrilling; however, for most people operating under stress, confronting ‘the unknown’ reinforces a sense of powerlessness and is deeply unsettling.

Even so, ethical leaders should resist the temptation to offer people false certainty, no matter how much that might be desired. Instead, a good leader should be resolutely trustworthy by only claiming as ‘certain knowledge’ what is genuinely known. Otherwise, a leader’s integrity can be undermined by something as simple as a gap between what was asserted as fact and what is subsequently revealed to be true.

None of this is to suggest that people be denied glimmers of hope based on one’s best estimate. It is merely to counsel caution – especially when a delay can open up new possibilities. The recent and unexpected emergence of the Federal Government’s JobKeeper scheme is a good example.

Leading during a crisis requires an ability to foresee a future, preferred state and then ‘backcast’ to the present when making decisions. As noted above, in the course of a crisis, many decisions will be made under the ‘lash of necessity’.

In these circumstances, people will be driven to accept the harshest treatment as a ‘necessary evil’. However, a time will come when the crisis is relegated to the past and those who remain in an organisation will want to know what justified the sacrifice – especially that made by those who fell along the way.

Telling people that it was ‘necessary’ will not be enough. Instead, those who remain will require a positive justification that goes beyond ‘mere survival’. It is in the light of that positive justification that all of the preceding decisions need to be evaluated. So, leaders need to ask themselves, ‘is today’s decision going to foreclose on the future we hope to create’. In particular, will my present choice make my preferred future impossible? Will it delegitimise my future leadership?

Finally, leaders need to release themselves from the unrealistic expectation of ‘ethical perfection’. This is not to say that one should be careless in decision making. Rather, it is to recognise a fundamental truth of philosophy: that some ethical dilemmas are so perfectly balanced as to be, in principle, undecidable.

Yet, we must decide. The only reasonable standard to apply in such cases is that we are sincere in our judgement and competent in our capacity to make ethical decisions – a skill that can be learned and supported.

There are particular ethical challenges to be faced by leaders during times such as these. Critical decisions may have to be made alone. Not everything that could be said should be said. There are some options that need to be considered but not voiced – as they would cause unnecessary worry – only to remain dormant.

There are ‘gordian knots’ that may need to be cut rather than carefully unravelled over a period of time that is simply not available. There is the fact that the weaknesses in oneself (and others) will be revealed under pressure – and that unpleasant truths will need to be acknowledged and endured.

At times such as these, the things that sustain good leaders are an unshakeable sense of purpose and a solid core of personal integrity. One might protect others from the harshest of possibilities for as long as possible – but never oneself.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Reports

Business + Leadership

Managing Culture: A Good Practice Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How BlueRock uses culture to attract top talent

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moving work online

Moving work online

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Talya Wiseman The Ethics Centre 10 APR 2020

As the COVID-19 dominos continue to fall, many organisations are scrambling to rethink the way they work. These changes are happening in real time; on a scale both unprecedented and unpredicted.

The last pandemic of this nature, the Spanish Flu, occurred 100 years ago – well before anyone had dreamed up the internet, computers and video conferencing. In 2020, advances in technology, such as international flights, have allowed this virus to spread at a much faster rate. However, they have also afforded many organisations the opportunity to pivot their operations online.

Schools and universities have, for the most part, managed this at an incredibly fast pace. With barely any notice, teachers have become adept at using online delivery platforms and are coming up with new ways to engage their students online.

Students are able to continue their same classes via platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams; all the while knowing that the rest of their class is right there, learning alongside them.

Now that all but essential workers are urged to stay at home, ideas about working environments have also been forced to alter at an unusually rapid pace. For example, workplaces and teams have begun to adapt to meeting online. A popular meme doing the rounds at the moment depicts a scenario 40 years from now when a grandchild asks their grandparent with wonder “Go to work? You used to actually GO to work?”

It is incredible to see how many fundamental changes and shifts in thinking have occurred in such a short space of time. We simply had neither the time nor the opportunity to incorporate long policy discussions, carefully timed rollout plans or trial periods. Many organisations that previously assumed they needed a common workplace are now questioning the validity of this assumption.

What happens next?

The big question is this: when all of this is over and we return to normal, what will normal look like? Will organisations revert to their old ways? Or will we have seen the value in new patterns of working? Our eyes have been opened through this experience. Our assumptions about the nature of work have been challenged. Having reorientated towards online workplaces, will it be so easy to pivot back? And will we want to?

There are certainly benefits to workplaces accepting remote working as a viable option. Parents and carers, who previously struggled to convince their employers that they could effectively work from home, will likely find this argument much easier to make. If people have been able to fulfill their work duties in these most trying times, clearly it will be easier for them to continue to do so when it is an option they are choosing.

The stigma of working from home has rapidly been removed. It should no longer be seen as the ‘lesser’ option compared to attending an office. Organisations are finding innovative ways to ensure staff feel supported while working from home; while also maintaining expectations of staff – wherever they happen to be located.

The role of the physical workplace

However, there is a risk in realising just how easy it is to do things online. The role that work plays for individuals is much more than just providing an income. Work is also about fulfilment; it is about social interaction. The best initiatives can arise from bouncing ideas around with colleagues. Families can laugh together at the dinner table when sharing work stories and funny moments that occurred at the office. Colleagues can celebrate each other’s success and commiserate together when things don’t go as planned. Work is about so much more than ‘work.’

One of our principles, here at The Ethics Centre, is to “know your world and know yourself”. We believe in the importance of questioning who we are and being conscious of what we do. If the nature of work is fundamentally to change, we must recognise what we are giving up, as well as the opportunities that may arise. Just because we were rushed into this new reality doesn’t mean we can’t carefully consider the best way to move on from it.

Let’s not just fall back into old patterns. Let’s use this as an opportunity for questioning and for finding a better ‘normal’. That might well be a workplace that embraces flexible arrangements and is open to non-traditional office environments, while at the same time never losing touch with deeply human moments and interactions.

Perhaps we will realise that work, regardless of industry, is about purpose, fulfilment and human interaction.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Are diversity and inclusion the bedrock of a sound culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture