In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 JUN 2020

Is there any polite or moderate way to condemn racism? I think not. Nor should there be. As the world has witnessed, on countless occasions, racism kills. It does so for the worst of all possible reasons – by denying the equal humanity of some people simply because of the colour of their skin.

The evil caused by racism is not ‘theoretical’. We do not need to speculate about the horrors that it has unleashed. We have only to listen to the evidence of the enslaved, the dispossessed and the murdered to know what follows when one group of people is thought to be ‘less fully human’ than another.

Some people are upset by the words ‘Black Lives Matter’. They assert an alternative proposition that, ‘All Lives Matter’. Well, of course they do. But that has never been denied by the BLM movement. BLM does not claim that only black lives matter. They do not say that black lives matter more than any other.

They simply state that black lives also matter – in a way that racism denies. And they are right. They might also ask, ‘where were the people chanting ‘All Lives Matter’ when the ‘original sin’ of racism was being visited on the world?’. Why has the ‘All Lives Matter’ brigade only found its voice now that the spotlight has been turned on the oppressors by the oppressed?

I come from a privileged background. So, I can barely imagine what it must be like to be on the wrong end of the racist scourge. I can only guess at my reaction – probably a burning rage at the sheer injustice of my treatment. Like the Rev’d. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr – I would demand to be judged for the quality of my character rather than the colour of my skin. Denied that right, I would let loose my rage on an unjust world and those who represent the system that denied me the most basic form of dignity.

So, it eclipses all understanding to find that, in my experience, the vast majority of Indigenous Australians who have experienced racism are, in fact, amongst the most generous and accepting of people. Yes, there are angry firebrands. However, rather than replicate the wrongs they have suffered or become like those who have denied their humanity, most of those affected choose to repudiate racism by accepting others for who they are and not how they seem.

I speak of this from direct experience. A few days after my seventeenth birthday, I arrived on Groote Eylandt – the home of the Anindilyakwa people of East Arnhem Land and the Gulf of Carpentaria. This was the mid-1970s and the racism directed towards the local mob was common, open and shameless. I doubt that those involved would consider themselves as deliberately being racist. If anything, their racism was almost ‘casual’ in character – a product of ignorance, prejudice and ingrained habits of mind.

It’s hard to explain exactly how and why my experience was so different – perhaps it was my young age or a lucky accident … I really do not know. Whatever the reasons, a few of the Aboriginal men took me under their wing. Friendships developed and eventually I was given a skin name and inducted into a network of kinship ties that I value to this day. The point is that if you were to meet me ‘in the flesh’ you would simply see a middle-aged, white male. As far as I know, I have no genetic ties to the people of Groote. Yet, their acceptance of me has been complete and unconditional.

I have often questioned my experience – wondering if I might have invented a narrative to match an idealized version of myself. However, improbable as it might seem, the connections are real. I will never forget spending an evening with two members of the Amagula Clan (a brother and sister) who explained their kinship connection to me (I carry a Lalara name). Eventually, they simply placed their hands over my heart – to tell me that the colour of my skin, my ‘outward form’, did not matter. That this is not what they saw when they looked at me … but something altogether different. Both are dead – dying far earlier than would have been the case if Australia had been settled on more just terms.

My experience is not unique. Indeed, I believe that our First Nations people are willing to embrace anyone who cares to be open to their doing so. All that is asked is that there be a recognition of simple truths about our relationship to each other and to all that belongs to and is part of the country of which we form equal parts.

In the face of such generosity of spirit – how can we possibly allow racism to persist?

