Big Thinker: Marcus Aurelius

If you became a Roman Emperor, would you have maintained your humility? That’s one of the things Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE), the “Stoic philosopher king”, was known for.

Adopted by his uncle, the Emperor of Rome, when he was a young man, Marcus spent his adult life learning the business of government, including serving as consul (chief magistrate) for three separate years.

Prior to becoming Emperor, Marcus also began forming an interest in philosophy. In particular, the writings of the former slave Epictetus (55 BCE–135 CE), a renowned thinker of Stoic moral philosophy. This would turn out to be the influence of one of Marcus’ greatest legacies, the Meditations.

Meditations and Stoicism

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius is a series of twelve books containing personal notes and ideas for self-guidance and self-improvement. Scholars believe it’s unlikely that it was ever written to be seen, but rather that the books are akin to a journal, written in private for his own moral improvement, to reinforce in himself the Stoic doctrines that he aimed to live and rule by.

Marcus wrote these meditations during the second decade of his reign and last decade of his life, during which he was campaigning to take back and expand parts of his empire after enduring years of plague and invasion.

He saw the philosophy of Stoicism as the principal guidance for his life and writing, though quotes from many other philosophies can be found in his books.

Stoicism is an ancient philosophy whose ethics propose a focus on reason and happiness (flourishing). It says, like many philosophies at the time, that the rational person’s ultimate goal is to live happily.

Unique to Stoicism, though, is the idea that the only thing needed for happiness is virtue. To live perfectly virtuously is to be happy, regardless of external constraints or effects. This leads to a difficult conclusion, but one that the Stoics maintain: a virtuous person being tortured for example, is still maximally happy, since they still possess the one beneficial quality, virtue.

It follows from this, say the Stoics, that happiness is fully within our personal control. Marcus’ writing to himself reinforces this idea in various ways, supporting himself through the difficulties of Roman life, not to mention a ruler during conflict.

“Such as are your habitual thoughts, such also will be the character of your mind; for the soul is dyed by the thoughts.”

One of the main teachings of Stoicism is acceptance. This is where the common misunderstanding of Stoicism being restraint comes from. Many believe that it encourages the bottling or rejecting of emotion. Rather, it says that virtuous people are not overcome by impulsive and excessive emotion.

This is not because Stoics believed that we must restrain ourselves. Instead, they believed that we find virtue through knowledge. Then, once we properly obtain the knowledge that coincides with our rationality and nature, we will freely accept the reality of things that once may have caused us grief (or joy).

“If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”

Marcus used these teachings to guide himself, as is evident in the many quotes that continue to circulate in pop culture. Some of these speak of the importance of endurance in the pursuit of virtue, believing that challenges are an opportunity to strengthen character. Others speak of the importance of gratitude in responding to the perceived highs and lows of life.

“Do not indulge in dreams of having what you have not, but reckon up the chief of the blessings you do possess, and then thankfully remember how you would crave for them if they were not yours.”

Marcus Aurelius left a legacy that has lingered across cultures and centuries to continue guiding people on their journeys of self-improvement.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The power of community to bring change

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his explanation of the role of government as an insurer of security, which has had an enduring influence on understandings of political philosophy.

Living through the displacement of the English Civil War (1642-1651), Hobbes was grappling with the question of how societies could keep peace and ensure stability, amid conflict and self-interest. The period was marked by social upheaval with the collapse of royal authority, clashes between the government and monarchy and insecurity, which led to him thinking about the manifestations of power, the human condition and the role of government.

His approach to understanding human behaviour was methodical and scientific, being deeply influenced by the scientific revolution of the time. Hobbes believed that human societies, like physical systems, could be understood through cause and effect and that understandings of order and stability were derived from the predictability of human behaviour and power structures.

The state of nature

It was from this historical and intellectual backdrop that Hobbes produced his most famous work, Leviathan (1651). His masterwork Leviathan: The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, garnered him fame for creating what would later become known as the Social Contract Theory, a framework that explains and justifies the exchange that free, equal and rational citizens make in surrendering certain freedoms in return for collective order and protection. This same contract also serves to provide legitimacy to governments and their use of power and authority over citizens.

In Leviathan and his other work, Hobbes disagrees with Aristotle that humans are naturally suited to life as citizens within a state. Hobbes instead argues that humans are not equipped to be rational citizens, as we are easily swayed, often short sighted and highly competitive. He believes these characteristics make humans more predisposed to violence and war rather than political order, with no natural self-restraint. Hobbes states that in this state of nature, without government and order, the life of man is “poor, nasty, brutish and short”, largely due to the insecurity and conflict. Everyone is free and equal, without any rules or restrictions to their actions and coupled with a self interested nature and limited resources, life in this state is a constant struggle.

The social contract

To escape this constant struggle in this state of nature, Hobbes argues that people, through reason, collectively agree to create a social contract. Hobbes believes that political order is only formed when human beings voluntarily give up some of their rights and freedoms, in exchange for order and security from a common authority, the leviathan (a ruler).

Hobbes uses the Leviathan as a metaphor for a powerful ruler or government that embodies the collective will of the people, possessing absolute authority to maintain peace and prevent society from descending back into chaos. Hobbes conception of a social contract and the role of the sovereign or leviathan, refers to these key characteristics:

- The sovereign or leviathan’s power must be absolute – only one authority, as divided power invites factionalism.

- The contract is driven by the purpose of security.

- Individuals cannot revoke the contract once it’s been made, as it would risk bringing back chaos.

- The contract is between the people and the sovereign is not party to this agreement. However, if the sovereign fails to maintain peace and security, the contract loses legitimacy and people return to the state of nature.