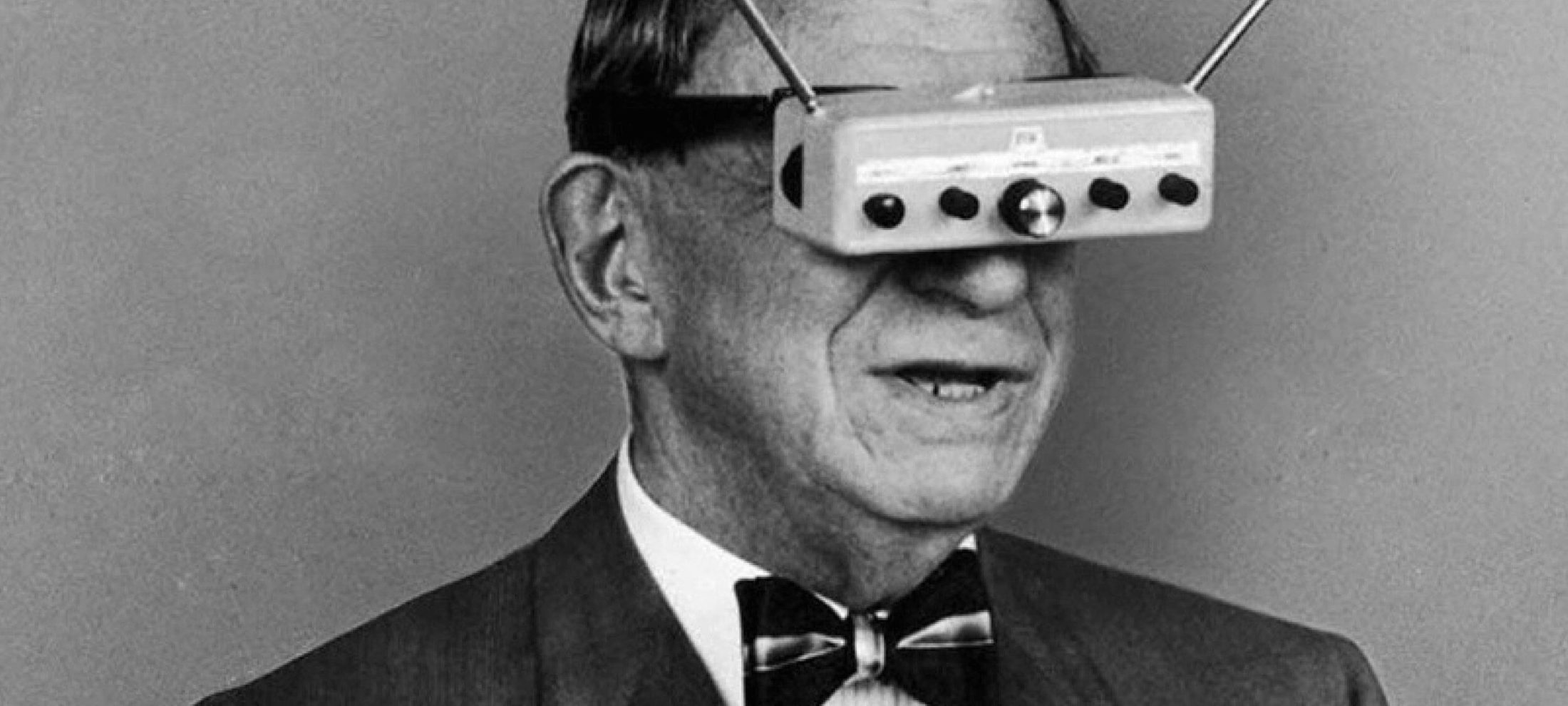

IMAGE CREDIT: The image displayed in this article is a painting by Alfred Lalara (deceased), a talented Groote Eylandt artist. The title is Angurugu River.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Feeling our way through tragedy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The ethics of tearing down monuments

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 JUN 2020

In the UK and US and other nations around the world, public monuments dedicated to people who have profited from or perpetuated slavery and racism are being torn down by demonstrators and public authorities who sympathise with the justice of their cause.

Statues of Christopher Columbus, Edward Colston, King Leopold II and Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee are amongst those toppled in protest.

What are we to make of these acts? In particular, who should decide the fate of such monuments – and according to what criteria?

By their very nature, statues are intended to honour those they depict. They elevate both the likeness and the reputation of their subject – conferring a kind of immortality denied to those of us who simply fade away in both form and memory.

So, the decision to raise a statue in a public place is a serious matter. The choice reveals much about the ethical sensibilities of those who commission the work. Such a work is a public declaration that a particular person, through their character and deeds, is deserving of public commemoration.

There are six criteria that should be used to evaluate the public standing of a particular life. These can be applied at the time of commissioning a monument or retrospectively when determining if such a commemoration is justified.

-

They must not be associated with any gateway acts

Are there aspects of the person’s conduct that are so heinous as to rule them out, irrespective of any other achievement that might merit celebration? For example, one would not honour a genocidal mass murderer, even if the rest of their life was marked by the most profoundly positive achievements. There are some deeds that are so wrong as to be beyond rectification.

-

Their achievements must be exceptionally noteworthy

Did they significantly exceed the achievements of others in relevantly similar circumstances? For example, we should note that most statues recognise the achievements of people who were born into conditions of relative privilege. The outstanding achievements of the marginalised and oppressed are, for the most part, barely noticed, let alone celebrated.

-

Their work must have served the public good

Did the person pursue ends that were noble and directed to the public good? For example, was the person driven by greed and a desire for personal enrichment – but just happened to increase the common good along the way?

-

The means by which they achieved their work must be ethical

Were the means employed by the person ethically acceptable? For example, did the person benefit some by denying the intrinsic dignity of others (through enslavement, etc)?

-

They must be the principal driver of the outcomes associated with their deeds

Is the person responsible for the good and evil that flowed from their deeds? Are they a principal driver of change? Or have others taken their ideas and work and used them for good or ill? It is important that we neither praise nor blame people for outcomes that they would never have intended but were the inadvertent product of their work. In those cases, we should not gloss over the truth of what happened. But if they otherwise deserve to be honoured for their achievements, then these should not be deemed ‘tainted’ by the deeds of others.

-

The monument must contribute positively to the public commons

Would the creation of the monument be a positive contribution to the public commons, or is it likely to become a site of unproductive strife and dissension? In considering this, does the statue perform a role beyond celebrating a particular person and their life? Is it emblematic of some deeper truth in history that should be acknowledged and debated? Not every public monument should be a source of joy and consensus. Some play a useful role if they prompt debate and even remorse.

It will be noted that five of the six criteria relate to the life of the individual who is commemorated. Only the sixth criterion looks beyond the person to the wider good of society. However, this is an important consideration given that we are thinking, here, specifically about statues displayed in public places.

The retrospective application of this criteria is precisely what is happening ‘on the streets’ at the moment. The trouble is that the popular response is often more visceral than considered – and this sparks deeper concerns amongst citizens who are ready to embrace change … but only if it is principled and orderly.

Of course, asking frustrated and angry people to be ‘principled and orderly’ in their response to oppression is unlikely to produce a positive response. That’s why I think it important for civic authorities to take responsibility for addressing such questions, and to do so proactively.

This was recently demonstrated by the Borough of Tower Hamlets that removed the statue of slave owner Robert Milligan from its plinth at West India Quay in London’s Docklands. As the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, noted: “it’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade – but this does not have to be celebrated in our public spaces”.

UPDATE: The statue of slave trader Robert Milligan has now been removed from West India Quay.

It’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade – but this does not have to be celebrated in our public spaces. #BlackLivesMatterpic.twitter.com/ca98capgnQ

— Sadiq Khan (@SadiqKhan) June 9, 2020

What does all of this mean for Australia? There will be considerable debate about what statues should be removed. I will leave it to others to apply the criteria outlined above. However, the issue is not just about the statues we take down.

What of those we fail to erect? Who have we failed to honour? For example, have we missed an opportunity to recognise people like Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy whose resistance to European occupation was every bit as heroic as that of the British Queen Boudica. Two warrior-leaders – the latter celebrated; the other not. The absence is eloquent.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Cancel Culture

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 31 MAY 2020

Having navigated the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic with a relatively low loss of life, Australians are hoping to return to a more familiar pattern of living.

For many of those Australians, they seek an illusion. The world to which they return will have been fundamentally altered – not by the virus – but by the decisions we have taken in response to its emergence.

At one point, we feared those decisions would be especially difficult for those working in a health system overwhelmed by infected patients. We imagined health care professionals confronted by the terrible dilemma of having to ration medical resources, deciding who should live or die. Fortunately we have largely been spared from that horror we imagined.

However, it would be a mistake to think that the worst of the ethical dilemmas associated with COVID-19 have been avoided. Rather, they have merely been displaced to another arena – the economy, and the world of work, in particular.

The devastation of the Australian economy has already claimed many victims – not least the hundreds of thousands of people who have lost (or are about to lose) their jobs once the JobKeeper ‘safety net’ is removed.

Those who join the unemployment queues or whose business collapse or whose opportunities dry up will pay the highest price for the choices we have made, so far.

However, there will also be a considerable burden borne by those who must make the terrible decisions about who keeps, or loses, their job during an extended recession – and by those who appear to have survived the crisis, seemingly unscathed.

Every organisation in Australia will be affected by COVID-19. A few will have prospered. However, most will be re-evaluating every aspect of their operations. It is our contention that those with the strongest ethical foundations are most likely not only survive the immediate crisis – but will emerge stronger.

This is not to suggest that the process of change will be easy … in fact, it will be incredibly difficult. However, there are three key insights that we believe will not only ‘limit the damage’ but actually set up organisations for a better future.

-

Crises usually bring to light the ‘shadow values’ at work within an organisation: the fewer the better.

Values and principles inescapably shape our choices – and therefore the world they produce. Many organisations enter a situation of crisis with an established set of stated values and principles. However, a crisis can bring into the light an operative set of values and principles that may otherwise dwell in the ‘shadows’.

These ‘shadow’ values and principles often arise as a ‘mutation’ of the stated set. For the most part, the process of mutation is subtle – beginning with an initial act that is at first tolerated (often because it delivers a profitable outcome) and then accepted as ‘normal’. The process of drift is known as the ‘normalisation of deviance’ – and often proceeds without being observed for what it is: a corruption of the norms of the organisation. Occurring in the ‘shadows’ of an organisation’s culture, the mutations are genuinely ‘unseen’ and therefore resistant to correction.

The most common reason for shadow values and principles gaining a foothold during a crisis is that they are ready-made to fill the vacuum caused whenever ethics is reduced to being an ‘optional extra’, or regarded as a luxury that can only be afforded during easier times.

This weakening of commitment to an organisation’s espoused values and principles allows the shadow set to grow in strength.

One of the best examples is that of the German automaker, Volkswagen, where their stated value of ‘excellence’, was mutated into a shadow value of ‘technical excellence’. The resulting decisions led to an emissions scandal that has cost the company a small fortune in fines and severe reputational damage.

Identifying the risk of mutation of the ethical ‘DNA” of an organisation before it occurs, or if this is not possible, having the tools needed to recognise and correct shadow values and principles when they arise will be critical for organisations moving through this next period.

-

Those who ‘survive’ a crisis may suffer the effects of ‘moral injury’ – leading to sub-optimal results for them personally (and their organisation) if the injury is not addressed.

Many people working in business and the professions have already been confronted by the need to make some distressing decisions – not least of which has been to weigh in the balance the good of the organisation versus the livelihood and well-being of employees.

In many cases, the people who lose their jobs will have been loyal and diligent employees who have performed their roles with distinction; roles that are either unaffordable during a recession or that no longer make sense in the emerging strategic environment where the risks posed by the virus are controlled but not eliminated.

Those who make necessary – but unfair – decisions will suffer a certain amount of personal harm from doing so. However, exposure to the risks of such decision making is generally understood to be part of the job. The greater risk is to those people who play no direct part in the decision making but who also feel that they are the inadvertent ‘beneficiaries’ of the sacrifices made by others.

There is much to be learned about this phenomenon by considering the experience of those who survive disasters like shipwreck. The first phase of the disaster will see strangers (and even rivals) driven to work together by the indiscriminate ‘lash of necessity’. People will bend themselves to the task of rowing towards safety – hopeful that a rescuer might be close at hand.

The second phase arises when the situation becomes more desperate … when rations are depleted, when the water is rising toward the gunwales of an overloaded lifeboat. It is then that some place their personal interests before those of all others – throwing overboard any sense of fellow-feeling. Yet, there will be others who decide that they will make the ultimate sacrifice – quietly slipping below the waves so that others survive.

Finally, the moment of rescue comes and the lash is withdrawn. It should be a time of celebration and euphoria. However, it is common for those who survive enter a stage of grief – because they have survived when others, each equally deserving, have not.

‘Moral injury’ is not only experienced by those who made the decision to sacrifice others, or who hoarded goods that could have helped others. The same injury is caused by those who remain without any reason to explain (or justify) their relative good fortune.

Telling any of these people that they should count themselves ‘lucky to have survived’ is worse than useless. Mere survival, as experienced by such people may be a welcome reality – but it is also an ‘empty achievement’ – and does nothing to protect against the consequences of untreated moral injury; which include depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and in the most severe of cases, suicide.

-

The best response to moral injury is to offer the opportunity to find meaning in adversity – a positive reason that justifies continuing effort.

There are only two ways to prevent moral injury. First, one can seek support when making the initial decisions so that, no matter how tough, they do not give rise to a form of regret and self-blame linked to a series of ‘if only’ statements (‘if only I had considered that perspective’, ‘if only I had thought of that option’, ‘if only I had asked one more question’ …).

Second, one can offer a purpose that transcends mere survival. It is only then that the sacrifice of others can be a source of positive motivation. Instead of individuals being beneficiaries, they become ‘stewards’ of a purpose that, if realised, will justify the sacrifices made by others.

Of course, the saving purpose must be something of real substance – not just a few words that make people feel good about themselves. The purpose must be non-trivial, enduring and deep, the kind that people can truly believe in.

However, there is a temporal ‘twist’ at this point. There’s not much point in having a purpose that will rescue an organisation from crisis if decisions made during the crisis render the purpose invalid or unbelievable.