This framework for the social contract theory by Hobbes, was adopted by John Locke and Jean-Jaques Rousseau. However, they differed from Hobbes by offering a more optimistic view of human behaviour and the role of government. Critical responses tended to focus on a lack of accountability measures on the leviathan who has expansive absolute power. Locke for example took a liberal view, involving limited government and argued the leviathan was mutually obligated within a social contract, rather than subjects being expected to obey unconditionally to avoid the collapse of civil society.

Hobbes’s ideas continue to shape how government and authority is understood. While very few modern states reflect the vision of an absolute sovereign, the core principles of the social contract theory remain central to political thought. The consent of citizens to be governed in exchange for protection and the rule of law persists. However, in modern liberal democracies, the power of governments is placed under greater scrutiny through constitutions, elections and other checks and balances. Hobbes’s theory provides the foundation for understanding why societies form governments, even as modern democracies reinterpret his ideas to prioritise liberty, representation, and accountability alongside security and order.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big thinkerSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 7 OCT 2025

Ayn Rand (born Alissa Rosenbaum, 1905-1982) was a Russian-born American writer & philosopher best known for her work on Objectivism, a philosophy she called “the virtue of selfishness”.

From a young age, Rand proved to be gifted, and after teaching herself to read at age 6, she decided she wanted to be a fiction writer by age 9.

During her teenage years, she witnessed both the Kerensky Revolution in February of 1917, which saw Tsar Nicholas II removed from power, and the Bolshevik Revolution in October of 1917. The victory of the Communist party brought the confiscation of her father’s pharmacy, driving her family to near starvation and away from their home. These experiences likely laid the groundwork for her contempt for the idea of the collective good.

In 1924, Rand graduated from the University of Petrograd, studying history, literature and philosophy. She was approved for a visa to visit family in the US, and she decided to stay and pursue a career in play and fiction writing, using it as a medium to express her philosophical beliefs.

Objectivism

“My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” – Appendix of Atlas Shrugged

Rand developed her core philosophical idea of Objectivism, which maintains that there is no greater moral goal than achieving one’s happiness. To achieve this happiness, however, we are required to be rational and logical about the facts of reality, including the facts about our human nature and needs.

Objectivism has four pillars:

- Objective reality – there is a world that exists independent of how we each perceive it

- Direct realism – the only way we can make sense of this objective world is through logic and rationality

- Ethical egoism – an action is morally right if it promotes our own self-interest (rejecting the altruistic beliefs that we should act in the interest of other people)

- Capitalism – a political system that respects the individual rights and interests of the individual person, rather than a collective.

Given her beliefs on individualism and the morality of selfishness, Rand found that the only political system that was compatible was Laissez-Faire Capitalism. Protecting individual freedom with as little regulation and government interference would ensure that people can be rationally selfish.

A person subscribing to Objectivism will make decisions based on what is rational to them, not out of obligation to friends or family or their community. Rand believes that these people end up contributing more to the world around them, because they are more creative, learned, and can challenge the status quo.

Writing

She explored these concepts in her most well-known pieces of fiction: The Fountainhead, published in 1943, and Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957. The Fountainhead follows Howard Roark, an anti-establishment architect who refuses to conform to traditional styles and popular taste. She introduces the reader to the concept of “second-handedness”, which she defines living through others’ and their ideas, rather than through independent thought and reason.

The character Roark personifies Rand’s Objectivist ideals, of rational independence, productivity and integrity. Her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, builds on these ideas of rational, selfish, creative individuals as the “prime movers” of a society. Set in a dystopian America, where productivity, creativity, and entrepreneurship stagnate due to over-regulation and an “overly altruistic society”, the novel describes this as disincentivising ambitious, money-driven people.

Even though Atlas Shrugged quickly became a bestseller, its reception was controversial. It has tended to be applauded by conservatives, while dismissed as “silly,’ “rambling” and “philosophically flawed” by liberals.

Controversy

Ayn Rand remains a controversial figure, given her pro-capitalist, individual-centred definition of an ideal society. So much of how we understand ethics is around what we can do for other people and the societies we live in, using various frameworks to understand how we can maximise positive outcomes, or discern the best action. Objectivism turns this on its head, claiming that the best thing we can do for ourselves and the world is act within our own rational self-interest.

“Why do they always teach us that it’s easy and evil to do what we want and that we need discipline to restrain ourselves? It’s the hardest thing in the world–to do what we want. And it takes the greatest kind of courage. I mean, what we really want.”

Rand’s work remains hotly debated and contested, although today it is being read in a vastly different context. Tech billionaires and CEOs such as Peter Thiel and Steve Jobs are said to have used her philosophy as their “guiding stars,” and her work tends to gain traction during times of political and economic instability, such as during the 2008 financial crisis. Ultimately, whether embraced as inspiration or rejected as ideology, Rand’s legacy continues to grapple with the extent to which individual freedom drives a society forward.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Political aggression worsens during hung parliaments