The last thing you want is for those who survive to look back on their experience of crisis and conclude that all that went before makes the purpose seem to be a ‘hoax and the organisation’s leadership a group of hypocrites. That is why it is essential that organisations identify and manage any shadow values or principles that might undermine the better future it must create in the aftermath of the crisis.

In these circumstances, ethics is neither an ‘optional extra’ nor a ‘luxury’. It is a necessity!

The lesson in all of this is relatively simple

Those who wish to prosper in the aftermath of a crisis need to project themselves into the future and identify an underlying purpose that guides their decision making in the present.

Of course, it will be impossible to predict all of the details that define the strategic and tactical environment in which the organisation will need to operate. However, an organisation’s Purpose, Values and Principles (the three principal components of an Ethics Framework) should provide an enduring platform that is serviceable in all environments but one … where there is no genuinely useful role left for the organisation to perform.

Unless that exception exists, organisations and their leaders have an obligation not merely to persist, but to flourish for the sake of all those that made their continued survival possible.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How a Shadow Values Review can improve your organisation

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 31 MAY 2020

If you were to plot a timeline of the Covid-19 pandemic, one way of dividing up the different stages would be by reference to the resources shortage we were facing at the time. First stage: toilet paper and hand sanitiser. Second stage: masks and protective equipment. Third stage: ventilators and hospital beds. Fourth stage: money.

Fortunately, we seem to have skipped stage three in Australia, and for the most part, we’ve addressed shortages in protective equipment and at grocery stores. However, with the focus in Australia now largely on the economic fallout from the pandemic, the question of how to distribute and share limited wealth is now at the front of people’s minds.

Among a range of economic measures introduced to address the Covid-19 crisis, the government has suspended insolvent trading laws for six months. This enables organisations who would otherwise go out of business to continue trading.

Welcomed as a lifeline by many, the question we should be asking is: who is the lifeline for? Should every organisation who is eligible take advantage of the scheme? Whilst it would be tempting, and completely understandable for someone to try to take advantage of every possible support before letting their business go, doing so may well overlook other, more pressing concerns.

John Winter, the CEO of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency & Turnaround Association (ARITA), worries that the six-month safety net might have significant economic impacts later on. “All they are doing is kicking the can down the road,” he says. As a number of businesses take no-interest or low-interest loans to mitigate insolvency, they increase the risk of a more expensive insolvency later on.

“You’re going to have a tsunami of insolvency. You have to have one,” says Winter.

Ethicists use the term ‘moral temptation’ to refer to situations where personal needs and desires are strong enough to override our usual ethical decision-making. Moral temptations aren’t ambiguous ethical choices; rather, they’re situations where the potential benefits for a person are high enough that they might rationalise making a choice that doesn’t hold up to their ethical beliefs. The possibility of keeping a business afloat could generate this kind of situation.

What typically occurs in a moral dilemma is that a person puts disproportionate weight on their own needs and desires, thus overlooking or underestimating the importance of what other people need.

When it comes to the decision to continue trading whilst insolvent, this might mean failing to consider how desperately creditors need their outstanding debts paid. It might mean retaining staff and giving them false hope of ongoing employment, rather than giving them redundancies and the opportunity to seek work elsewhere, whilst unemployment payments are higher than usual. In many cases, it’s unlikely someone taking an objective view would think the benefits of keeping a struggling business afloat were justified, relative to the harms it generates for other groups of people.

“When you are insolvent as a business, you know that you’re not going to pay back the money you owe,” says Winter.

“You can’t get more broke than broke, [but] what you are doing is significantly impacting those that you owe money to,” he adds. “If you’re running a small business, it’s generally other small businesses you owe money to as well. You could actually be sending them broke.”

Here, it might be helpful to consider the kinds of questions that ventilator shortages and other health resource limitations are posing around the world – the kind we’ve managed to avoid here. In New York, where there is a real possibility of healthcare shortages, guidelines indicate that doctors “may take someone who is desperately ill and not likely to live off that ventilator and put someone else with a much better chance on.”

The logic here is simple: when faced with a choice between delaying inevitable, imminent death and restoring someone’s health to live a full life, we should choose the latter.

In many cases, families and patients will decide to remove a ventilator in such cases, knowing that in doing so, they are gifting a lifeline to someone else. For some, the choice is also one that offers considerable relief. Rather than fighting to maintain life, despite the suffering on all involved, they can finally let go.

Winter suggests a similar relief is possible for those whose businesses are in trouble. “When directors finally sit down and say, ‘yeah, I’m done, I’m handing the business over to a liquidator’, they feel a massive sense of relief. They’ve taken so much weight on their shoulders because of the ethical concerns they face around the consequences for others.”

For organisations on the brink of insolvency, the central question seems to be whether to take a lifeline or be a lifeline – resolving matters as best they can, ensuring staff and creditors are cared for – or taking a shot at reviving their business with the help provided?

Before making a choice, organisations facing insolvent trading may wish to consider:

- Do I have justifiable reasons to think that the business will be in a better financial position? Will it be able to pay its debt and meet its obligations in six months time?

- What effects would my decision to continue trading have, whether I am successful or not, on creditors and staff?

- What is the intended purpose behind the suspension? Am I exploiting a loophole or one of the intended beneficiary?

- Are there people who could be saved if I decided to cease trading now? Does the business have any obligations toward those people?

- Is my desire to see this business continue clouding my judgement? Do I need someone independent to help me make this decision?

There is no hard-and-fast rule here. Some organisations will be able to use this support to revive their business to a healthy state. Ideally, those that do have done so in the confidence that the risks they were posing to others were low: they weren’t ‘taking a punt’ with the time available, but making an informed choice about what was in the best interests of the business, creditors, staff and the economy at large.

There is an old saying in military circles: death before dishonour. The question facing some organisations now is just that: when are the social costs too high for me to continue trading? When is it the right thing to do to pull the plug?

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big tech's Trojan Horse to win your trust

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 26 MAY 2020

Technology has created bad trust habits in all of us. We shouldn’t be tricked into giving tech our trust, but that’s exactly what happens when everything is about making life easier.