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

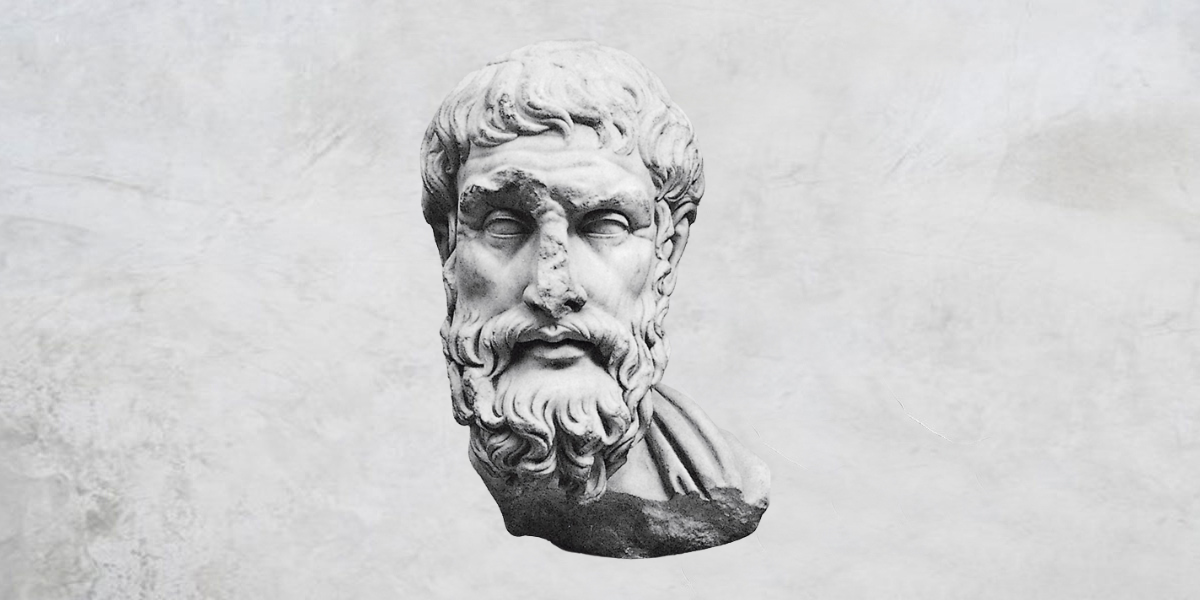

Big Thinker: Epicurus

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher and founder of the highly influential school of philosophy, Epicureanism.

In a time dominated by Platonism, Epicurus established a competing school in Athens known as “the Garden”. Many of his teachings were direct contradictions of the teachings of Plato, other schools of thought and generally accepted ideas in areas like theology and politics. He also flouted norms of the time by openly allowing women and slaves to join and participate in the school.

Though he strongly insisted otherwise, dubbing himself “self-taught”, records indicate Epicurus was greatly influenced by many philosophers of and before his time such as Democritus, Pyrrho and Plato.

Theology and Ethics

Two significant departures from the popular ancient Greek thought involved Epicurus’ ideas about theology. In general, he was critical of popular religion, though in a much more restrained way than his later followers.

One departure was his thoughts on the afterlife. Epicurus believed that there was no afterlife, and that any belief in it, especially the idea that the afterlife could involve punishment and suffering, was a harmful superstition that prevented people from living a good life.

“Accustom thyself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply sentience, and death is the privation of all sentience; . . . Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.”

From Letter to Menoeceus

Another departure was his thoughts on the gods, and specifically their involvement in human affairs, also known as divine providence. Unlike most, Epicurus believed in the gods while simultaneously believing that they were completely removed from the mortal realm and uninvolved in human affairs.

The Epicurean view of the gods was that they were perfect beings, and involvement in anything outside their perfection would tarnish that perfection. The view denies that they exhibit any control over humans or the world, and that they instead function mainly as aspirational figures – beings to admire and emulate.

Both of these departures from popular ancient Greek religion came from his unique hedonistic philosophy. Epicurus believed that the ultimate purpose of philosophy was to achieve, and help others to achieve, certain states of being that characterise the eudaimonic (happy, flourishing) life.

Specifically, he thought that eudaimonia was attained through internal peace (ataraxia), an absence of pain (aponia) and a life of friendship.

This was the basis of his hedonism – unique in that he defined pleasure as an absence of suffering and so had a far greater focus on moderation than what is typically associated with hedonism.

In fact, Epicurus was disapproving of excessiveness generally:

“…the pleasant life is produced not by a string of drinking bouts and revelries, nor by the enjoyment of boys and women, nor by fish and the other items on an expensive menu, but by sober reasoning.”

These ideas informed his theological thoughts. He believed that a belief in the afterlife was superstitious and bad because it was most often a source of fear. Instead of acting morally to avoid the risk of punishment in the afterlife, which causes suffering in the current life, Epicurus taught that we should instead act morally because we will inevitably suffer from guilt or the fear of being discovered if we do not.

Likewise, he taught that while the gods had no interest in the affairs of humans, we should still act morally and kindly because those who do will have no fear, leading to ataraxia.

“…it is not possible to live pleasurably without living sensibly and nobly and justly.”

Pleasure and Desire

As part of his ethical teachings, Epicurus noted different types of pleasures and desires that prevent us from achieving a life free from suffering and trouble.

He was particularly focused on desire because he saw it, like fear, as a ubiquitous source of suffering. He taught that there are three kinds of desires: two natural, and one empty. Natural desires can be necessary (like food or shelter) or unnecessary (like luxury food or recreational sex). Empty desires on the other hand correspond to no genuine, natural need and often can never be satisfied (wealth, fame, immortality), leading to continuous pain of unfulfilled desire.

Unfortunately, like many Hellenistic philosophers, the vast majority of Epicurus’ writings have remained undiscovered, instead pulled together largely through the writings of contemporaries, followers and later historians. Despite this, his ideas have resurfaced throughout the centuries since and influenced the thinking of ancient and modern philosophers alike.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

Big thinkerClimate + Environment

BY Cameryn Cass 5 JUN 2024

Despite centuries of advocacy urging us to consider our actions, the urgent problem of climate change and conservation of our earth is one that often feels the most insurmountable.

In celebration of World Environmental Day, these seven key thinkers and activists from across history have contributed to our ethical understanding of the environment and how we can lessen our impact.