During this lockdown period, I’ve been thinking a lot about the difference between states and habits. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, we’ve all learned what proper hand washing hygiene looks like, how to prevent the risk of spreading disease when we’re in public and what kinds of places to avoid.

For many of us, health used to be a state that we enjoyed without having to develop too many of the habits that help guarantee that health. We’ve had all the benefit without the effort. However, we’re now recognising that if we want the best chance of maintaining our health in a time of uncertainty, we need to be intentional about the habits and behaviours we develop.

I think it’s helpful to think about trust in the same way. For many people and organisations, being trusted is a state: we want to be in a situation where people have high confidence in us. What hasn’t always happened is to think about the intentional practices, behaviours and habits that are likely to secure trust in times of crisis.

This is particularly true for technology and tech companies, who have enjoyed a disproportionately high level of trust for a simple reason: they make our lives easier. The convenience we receive by interacting with technology means we’re likely to continue to engage with them, even when there are very good reasons not to.

Take Uber, for example. Uber is highly reliable and very convenient, which means people are willing to get into cars with complete strangers. Their behaviour indicates they trust the service, even if they say they don’t (surveys find that people find taxi drivers more trustworthy than Uber drivers). This kind of behavioural trust, born of convenience, holds even in situations where people have very good reasons not to ride.

In 2016, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Jason Dalton – an Uber driver – murdered six people whilst working his nightly Uber driving route. As news broke that there was a suspected murderer picking up rides via Uber, people continued to use the service. One rider who caught a ride with Dalton (thankfully, he wasn’t murdered) actually asked him ‘you’re not the one whose been driving around killing people, are you?’. Despite being aware there was a real threat to life, the convenience of a cheap ride home secured consumer trust in Uber.

Of course, it’s only trust of a certain kind. The trust we confer on convenient technology isn’t genuine trust – where we rationally, consciously believe that our interests align to the tech developers and that they want to take care of us. It’s implied trust; whether we believe the technology will deliver, we act as though it will.

This is the kind of trust we show in large tech platforms like Facebook. A 2018 YouGov survey commissioned by the Huffington Post found 66% of Facebook users have little to no trust in the platforms use of their data. Despite this, those users have given Facebook their data, and continue to do so, which is the kind of trust we provide when there’s something convenient on offer.

We cannot understate the significance that convenience plays as a trust lubricant. Trust expert Rachel Botsman, author of Who Can You Trust?, argues that “Money is the currency of transactions. Trust is the currency of interactions.” We need to add another layer to this: trust is the currency of conscious interactions, but convenience is the currency of the unthinking consumer (and we are all, at times, unthinking consumers).

This generates some real challenges for tech companies. It’s easy to use convenience to secure behavioural trust – to be in the ‘state’ of trust with customers – so that they’ll use your services, hand over data or spend their money, without developing the habits that generate rational, genuine trust. It’s easier to be trusted than to be trustworthy, but it might also be less valuable in the long run.

Moreover, the tendency to reward the convenience-seeking part of ourselves might generate problems with a very long tail. Some problems are not easily solved, nor is there an app to solve wealth inequality, climate change or discrimination. Many of our problems require a willingness to persevere; whilst technology can help, and might help resolve the symptoms of some of these issues, the underlying causes require rethinking our social, political and economic beliefs. Technology alone cannot get us there.

And yet, we continually look to technology as a solution for these woes. The Australian government’s first response to climate change after the 2020 bushfires was a large-scale investment in new climate technologies. Several people have released ‘consent apps’, aimed at preventing rape and false rape claims by having people sign a waiver to confirm they’ve consented to sex. There is no app to solve misogyny; no one technology that will fix our approach to the environment.

The reality is, trading on convenience can make us lazy – not just as individuals, but as a society. It’s bad for us. Moreover, it’s bad for business.

Although people often make decisions based on convenience, they pass judgements based on trust. This means they will often feel duped, exploited or betrayed, feeling ‘tricked’ into signing up to something just because it was convenient at the time.

This makes for a fickle customer and is an unreliable basis on which to build a business. Recognising this, a number of successful organisations are now seeking to build genuine trust. Salesforce CEO Mark Benioff recently stated, “trust has to be the highest value in your company, and if it’s not, something bad is going to happen to you.”

However, for people to trust you, they need to be able to slow down, think, form an ethical judgement. Today, one of the major goals of technology is to be frictionless. Hopefully by now you can see why that’s an unwise goal. If you want people to genuinely trust you, then you can’t give them a seamless experience. You need to create some friction.

Remember, convenience can be a lubricant. It might help you get people through the door more quickly, but it makes them slippery and hard to hold on to.

If you found this article interesting, download our paper, Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology for free to further explore ethical tech. Learn the principles you need to consider when designing ethical technology, how to balance the intentions of design and use, and the rules of thumb to prevent ethical missteps. Understand how to break down some of the biggest challenges and explore a new way of thinking for creating purpose-based design.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 19 MAY 2020

If multinational tech platforms paid more tax on the revenues they made in Australia, would they be in a better moral position to resist government attempts to force them to pay a ‘license fee’ to news media?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

There are a couple of ways to look at this question – one as a matter of principle, the other through the lens of prudence. In terms of principle, I think that we should treat separately the issues of tax and the proposed ‘licence fee’. This is because each issue rests on its own distinct ethical foundations.

In the case of tax, all citizens (including corporate citizens) have an obligation to contribute to the cost of funding the public goods provided by the state. For example, a company like Google shares in the benefits of a society that is healthy, well educated, peaceful and effectively governed under the rule of law. All who draw on and benefit from such public goods should contribute to the cost of their generation and maintenance.

Instinctively, most citizens believe that we should each pay our ‘fair share’ of tax. However, that belief is at odds with the fact that our formal obligation is not to pay a fair amount of tax but, instead, to pay only the amount of tax due to be paid as defined by law. Most of us don’t have much choice about how we discharge this formal obligation – as our taxes are automatically remitted to the Australian taxation Office (ATO) by our employers.