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)

Aldo Leopold was a conservationist, forester, philosopher, and educator who dedicated his life to coexisting with nature and learning from it, with many considering him to be the father of American wildlife ecology.

His non-fiction book, A Sand County Almanac, calls for the development of a land ethic, as conservation is unachievable so long as resources are controlled by economic interests. He wrote, “a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it.” By including land in our understanding of community, it no longer is property; instead, it becomes inherently valuable and, in turn, worthy of protection and respect. “We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in,” he wrote.

Leopold additionally stressed the need to evaluate and update the content of our conservation education. He said it’s not enough to join a few organisations, follow the law, and trust the government will do the rest. “In our attempt to make conservation easy, we have made it trivial.”

Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1933-present)

Nasr, an internationally celebrated thinker from Iran, is, at present, a professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University. He looks at the natural world through a religious lens, thus becoming the founder of environmentalism in the Muslim world. He calls Islam a “green religion,” as it’s easy for followers to sympathise with the natural world, since “the Qur’an addresses not only human beings, but also the cosmos. All creatures participate in Islam.” In Islam, all living things are equally valuable, equally deserving of life, equally valid. Nasr highlights how “we human beings cannot be happy without the happiness of the rest of creation. We have killed enough, massacred enough of God’s other creatures.”

He juxtaposes Islamic values with Christian ones, and how the latter’s “most devout followers don’t show much interest in the environment.” In all the verses of the New Testament, he points out, there’s not one mention of nature. “To be modern is to destroy the world of nature. That’s the great tragedy of it, and we should try to find out why.”

Naomi Klein (1970-present)

As a Canadian journalist, filmmaker, New York Times best-selling author and professor of climate justice, Naomi Klein’s commitment to activism spans many mediums, across borders. She sees our world’s current state as one major, interconnected problem: Climate change isn’t separate from medical crises which aren’t separate from political crises, and so on. In her eyes, it’s all connected and it all rests on the initial sin of stealing lands from Indigenous people.

In her Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2015 talk, Capitalism and the Climate, she emphasised the Pope’s idea of a “throwaway culture.” It’s what’s allowed generations of Australians, Canadians, and Americans alike to take from Native people, and it’s the same concept that’s degrading and destroying our planet. “We extract and do not replenish and wonder where the fish have disappeared. And why the soil requires evermore inputs, like phosphates, to stay fertile.” Klein calls for the creation of a “culture of caretaking in which no one and nowhere is thrown away. In which the inherent value of people and all life is foundational.”

Tyson Yunkaporta (present)

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for over 65,000 years – far longer than any other humans have anywhere else on the planet. Tyson Yunkaporta, an Aboriginal scholar and author, believes that we stand to resolve a lot of our current environmental problems by turning to their ancient practices, or, at the very least, considering them. Aboriginal “patterns still flow with the movement of the earth.” They remain connected to the planet, he said, living in harmony and coexisting with the natural world in ways non-Indigenous people do not.

Yunkaporta thus encourages readers to question Western thinking and approach problems with an Aboriginal lens instead. As he wrote in his book, Sand Talk, we ought “to live and work in accordance with a natural order, rather than against it.”

Pythagoras (570 BC-495 BC)

Though Pythagoras is typically remembered for his contribution to mathematics (you might remember his famed Pythagorean Theorem from high school math class) he was actually better known for his beliefs on reincarnation and diet in his day. In fact, he was the first modern vegetarian in the West and is regarded as the father of ethical vegetarianism.

While the actual impact of cutting out meat from one’s diet is often disputed, individuals can have impact by lessening their own ecological footprint. By cutting out meat, it can be argued that one stands to dramatically reduce the resources – like land, water, and oil – required to sustain their diet. Pythagoras far predated these ecological footprint considerations; instead, he grounded his vegetarian beliefs in reincarnation. By killing animals and eating their meat, he said, we run the risk of eating our companions. “Meat is for beasts to feed on… what a wicked thing it is for flesh to be the tomb of flesh… for one live creature to continue living through one live creature’s death.”

Vandana Shiva (1952-present)

Vandana Shiva is an ecofeminist, physicist, ecologist, activist, editor, and author known for her steadfast commitment to work in environmental conservation, specifically agriculture. Famously, she opposed Asia’s Green Revolution, which, while ramping up food production in less-developed countries, the heavy use of pesticides harmed native seed diversity and traditional agricultural practices.

To try and do her part to give back, in 1982, Shiva founded the Research Foundation for Science, Technology, and Ecology to develop sustainable agricultural practices. In her Festival of Dangerous Ideas talk in 2013, Growth = Poverty, she condemns GDP and growth, drawing on experiences from life in India. Gross Domestic Product, she says, doesn’t account for things like pollution in the rivers, and if it did, India and China would have negative scores. Instead, it creates a false standard of living and, in doing so, “it has perpetuated a model of generating non-sustainability, inequality, and a deep violence within society and within the self.”

Kongqiu (551 BC-479 BC)

Better known as Confucius, this ancient Chinese philosopher’s teachings are, to this day, the bedrock of East Asian culture.

Confucius believed that all life has qi, which is essentially life force that nurtures humans and nature alike. In essence, qi supports the idea that humans and nature are isogenous, of the same origin and interconnected. In accordance with this perspective, Confucius stressed that humans ought to be kind to the land to achieve harmony and balance.

Present day scholars look to this ancient Chinese wisdom as a piece to solving the puzzle that is climate change. If humans adopted the idea that we are not separate from nature and instead an extension of it, as Confucius said, then perhaps we’d see this destruction to the land as destruction to ourselves and finally change our unsustainable ways.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

BY Cameryn Cass

Cameryn Cass is a curious writer and an editor-in-training who studied at Michigan State University. Her primary focus is environmental storytelling, as she deeply loves the natural world and intends to use her voice to defend it. Outside of work, she loves to hike, rock climb and practice yoga.

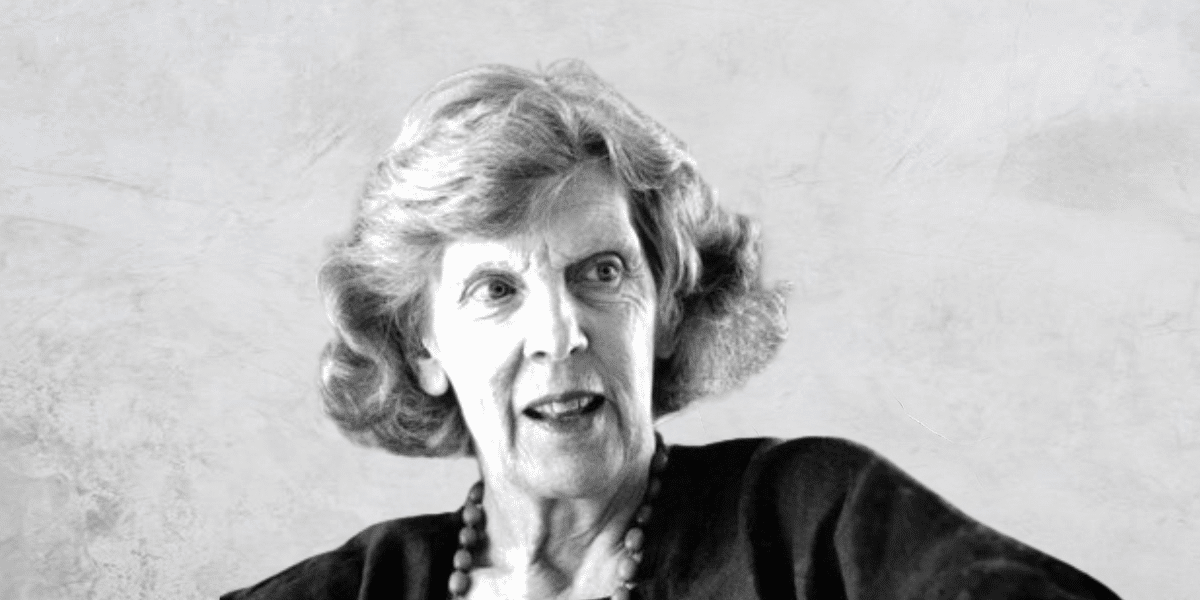

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Philippa Foot (1920-2010) is one of the founders of contemporary virtue ethics, reviving the dominant Aristotelian ethics in the 20th century. She introduced a genre of decision problems in philosophy as part of the analysis in debates around abortion and the doctrine of double effect.

Philippa Foot was born in England in 1920. While receiving no formal education throughout her childhood, she obtained a place at Somerville College, one of the two women’s colleges at Oxford. After receiving a degree in 1942 in politics, philosophy and economics, she briefly worked as an economist for the British Government. Besides this, she spent her life at Oxford as a lecturer, tutor, and fellow, interspersed with visiting professorships to various American colleges, including Cornell, MIT, City University of New York and University of California Los Angeles.

Virtue ethics

In the philosophical world, Philippa Foot is best known for her work repopularising virtue ethics in the 20th century. Virtue ethics defines good actions as ones that embody virtuous character traits, like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. This is distinct from deontological ethical theories which encourage us to think about the action itself and its consequences or purpose instead of the kind of person who is doing the action.

“What I believe is that there are a whole set of concepts that apply to living things and only to living things, considered in their own right. These would include, for instance, function, welfare, flourishing, interests, the good of something. And I think that all these concepts are a cluster. They belong together.”

The doctrine of double effect

Imagine you are the driver of a runaway trolley that is barrelling down the tracks. You have the option to do nothing, and let five people die, or the option to switch the tracks and kill one person.

This is Philippa Foot’s famous trolley problem. This thought experiment encourages us to think about the moral differences between actively causing death (e.g. pulling a lever to get the trolley to change tracks) and passively or indirectly causing death (doing nothing, allowing the trolley to kill five people). Utilitarians might argue that five deaths is far less desirable than one death, but many people instinctively feel that actively causing a death has a different moral weight than doing nothing.

Perhaps Foot’s most influential paper is The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect, published in 1967. Here, she explains what is called the Doctrine of the Double Effect, which explains why some very bad actions (like killing) might be permissible because of their potentially positive outcomes. The trolley problem is one example of the doctrine of double effect, but she also uses various other cases.

“The words “double effect” refer to the two effects that an action may produce: the one aimed at, and the one foreseen but in no way desired. By “the doctrine of the double effect” I mean the thesis that it is sometimes permissible to bring about by oblique intention what one may not directly intend.”

For example, what if one person needed a large dose of a rare medicine to save their life, but that same amount of medicine could save the lives of five others who each needed less? Would we think that the “oblique intention” of a nurse who administers the medicine to one person instead of the five people is justified?

Foot finds that it would be wise to save the five people by giving them each a one-fifth dose of the medicine. However, she encourages us to interrogate why this feels different from the organ donor case, where we save five people who need organ transplants by sacrificing one person.

“My conclusion is that the distinction between direct and oblique intention plays only a quite subsidiary role in determining what we say in these cases, while the distinction between avoiding injury and bringing aid is very important indeed.”