However, most corporations, including Google, have considerable latitude when calculating the tax they think due. For example, corporations have a clear choice about the extent to which they move right to the edge of what the law allows: ‘avoiding’ (which is legal) but not ‘evading’ (which is illegal) tax obligations that, to an ordinary person, might seem to be due.

It is this approach to ‘tax planning’ that allows Google to earn revenue, in Australia, of $4.3B yet only pay tax of $100M. Google has a perfectly rational argument about how this can the case – and relies on the fact that it should only pay tax that is legally due.

However, as is the case with other multinational corporations who make similar calculations, Google’s position fails the ‘pub test’ in that it seems to be unfair? Why? Because it seems inherently improbable (and improper) that such massive local revenue should flow offshore to benefit people who contribute nothing to maintain the society that has made possible such a financial windfall.

The issue of Google paying a ‘licence fee’ to the creators of news content is somewhat different. In general, you’d think it a reasonable expectation that a company pay for the inputs it draws on to make a profit. After all, businesses pay for labour inputs (wages), for financial inputs (interest and dividends), for material inputs (cash outlays), etc. So, why not pay for content that is derived from other sources?

Of course, what’s good for the ‘goose’ should be good for the ‘gander’. Companies like News Corporation and Nine should also be asked if they pay for all of the inputs that they draw on to make a profit? For example, do they pay for all published opinion pieces, or for the interviews they conduct, etc.? However, in general, it seems reasonable to expect that Google (and other companies) should pay for what they derive from others.

Of course, Google does not agree – and is especially opposed to Australian proposals because, if adopted, they will set a precedent that other countries are likely to follow. It is this consideration that leads us to look at the issue through the lens of prudence.

Governments (of all political hues) are especially attentive to the demands of the media. What NewsCorp and Co. want, they usually get … unless opposed by the one force that wields even greater influence over the judgement of politicians – the force of public opinion. So, if Google wishes to prevent or limit the levying of a ‘licence fee’, its most potent ally might have been the Australian public.

However, the electorate is unlikely to back the interests of a company that is perceived not to back the interests of the people whose taxes provide the infrastructure on which Google depends for the enrichment of its overseas owners.

This is where principle and prudence align. Google (and other multinational corporations) should pay taxes that amount to a fair contribution to the maintenance of public goods. Had it done so, then Google might have many more friends who might stand beside it in its battle with other powerful corporations like NewsCorp and Nine.

I am not sure if arguments from principle or prudence will really carry much weight. Perhaps the situation needs to be expressed in the language of financial self-interest. Compared to a licence fee (which might be as high as $1B per annum), would a less aggressive approach tax planning have have been a good investment?

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pavan Sukhdev on markets of the future

LISTEN

Business + Leadership

Leading With Purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

AI can slowly shift an organisation’s core principles. Here’s how to spot ‘value drift’ early

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are we ready for the world to come?

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 15 MAY 2020

We are on the cusp of civilisational change driven by powerful new technologies – most notably in the areas of biotech, robotics and expert AI. The days of mass employment are soon to be over.

While there will always be work for some – and that work is likely to be extremely satisfying – there are whole swathes of the current economy where it will make increasingly little sense to employ humans. Those affected range from miners to pathologists: a cross-section of ‘blue collar’ and ‘white collar’ workers, alike in their experience of displacement.

Some people think this is a far too pessimistic view of the future. They point to a long history of technological innovation that has always led to the creation of new and better jobs – albeit after a period of adjustment.

This time, I believe, will be different. In the past, machines only ever improved as a consequence of human innovation. Not so today. Machines are now able to acquire new skills at a rate that is far faster than any human being. They are developing the capacity for self-monitoring, self-repair and self-improvement. As such, they have a latent ability to expand their reach into new niches.

This doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Working twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week in environments that no human being could tolerate, machines may liberate the latent dreams of humanity to be free from drudgery, exploitation and danger.

However, society’s ability to harvest the benefits of these new technologies crucially depends on planning and managing a just and orderly transition. In particular, we need to ensure that the benefits and burdens of innovation are equitably distributed. Otherwise, all of the benefits of technological innovation could be lost to the complaints of those who feel marginalised or abandoned. On that, history offers some chilling lessons for those willing to learn – especially when those displaced include representatives of the middle class.

COVID-19 has given us a taste of what an unjust and disorderly transition could look like. In the earliest days of the ‘lockdown’ – before governments began to put in place stabilising policy settings such as the JobKeeper payment – we all witnessed the burgeoning lines of the unemployed and wondered if we might be next.

As the immediate crisis begins to ease, Australian governments have begun to think about how to get things back to normal. Their rhetoric focuses on a ‘business-led’ return to prosperity in which everyone returns to work and economic growth funds the repayment of debts accumulated during the the pandemic.

Attempting to recreate the past is a missed opportunity at best, and an act of folly at worst. After all, why recreate the settings of the past if a radically different future is just a few years away?

In these circumstances, let’s use the disruption caused by COVID-19 to spur deeper reflection, to reorganise our society for a future very different from the pre-pandemic past. Let’s learn from earlier societies in which meaning and identity were not linked to having a job.

What kind of social, political and economic arrangements will we need to manage in a world where basic goods and services are provided by machines? Is it time to consider introducing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) for all citizens? If so, how would this be paid for?

If taxes cannot be derived from the wages of employees, where will they be found? Should governments tax the means of production? Should they require business to pay for its use of the social and natural capital (the commons) that they consume in generating private profits?

These are just a few of the most obvious questions we need to explore. I do not propose to try to answer them here, but rather, prompt a deeper and wider debate than might otherwise occur.

Old certainties are being replaced with new possibilities. This is to be welcomed. However, I think that we are only contemplating the ‘tip’ of the policy iceberg when it comes to our future. COVID-19 has given us a glimpse of the world to come. Let’s not look away.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

READ

Business + Leadership

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 13 MAY 2020

My employer sent me a questionnaire designed to test if my home working environment meets basic standards. If I’d answered truthfully I would have ‘failed the test’. But what’s the point in telling the truth when I have to work at home in any case? Was it wrong to lie on the form?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

Although this ethical issue seems to fall on you – as the person receiving the survey – it actually starts with your employer’s decision to request this information in the first place. I assume they did so in order to meet their legal obligations … and perhaps conditions set by their insurer, etc.

However, the process they activated was not designed to cope with circumstances like the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the occupational health and safety checks they are trying to use were developed for a time when working from home was the exception – rather than the rule.

Back then, it made excellent sense to check that those opting to work from home could do so with good lighting, an ergonomic chair … and all the other requirements one would reasonably expect to find in a safe, modern office environment.

However, for the time being, millions of people have no choice but to plonk themselves down a couch or at a kitchen table or … wherever … to work as best they can.

So, let’s imagine that your home environment is not especially suited for work? Suppose you pass on this information to your employer. Do we really think that they would rush over with a well-designed desk, chair, light, etc.?

Perhaps some might do so … but in the current circumstances I doubt that this would be the response. Even if one sets aside questions of cost – are there enough new chairs, desks, computers, etc. to make good the likely deficiencies in the working arrangements of a large percentage of the active workforce? I suspect not.

Given this, I imagine that many people have decided to collude (with their employer) in a ‘white lie’. Both sides know (but will not say) that to offer an honest response would probably be an exercise in futility.

With this in mind, ‘form’ triumphs over ‘substance’ – with employees signing off on a declaration that they know not to be strictly true – but that is practically required all the same.

Now, I know that thus might seem to be a fairly minor form of deception – something to be excused because deemed to be ‘necessary’. However, I reckon that it is never a good thing to lie – and that those who plead ‘necessity’ must first do everything they can to prevent this kind of dilemma from arising in the first place.

This is because even occasional acts of dishonesty can start to warp a culture because they suggest that core values and principles can be abandoned whenever the going gets tough.

In summary: I think it was wrong to lie on the form (even if understandable). However, it would have been far better – for all – if your employer had not put you in this invidious position in the first place.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Bryan Mukandi The Ethics Centre 9 MAY 2020

In their recent article, ‘Who gets the ventilator in the coronavirus pandemic?’, bioethicists Julian Savulescu and Dominic Wilkinson note that we may soon be faced with a situation in which the demand for medical resources is greater than what is available.

At that point, decisions about who gets what medical resources ought to be just, they argue. The trouble with the article however, is that the two men seem to approach our present crisis as though it were just that, a present tense phenomenon. They view COVID-19 not as a something that has emerged over time as a result of our social configuration and political choices, but as something that appeared out of nowhere, an atemporal phenomenon.

Treating the pandemic as atemporal means that the two scholars only focus on the fact of this individual here and that one over there, suffering in this moment, from the same condition. They fail to ask how how this person came to be prone to the virus, or what resources that person has had at their disposal, let alone the socio-political and historical circumstances by which those resources were acquired. Karla Holloway, Professor of English and Professor of Law, makes the point that stripping away the textual details around our two patients simplifies the decision making process, but the price paid for that efficiency might be justice.

We know that there are systematic discrepancies in medical outcomes for marginalised groups at the best of times.We know that structural inequalities inform discrepancies around the degree to which people can practice social distancing and reduce the risk of infection. We know that those most likely to be most severely affected in the wake of the pandemic are those belonging to already marginalised communities. As public health medicine specialist, Papaarangi Reid, put it in a recent interview:

“We’ve got layers that we should be worried about. We should be worried about people who have difficulty accessing services … people who are stigmatised … While we are very worried about our elderly, we’re also worried about our precariat: those who are homeless; we’re worried about those who are impoverished; those who are the working poor; we’re worried about those who are in institutions, in prisons.”

Every time Reid says that we ought to worry about this group or that, I am confronted by Arendt’s take on just how difficult it is to think in that manner. I’m currently teaching a Clinical Ethics course for second year medical students, one of whose central pillars is Hannah Arendt’s understanding of thought. Standing on the other side of the catastrophe that was the second world war, she warned that thinking is incredibly difficult; so much so it demands that one stop, and it can be paralysing.

Arendt pointed out those algorithmic processes on the basis of which we usually navigate day-to-day life: clichés, conventional wisdom, the norms or ‘facts’ that seem so self-evident, we take them for granted. She argued that those are merely aids, prostheses if you like, which stand in the place of thinking – that labour of conceptually wading through a situation, or painstakingly kneading a problem. The trouble is, in times of emergency, where there is panic and a need for quick action, we are more likely to revert to our algorithms, and so reap the results of our un-interrogated and unresolved lapses and failures.

Australia today is a case in point. “The thing that I’m counting on, more than anything else,” noted Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently, “Is that Australians be Australian.” He went on to reiterate at the same press conference, “So long as Australians keep being Australians, we’ll get through this together.”

I’m almost sympathetic to this position. A looming disaster threatens the status quo, so the head of that status quo attempts to reassure the public of the durability of the prevailing order. What goes unexamined in that reflex, however, is the nature of the order. The prime minister did not stop to think what ‘Australia’ and ‘Australianness’ mean in more ordinary times.

Nor did he stop to consider recent protests by First Nations peoples, environmental activists, refugee and asylum seeker advocates and a raft of groups concerned about those harmed in the course of ‘Australians being Australian’. Instead, with the imperative to act decisively as his alibi, he propagated the assumption that whatever ‘Australia’ means, it ought to be maintained and protected. But what if that is merely the result of a failure to think adequately in this moment?

In his excellent article, calling on the nation to learn from past epidemics, Yuggera/Warangu ophthalmologist Kris Rallah-Baker, writes: ‘This is just the beginning of the crisis and we need to get through this together; Covid-19 has no regard for colour or creed’. In one sense, he seems to arrive at a position that is as atemporal as that of Savulescu and Wilkinson, with a similar stripping away of particularity (colour and creed). It’s an interesting position to come to given the continuity between post-invasion smallpox and COVID-19 that his previous paragraphs illustrate.

Read another way, I wonder if Rallah-Baker is provoking us; challenging us to think. What if this crisis is not the beginning, but the result of a longstanding socioeconomic, political and cultural disposition towards First Nations peoples, marginalised groups more broadly, and the prevailing approach to social organisation?