When the trolley problem is taken to its logical conclusion, these fallacies become even more obvious. As John Hacker-Wright writes, the trolley problem “raises the question of why it seems permissible to steer a trolley aimed at five people toward one person while it seems impermissible to do something such as killing one healthy man to use his organs to save five people who will otherwise die.”

Foot has also contributed to moral philosophy with her writing on determinism and free will, reasons for action, goodness and choice, and discussions of moral beliefs and moral arguments.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We are pitching for your pledge

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JAN 2024

Professionally a poet, professor and philosopher, Audre Lorde (1934-1992) also proudly carried the titles of intersectional feminist, civil rights activist, mother, socialist, “Black, lesbian [and] warrior.” She is also the woman behind the popular manifesto “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde in New York City, to Frederic and Linda Belmar Lorde, on the 18th of February 1934, Lorde fell in love with poetry as a form of expression at a young age.

“I used to communicate through poetry,” she recalled in conversation with Claudia Tate for Black Women Writers at Work. “When I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry,” she said. Lorde was thirteen.

Alongside her education at Hunter High School in New York, and working on the school’s literary magazine, she published her first piece of literature in the 1951 April issue of Seventeen Magazine. She earned a Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College in 1959, preceding a master’s degree in library science in 1961 from Columbia University. Following that, Lorde worked as a librarian for public schools in New York City from 1961 to 1968, working her way to head librarian of Manhattan’s Town School. In 1980, Lorde and her friend, a fellow writer and activist, created a publishing house, ‘Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.’ Throughout these years, Lorde was prolific and wrote some of her most recognised volumes of poetry. A full discography of her work can be found at the end of this article.

Authorship and legacy

Expression of self and personal philosophy through literature became a cornerstone of Audre Lorde’s life and one of her greatest contributions to the discourse on discrimination and equality today.

A proud feminist, Lorde’s authorship strived to offer an authentic depiction of the female experience; the good, the bad and the complex. She felt academic discourse on feminism was white and heterosexual centric, lacking consideration of the lived realities of Black and queer women. Thus, she put the stories of these women at the centre of her literature.

Lorde’s philosophy focussed particularly on intersectional discrimination and academic discourse’s inability to accommodate it. She revered differences amongst humans, arguing true equality can only be achieved through celebrating rather than homogenising our different identities.

Third Wave Feminism

Lorde was a prominent member of the women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights movements during the second wave of feminism. As a woman with many of her own labels, Lorde used her lived experience and literary expertise to shine a light on the experience and voices of other women with multiple signifiers. She implored society to confront racist feminism, the nuances of the Black female experience and the cognitive dissonance between educating yourself on feminism whilst not bearing witness to the experiences of all women, – particularly women of colour whose intellectual labour and contributions to such academia have been so routinely overlooked. Thus, helping kickstart the third wave of feminism, also spearheaded by another big thinker, Kimberle Crenshaw.

Through her words, Lorde aimed to acknowledge and capture the pain as well as the joy she felt as an openly queer Black woman. This bare-all intent and celebration of individuality is particularly felt in her work, The Cancer Journals and her subsequent public encouragement of other breast cancer survivors to wear their mastectomies on their chest, rather than accept prosthesis purely for aesthetic motivations. “It is that very difference that I wish to affirm… I lived it, I survived it, and wish to share that strength with other women.”

Philosophy on difference

Lorde was an advocate for difference amongst human beings. For her, difference was the key to eradicating discrimination and moving forward in unity. As we constantly reevaluate what it means to be human, what we hold dear and the ethical pillars we lean on to guide us, Lorde philosophised that it was vital we harness rather than fear that which separates us from our friends, peers and enemies. Rather than homogenising humanity, the future of equality relies on our ability to relate across differences. Finding community is not about conforming, it is about accepting. It must be an act of opening up, not of shutting down.

Lorde examined difference particularly through an intersectional feminist lens. Identifying and subverting the conditioning of women to view their differences as causes for separation and self-judgement.

What we need first, however, is courage. To have our beliefs and perspectives stretched and challenged as we begin the journey of embracing that which makes us different from those around us.

Intersectionality

Lorde was acutely aware of and vocal about the pressure on marginalised people to divide their identities in order to fight for recognition of their discrimination. Academia was constructed to examine, debate and interrogate ways of being. At the time, it was established by white men, and thus contributions to this school of thought were limited to the lived realities and perspectives of these men. As a result, the notion of a human norm came about, and this norm was white, male, heterosexual and often, but not always, wealthy, educated and upper class. Every deviation from this ideal was considered a handicap and treated as such.

In her speech at the New York University Institute for the Humanities, where she debuted her admonishment: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” Lorde cautioned people of colour and other marginalised demographics against the pressure to conform to the limited criteria of ‘acceptable’ laid out by discrimination discourse in white academia, in order to have their needs met. She argued fighting for equality within a system with the notion of a human ideal will only lead to disappointment. True and deeply entrenched equality can only happen through an entire paradigm shift; the unravelling of a human norm in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Anarchy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Karl Marx

Karl Marx (1818-1883) was a philosopher, economist, and revolutionary thinker whose criticisms of capitalism and breakdowns of class struggle continue to influence contemporary thought about economic inequality and the worth of individual labour.

He was not only a prominent figure in the world of philosophy but also a key player in economic and political theory. Marx’s life and work were deeply intertwined with the tumultuous historical backdrop of the 19th century, marked by the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism.

Born in Trier, Prussia (now in Germany), Marx began with a focus on law and philosophy at the University of Bonn and later at the University of Berlin. During his time in Berlin, he encountered the ideas of G.W.F. Hegel, whose methods significantly influenced Marx’s own philosophical approach.

In collaboration with Friedrich Engels, Marx developed and refined his ideas, culminating in some of the most influential works in the history of political philosophy. For example, his infamous The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867, 1885, 1894).

Historical materialism and class struggle

One of Marx’s central ideas was historical materialism, a theory that analyses the evolution of societies through the lens of economic systems. According to Marx, the structure of a society is primarily determined by its mode of production: the ways commodities and services are produced and distributed, and the social relations that affect these functions. In capitalist societies, the means of production are privately owned, leading to a class-based social structure separating the owners and the workers.

Marx’s analysis of class struggle underscores the ethical imperative of addressing economic inequality. He argued that under capitalism, the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) exploit the proletariat (the working class) for their own profit. This exploitation, he claims, is the engine that drives the capitalist system, where workers are paid less than the value of their labour while the bourgeoisie reap the profits. This exploitation also results in alienation, where workers are estranged from the full effects of their labour and, Marx argues, even from their own humanity.

Marx’s arguments call for a reevaluation of the inherent fairness of such a system. He questions the morality of a society where wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a few while the masses toil in poverty. This is an ethical challenge that continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about income inequality and social justice.

Marx’s critique challenges us to consider whether a society that values profit and efficiency over the well-being and fulfillment of its members is ethically justifiable.

To address this concern, Marx envisioned a classless society, where the means of production would be collectively owned. This transition, he believed, would eliminate the inherent exploitation of capitalism and lead to a more just and equitable society. While the practical realisation of this vision has proven challenging, it remains a foundational ethical ideal for some, emphasising the need to confront economic disparities for the sake of human dignity and fairness.

Critique of capitalism and commodification

Marx’s critique of capitalism extended beyond its class divisions. He also examined the profound impact of capitalism on human relationships and the commodification of virtually everything, including labour, under this system. For Marx, capitalism reduced individuals to mere commodities, bought and sold in the labour market.

Marx’s critique of commodification highlights the importance of valuing individuals beyond their economic contributions. He argued that in a capitalist society, individuals are often reduced to their economic worth, which can erode their sense of self-worth and dignity. Addressing this ethical concern calls for recognising the intrinsic value of every person and fostering functions in societies that prioritise human well-being over profit.

The communist vision

Marx’s ultimate vision was communism, a classless society where resources would be shared collectively. In such a society, the state as we know it would wither away, and individuals would contribute to the common good according to their abilities and receive according to their needs.

This communist vision raises questions about the ethics of property and ownership. It challenges us to rethink the distribution of resources in society and consider alternative models that prioritise equity and communal well-being. While achieving a truly communist society might be complex or even out of reach, the aspiration of creating a world where everyone’s needs are met and individuals contribute to the best of their abilities is still a general ethical ideal many people intuitively strive for.

Despite this, Marx’s ideas have faced much criticism. Many believe that a classless society with a centralised power risks authoritarianism, Marx’s economic planning lacked detail, communism goes against human nature of self-interest and competition, and historical and contemporary communist systems face large practical challenges.

In spite of, and sometimes because of, these challenges, Marx’s ideas continue to spark ethical discussions about economic inequality, commodification, and the nature of human relationships in contemporary society. His legacy serves as a reminder of the enduring importance of grappling with questions of justice, equality, and human dignity in our ever-evolving social and economic landscapes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Economic reform must start with ethics

READ

Business + Leadership

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JUL 2023

Judith Jarvis Thomson (1929-2020) is one of the most influential ethicists and metaphysicians of the 20th century. She’s known for changing the conversation around abortion, as well as modernising what we now know as the trolley problem.

Thomson was born in New York City on October 4th, 1929. Her mother was Catholic of Czech heritage and her father was Jewish, who both met at a socialist summer camp. While her parents were religious, they didn’t impose their beliefs on her.

At the age of 14, Thomson converted to Judaism, after her mother died and her father remarried a Jewish woman two years later. As an adult, she wasn’t particularly religious but she did describe herself publicly as “feel[ing] concern for Israel and for the future of the Jewish people.”

In 1950, Thomson graduated from Barnard College with a Bachelor of Arts (BA), majoring in philosophy, and then received a second BA in philosophy from Cambridge University in England in 1952. She then went on to receive her Masters in philosophy from Cambridge in 1956 and her PhD in philosophy from Columbia University in New York in 1959.

Violinists, trolleys and philosophical work

Even though she had received her PhD from Columbia, the philosophy department wouldn’t keep her as a professor as they didn’t hire women. In 1962, she began working as an assistant professor at Barnard college, though she later moved to Boston University and then MIT with her husband, James Thomson, for the majority of her career.

Thomson is most famous for her thought experiments, especially the violinist case and the trolley problem. In 1971, Thomson published her book A Defense of Abortion, which presented a new kind of argument for why abortions are permissible during a time of heightened debate in the US as a result of the second wave feminist movement. Arguments that defended a woman’s right to an abortion circulated feminist publications and eventually led to the Supreme Court ruling in favour of Roe v. Wade (1973).

“Opponents of abortion commonly spend most of their time establishing that the foetus is a person, and hardly any time explaining the step from there to the impermissibility of abortion.” – Judith Jarvis Thomson

The famous violinist case asks us to imagine if it is permissible to “unplug” ourselves from a famous violinist, even if it is only for nine months and being plugged in is the only thing keeping them alive. As Thomas Nagel said, “she expresses very clearly the essentially negative character of the right to life, which is that it’s a right not to be killed unjustly, and not a right to be provided with everything necessary for life.” To this day, the violinist case is taught in classrooms and recognised as one of the most influential thought experiments arguing for the permissibility of abortion.