Could it then also be the case that the effect of the presence of novel coronavirus in the community is in fact predicated, to some degree, on social categories such as race and creed? Might a just approach to addressing the crisis, even in the hospital, therefore need to grapple with temporal and social questions?

There will be many for whom the days and weeks ahead will rightly be preoccupied with the practical tasks before them: driving trucks; stacking supermarket shelves; manufacturing protective gear; mopping and disinfecting surfaces; tending to the sick; ensuring the continuity of government services; and so forth. For the rest of us, there is an imperative to think. We ought to think deeply about how we got here and where we might go after this.

Perhaps then, as health humanities researchers Chelsea Bond and David Singh recently noted in the Medical Journal of Australia:

“we might also come to realise the limitations of drawing too heavily upon a medical response to what is effectively a political problem, enabling us to extend our strategies beyond affordable prescriptions for remedying individual illnesses to include remedying the power imbalances that cause the health inequalities we are so intent on describing.”

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

BY Bryan Mukandi

is an academic philosopher with a medical background. He is currently an ARC DECRA Research Fellow working on Seeing the Black Child (DE210101089).

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

Emerging from the turbulence of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to escape the hold of our past and use moral imagination to explore a better future.

After months of living through disruption, old work habits and perceptions may no longer fit the ‘new normal’, says Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School.

“There’s a very positive side to this, because it makes us realise that the seemingly obvious, natural way of operating is not so obvious anymore.” says Baur.

“It does afford us the ability to think a little bit more carefully about what we’re doing.”

A simple example may be that, after mastering virtual meetings, we realise that the regular face-to-face interstate meetings we thought to be essential are not, in fact, a necessary part of doing business. Instead of asking ‘can we do this online?’ we might now ask, ‘should we do this online, is there a good reason to do it in person?’

“It’s liberating, potentially, to be able to be thrown back and see that the seemingly natural is really not so natural and obvious after all,” says Baur.

Aspects of life previously unquestioned, such as our choices of where to live, send our kids to school or even the jobs we do, may be cast in a different light.

Speaking with Bob McCarthy, an Irish colleague, he spoke of the experience of the ‘Celtic Tigers’ during ten-year-plus period of economic growth prior to 2008. “Ireland had never experienced anything like it and our economy became the envy of the world. Of course, we lived in accordance with our new wealth and fame – two houses each, BMWs, ski holidays and buying chalets in Morzine”, says McCarthy.

Many rationalised their good fortune – ‘we’ve had it tough for so long we deserve a little luxury.’ So, when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) crash came, it came hard. There was a 60% average fall in property prices, high unemployment, many family tragedies, house repossessions and years of debt to repay.

Bob said that the experience of crisis changed attitudes and behaviours, “Now, those of us who have been through this look at life, business, money, relationships, values, ethics through a different filter than before”.

He describes the experience of having benefitted from the pain. What had once seemed important during the times of excess are no longer important. What didn’t matter then, matters to him now. “Don’t get me wrong – not everything has changed. But for most the filter we use has changed”.

Baur says that, with the experience of COVID-19, we now have a similar opportunity to reset our aspirations, “When we were riding easy, just several weeks ago, we were in a state of deception.” He recognises that the pandemic has caused major economic shocks – perhaps even more severe than those caused by the GFC, “And now we can regroup. That seems to me a more positive, healthy way of thinking of it – that all of this wealth and expectation was not really ours to have to begin with.”

Bigger is not always better

The aftermath of the pandemic presents a good time to reassess our attitude to growth. The fact that almost all sectors of business have suffered means that there is a collective opportunity to slow down and reassess whether the purpose of business is to make more money for money’s sake, or to provide for human need.

Business is now attending to issues that were always there to be addressed – but remained largely ‘unseen’. By presenting itself as a ‘common enemy’, COVID-19 has caused us all to look up at the same time and respond to a suite of collective problems.

In many cases, our response has been an expression of human goodness, compassion and altruism. ‘Them’ has become ‘us’.

For example, Accor hotels, is opening up unused accommodation to support vulnerable people. Simon McGrath, Accor’s CEO, says, “Our doors are open,” said Accor’s McGrath “We have accommodation assets that can help people in times of need, and while the industry’s been devastated commercially, it doesn’t mean we can’t help.”

In a similar vein, UBER has partnered with the Women’s Services Network to provide 3,000 free rides to support those needing safe travel to or from shelters and domestic violence support services.

Australia was relatively unscathed by the GFC of 2008 and did not experience the large economic downturn felt elsewhere on the globe. Australia has also managed to flatten the curve and “none have been more successful than Australia and New Zealand at containing the coronavirus,” said Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

This is thanks to our strong public health system and our comprehensive testing regime, to the tracing of carriers and our strict self-isolation and physical distancing laws. We were also lucky that our geographic isolation bought us an extra 10 precious days to prepare.

However, Australia has not and will not escape the economic consequences of the pandemic – and our response to the threat it poses. So, how will we shape up when the challenge is an economic recession as opposed to a medical emergency? Will the good will and sense of common endeavour persist during the next phase of struggle? More interestingly still, will the sense of mutual obligation survive a return to posterity? Or will we resume our ‘old ways’?

Baur says an argument could be made that business and society in general did not make the most of the lessons to be learned from the GFC, more than a decade ago. Ireland’s Bob McCarthy, is of the same opinion, “We may be having an opportunity that would have been a lost opportunity from that time,” he says.

“What might be seen as a loss of opportunity, a loss of growth, in one limited respect, is really a darn good thing for everybody,” Baur says.

Echoing the same sentiment, Mike Bennetts CEO of Z Energy in New Zealand told audiences at the Trans – Tasman Business Circle that this virus has accelerated us into the future by 5 years, so “let’s make the most of it”. Our instinct is to seek comfort and confidence in the known which will mean going back to the way it was.

The challenge, now, is not only to create a new future but a better future. For that to happen we need to unleash a better version of ourselves.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Reports

Business + Leadership