Thomson is famous for another famous thought experiment, the trolley problem. In her 1976 paper “Killing, Letting Die and the Trolley Problem,” Judith Jarvis Thomson articulates a famous thought experiment, first imagined by Philippa Foot, that encourages us to think about the moral relevance of killing people, as opposed to letting people die by doing nothing to save them.

In the trolley problem thought experiment, a runaway trolley will kill five innocent people unless someone pulls a lever. If the lever is pulled, the trolley will divert onto a different track and only one person will die. As an extension to Foot’s argument, Thomson asks us to think if there is something different about pushing a large man off a bridge, thereby killing him, to prevent five people from dying from the runaway trolley. Why does it feel different to pull a lever rather than push a person? Both have the same potential outcomes and distinguish between killing a person and letting a person die.

In the end, what Thomson finds is that oftentimes, the action as well as the outcome are morally relevant in our decision making process.

Legacy

Thomson’s extensive philosophical career hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2012, she was awarded the American Philosophical Association’s prestigious Quinn Prize for her “service to philosophy and philosophers.” In 2015, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Cambridge, and then in 2016 she was awarded another honorary doctorate from Harvard.

Thomson continues to inspire women in philosophy. As one of her colleagues, Sally Haslanger, says: “she entered the field when only a tiny number of women even considered pursuing a career in philosophy and proved beyond doubt that a woman could meet the highest standards of philosophical excellence … She is the atomic ice-breaker for women in philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Big thinkerClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 APR 2023

Committed to individualism and credited as the father of transcendentalism, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher and poet.

Initially on a path to follow his father’s footsteps and serve in the Christian ministry, Emerson attended Harvard’s Divinity School to become a pastor. But as time went on and he delved deeper into his religious studies, he realised an unignorable sense of detachment and divergence from the traditional religious values he was immersed in. And so he left the Second Unitarian Church and decided to forge his own path.

“To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.”

Emerson’s influential career began with public lectures in Boston that would inspire some of his most renowned essays and ideas. His lectures centred on human culture, English literature, biography and philosophy. He was known for popularising the major movement known as transcendentalism.

The Father of Transcendentalism

“Transcendental” was initially coined by philosopher Immanuel Kant in his theory of transcendental idealism. It’s a theory of perception that holds space and time, along with our five senses, are all subjective experiences and don’t exist outside of the human experience.

Even though Kant coined the term, Emerson is regarded as the father of transcendentalism.

Emerson’s transcendentalism, which became one of America’s first literature and philosophical movements, holds that we ought to be doubtful of knowledge we get from our five senses or even logic and reason; the only trustworthy source of knowledge manifests itself in our personal intuition and self-revelations.

In one of his first lectures, “The Uses of Natural History”, Emerson planted the initial seed for the movement when he explained science as something innately human. He emphasised nature to be an extension of one’s self: “the whole of Nature is a metaphor or image of the human mind.”

His book-length 1836 essay “Nature” is what officially and explicitly defined transcendentalism.

In essence, transcendentalists believe nature is paramount: all their ideals are rooted in the natural world. They believe all things are inherently good, humans and nature alike. In much the same way, transcendentalists see the divinity – the “God” – in everything and everyone. As Emerson wrote, “I am part or particle of God.” Transcendentalists also believe in the human potential for achieving greatness and genius.

Emerson is responsible for introducing a number of people to metaphysical concepts for the first time. A group he helped found in the late 1830’s called the Transcendental Club had dangerous conversations that critiqued societal institutions of the time, such as organised religion and slavery. Its members included prominent thinkers of the time, like Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller, and allowed a space for transcendentalist ideas to grow.

Self-Reliance

As the title of one of his most famous essays, “Self-Reliance” describes one of his principal philosophies: relying solely on ourselves. Emerson’s transcendentalism has been equated to romantic individualism because of his emphasis on the self. For understanding and greatness, Emerson believed we ought only to rely on ourselves and trust our intuition. In fact, he believed the only thing separating the common person from “greatness” is that the “greats” have the gall to admit precisely what they’re feeling when they feel it. As humans, much of our experiences and emotions are shared, and Emerson saw beauty in such commonalities.

At the same time, he cited conformity as a major barrier to achieving greatness. He thought we should be comfortable and proud of being distinctly ourselves. He praised individuality and the pursuit of achieving “an original relation to the universe” by tuning inwards.

The key to unlocking genius is listening to what Emerson called our “creative insight”. He felt such insight was decidedly divine, God’s way of individually speaking to us. This insight is necessary for anyone to accomplish anything meaningful, and so Emerson encouraged everyone to trust their own creative insight over societal ones. Listening to our divinity, our creative insight, yields a life lived authentically.

“It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

It’s these transcendentalist ideologies that would eventually inspire philosopher Henry David Thoreau to reject society and go into the woods in order “to live deliberately and front only the essential facts of life”. And that same line of thinking is what inspired Christopher McCandless, an infamous American adventurer, to abandon family and escape to Fairbanks, Alaska in the 1990s. His story of living in the solitude of wilderness was later popularised in the film and novel Into the Wild.

Although some find wisdom and beauty in Emerson’s fierce admiration of solitude and complete rejection of groupthink, others see privilege in his ideals. Not everyone is able to exercise free will; not everyone can afford to stray from the norm and escape their social circumstances. And so to some, his ideas are lofty and unattainable, less you have the power of class and money on your side.

Beyond privilege, others see selfishness in his philosophies. By tuning inwards and considering only our own needs and desires, what is lost? What might we sacrifice when we neglect those around us? When we disregard even our loved ones? And yet, Emerson never said anything definitively:

“But it is the fault of our own rhetoric that we cannot strongly state one fact without seeming to belie some other. I hold our actual knowledge is very cheap.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships